On this day in 1947, Congress changed the order of who can succeed the President and Vice President in office, more closely reflecting the ideas of the Founding Fathers.

When the Constitution was written in 1787, the issue of who was to take the President’s place in case of death, disability or resignation was murky at best. It took until 1841 for John Tyler, the first Vice President to face the problem and settle the question—at least until the 25th Amendment was ratified in 1967 and did so officially.

After William Henry Harrison died just a month after his own inauguration in April 1841, Tyler decided to take the oath to become President – and not to simply become the “Acting President” as some people suggested. The “Tyler precedent” held for eight instances until the 25th Amendment was ratified and confirmed that the Vice President indeed becomes President upon a sitting President’s death or removal from office.

But what happens when the offices of President and Vice President are vacant at the same time and no one can “discharge the powers and duties of the office of President?” Responsibility for deciding the line of succession was left to the First Congress. In 1791, a House committee suggested that Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, an anti-Federalist, be named as third-in-line to the White House, an idea opposed by the Federalists.

Instead, the Second Congress agreed in 1792 that the Senate President Pro Tempore, (the Senate president in the absence of the vice president,) followed by the Speaker of the House, would serve as Acting President until a disability was removed that prevented a President or Vice President from serving, or until a new election was held. (In that case in 1792, Richard Henry Lee and Jonathan Trumbull were next in line as Acting President.)

The original Presidential Succession Act had some problems, specifically related to the Constitution’s missing provision to name a replacement Vice President for when that office became vacant. (The 25th Amendment would later address that problem.)

In 1886, Congress and the Grover Cleveland administration pressed for changes in the Succession Act after Cleveland’s Vice President, Thomas Hendricks, had died. Nervous that Democrats would lose power in the case of President Cleveland’s death, they fought to give Cabinet members the line of succession. The 1886 plan made the Secretary of State third-in-line, and then other Cabinet members based on the tenure of their departments. Importantly, a special election wasn’t required to choose a new President.

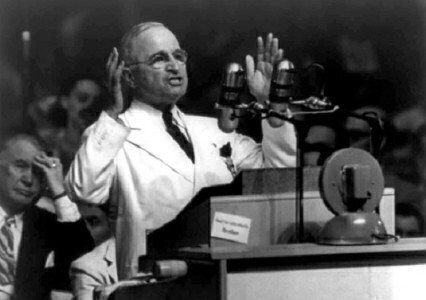

After Franklin Roosevelt’s death in 1945, Harry Truman took office. Once President, he pressed for a return to the succession line from the 1792 act with one important difference: The House Speaker would be the third-in-line for the White House, followed by the Senate President Pro Tempore, thus flipping the order. Congress passed a revised version of this plan, which was signed by Truman and enacted on July 18, 1947. There would be no special election provision, and Cabinet officers, based on their department’s tenure, followed the House Speaker and the Senate President Pro Tempore in the line of succession. Anyone serving in the role of Acting President needed to resign the office they held that allowed them to serve as Acting President.