By Eric L. Muller

The story of the United States Constitution is the story of ordinary people. That may be the most important message in today’s Constitution Day panel discussion at the National Constitution Center featuring John Tinker, Karen Korematsu, and Cheryl Brown Henderson.

There’s no doubt that hugely important legal principles emerged from John Tinker’s decision to wear a protest armband in school and Cheryl Brown Henderson’s quest to attend a racially integrated school and Karen Korematsu’s father Fred’s decision not to comply with the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Those principles deserve careful discussion. Students of constitutional law parse the words and reasoning in the Supreme Court’s Tinker, Brown, and Korematsu opinions in high schools, colleges, and law schools across the country. This is how it should be.

There’s no doubt that hugely important legal principles emerged from John Tinker’s decision to wear a protest armband in school and Cheryl Brown Henderson’s quest to attend a racially integrated school and Karen Korematsu’s father Fred’s decision not to comply with the mass removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. Those principles deserve careful discussion. Students of constitutional law parse the words and reasoning in the Supreme Court’s Tinker, Brown, and Korematsu opinions in high schools, colleges, and law schools across the country. This is how it should be.

But underlying the intricacies of these legal doctrines are human stories – of what it feels like to have your ideas censored, or to be barred from a school because of the color of your skin, or to be forced from your home because of your parents’ nationality. Constitutional cases emerge from conditions – the circumstances in which people find themselves as a result of actions by their government. So if you really want to understand the cases, you need to understand the conditions. And the people.

I’ve just launched a podcast that does just this. I call it “Scapegoat Cities.” Each roughly 15-minute episode tells one true story of the experiences of a Japanese American in the WWII camps that everyone from the inmates all the way up to FDR called “concentration camps.” These are not stories of great legal cases; they are stories about what ordinary people – the Fred Korematsus of the world – endured between 1942 and 1945.

These are not well-known stories even among those who study this time period. For more than twenty years I have done research for my books and articles by travelling around the country digging in the 75-year-old archival records of little-studied government agencies. Every now and then I have come across a gem of a story – a touching, long-forgotten narrative that captures some aspect of Japanese Americans’ incarceration experiences. They are stories of sadness and loss, of indignation and conflict, of resilience and even of moments of love and joy.

The first three episodes are now available, and they give a good idea of the sorts of experiences the podcast documents. “The Desert Was His Home” tells the story of Otomatsu Wada, an elderly Japanese widower whose life crumbles when he is forced from his home and his farming business on the coast and moved to a camp in the desert of southern Arizona. When his son, his only relative in camp with him, gets a furlough to go pick beets in Montana, Mr. Wada announces that he is going to leave camp to follow him. Nobody pays him any mind until the day in May of 1943 – a 103-degree day – when he goes missing.

In “Slip Slidin’ Away,” Japanese American boys from Los Angeles go for a playful romp in the Wyoming snow in November of 1942, sledding with makeshift sleds down a hill at the edge of the concentration camp. That playful romp suddenly turns into a sobering lesson about control and confinement.

And “The Irrepressible Moe Yonemura” tells of an extraordinary and upbeat young Japanese American man who defies the racism of his day by becoming one of the most popular and well-known members of his class at UCLA. He misses his graduation in 1942 because he has been locked up in a camp, but nothing can stop him from leading and inspiring his fellow prisoners during their months and years of captivity. In 1943, when the Army allows young men to volunteer from behind barbed wire into a segregated Army unit, Moe Yonemura is among the first to go, eager to demonstrate the patriotism of his generation of Japanese Americans. With his family still imprisoned in a concentration camp, Moe fights – and dies – for someone else’s freedom.

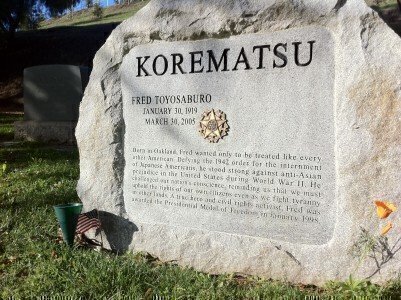

Fred Korematsu has a fascinating personal story as well, one that is better known because he took a challenge to removal and imprisonment all the way to the Supreme Court. His act of resistance is a deeply human story as well. The young man resisted government orders to show up for removal not just because he thought it was wrong, but because he wanted to stay in California with the young Caucasian woman with whom he was in love. It was human emotion – and not just constitutional principle – that led Fred Korematsu to do what he did.

It is all too easy, when we study constitutional cases and debate government policies, to think of them as intellectual exercises. They are that, but they are also much more than that. Understanding the human costs of government policies can help us gain a richer, fuller, and more passionate commitment to protecting constitutional values.

You can subscribe to “Scapegoat Cities” on Apple Podcasts, Google Play, Stitcher, and many other podcast sites, and is free to download. You can also find the episodes, along with photographs and other background materials, on the podcast’s own website.

Eric L. Muller is the Dan K. Moore Distinguished Professor at the UNC School of Law. He is a nationally recognized expert on the wartime removal and imprisonment of Japanese Americans. His books on the subject include "Free to Die for their Country: The Story of the Japanese American Draft Resisters in World War II" (University of Chicago Press) and "Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II" (University of North Carolina Press). He was also the curator of the permanent historical exhibit at the Heart Mountain Interpretive Center in northwest Wyoming, the site of one of the ten Japanese American concentration camps run by the US government between 1942 and 1945.