The date of September 13, 1788 isn’t celebrated as a major anniversary in American history, but it was a big day in the creation of our current form of constitutional government.

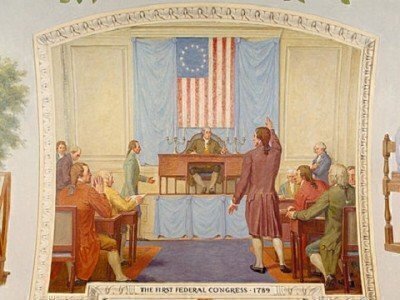

On that Saturday, the Congress of the Confederation set the dates for the election of a President and the transition to a Congress under the new Constitution – effectively agreeing to shut itself down as a legislative body in March 1789.

In its official Election Ordinance, the Confederation Congress acknowledged that all the requirements for the transition to a new form of government had been met: The Constitution had been written in Philadelphia in September 1787, later ratified by the required number of states in June 1788, and the ratification documents were authenticated and filed.

The ordinance spelled out that electors for the presidential election would be appointed on the first Wednesday of January 1789; the electors would assemble a month later to choose a President; and that “the first Wednesday in March next be the time and the present seat of Congress the place for commencing proceedings under the said Constitution.”

The ordinance also cleared the way for Senators and Representatives to be elected within states to serve in the new Congress. Three weeks later, Pennsylvania became the first state to name its two Senators: bitter rivals Robert Morris and William Maclay.

It also didn’t specifically name New York City as the national capital, instead stating that the then-current location of Congress (which happened to be New York) would be the starting place of the new government under the Constitution.

Article I, Section 8 of the new Constitution granted Congress powers to decide on the location of a federal district to serve as the capital. “Such District (not exceeding ten Miles square) as may, by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States,” it read.

The Confederation Congress had been arguing for months about where to locate a temporary national capital. One faction favored New York, while another wanted Philadelphia, the site of the Constitutional Convention. Baltimore, Annapolis, and Lancaster were also proposed as sites.

The ordinance was a short-term solution to the capital issue. Pennsylvania’s delegates wrote to Thomas Mifflin, the state assembly speaker, about why they agreed to the compromise. “The organization of the new government could no longer be suspended without risking consequences more disagreeable,” they said, noting that Pennsylvania lacked enough votes to obtain the capital.

The Compromise of 1790 would settle the issue of the federal district’s location, with an agreement reached among Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton to promote the capital’s location in Maryland and Virginia—now Washington, D.C.—in exchange for the assumption of state debt by the new federal government.

The Residence Act of 1790 allowed President George Washington to pick the federal district’s location, and in another compromise brokered by Hamilton and Robert Morris, Philadelphia would serve as the temporary capital for 10 years, until the permanent federal district on the Potomac was ready.