One of the most controversial decisions in Supreme Court history was caused by aftershocks of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, and it’s still being debated today.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese military forces attacked the United States base in Hawaii without warning. More than 2,000 Americans died in the attack, and a united Congress answered President Franklin Roosevelt’s request for war.

On December 7, 1941, Japanese military forces attacked the United States base in Hawaii without warning. More than 2,000 Americans died in the attack, and a united Congress answered President Franklin Roosevelt’s request for war.

In early 1942, President Roosevelt issued Presidential Executive Order 9066, after fears generated by the Japanese attack made the safety of America's West Coast a priority.

The order started a process that gave the military power to exclude citizens of Japanese ancestry from regions called “military areas.”

Under another provision, called Exclusion Order No. 34, a Japanese-American citizen named Fred Toyosaburo Korematsu was arrested for going into hiding in Northern California after refusing to go to an internment camp.

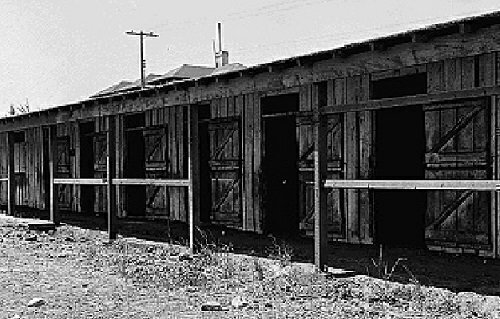

There were 10 camps set up nationally, and about 120,000 people were interned in the camps during the war. About two-thirds of them were Japanese-Americans who were born in the United States.

Korematsu appealed his conviction through the legal system, and the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case in late 1944. The court had heard a similar case in 1943, Hirabayashi v. United States, and decided that Gordon Hirabayashi, a college student, was guilty of violating a curfew order.

The Korematsu v. U.S. case in 1944 decision referenced the Hirabayashi case, but it also ruled on the ability of the military, in times of war, to exclude and intern minority groups.

The court ruled by a 6 to 3 vote that the government had the power to arrest and intern Korematsu. Justice Hugo Black, writing for the majority, included a paragraph that is still debated today:

“It should be noted, to begin with, that all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect. That is not to say that all such restrictions are unconstitutional. It is to say that courts must subject them to the most rigid scrutiny. Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can,” Black said.

Later in the decision, Black argued the necessity of the military’s decision.

“Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire, because the properly constituted military authorities feared an invasion of our West Coast and felt constrained to take proper security measures, because they decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast temporarily,” he said.

In subsequent years, the American internment policy has been met with harsh criticism.

One 1948 law provided reimbursement for property losses incurred by interned Japanese-Americans. In 1988, Congress awarded restitution payments of $20,000 to each survivor of the 10 camps.

As part of the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, Congress apologized "on behalf of the people of the United States for the evacuation, relocation, and internment of such citizens and permanent resident aliens."

President Bill Clinton awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to Korematsu in 1998, and President Barack Obama bestowed the same honor on Hirabayashi in 2012. During the 1999 ceremony, Clinton said, "In the long history of our country's constant search for justice, some names of ordinary citizens stand for millions of souls--Plessy, Brown, Parks. To that distinguished list today we add the name of Fred Korematsu."

President Obama has awarded the medal posthumously to Hirabayashi. Federal courts also overturned the original convictions of Hirabayashi and Korematsu.