It was on this day that the United States Senate began the first trial of a sitting United States President after the House approved impeachment charges against President Andrew Johnson.

Johnson became President in 1865 after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination. A former Democrat who ran as a candidate alongside Lincoln in 1864, President Johnson’s relationship with the Republican leadership quickly crumbled. A faction called the Radical Republicans, led by Thaddeus Stevens and Charles Sumner, dominated the party and saw President Johnson as obstructing its goals during the period of Reconstruction.

On February 24, 1868, President Johnson was impeached by the House of Representatives. The House charged Johnson with violating the Tenure of Office Act and other acts. The alleged violations stemmed from Johnson’s decision to remove Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a prominent Radical Republican left over from the Lincoln Cabinet. To block Johnson from removing Cabinet members without its approval, the House passed the Tenure of Office Act in 1867.

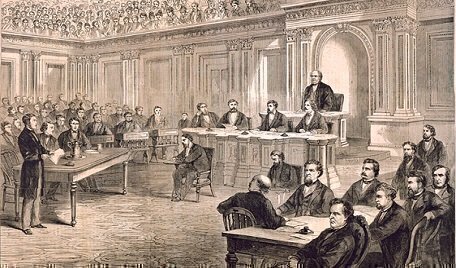

Two-thirds of the Senate would be needed to convict Johnson, and the Republican Party made up more than two-thirds of the Senate. In all, Johnson faced 11 articles of impeachment. The Senate had met since early March to agree on the rules for the trial and its administrator, Chief Justice Salmon Chase. On March 5, the trial proceedings officially began as Chief Justice Chase convened the Senate as a trial court under oath.

Then on March 13, the Senate compelled the President, or his representatives, to appear in person. At 1:10 p.m., Chief Justice Chase swore in the House managers for the trial, including Thaddeus Stevens (who at this point, was mortally ill and had to be carried by two younger men in a chair to the Senate from the House) and the father of the 14th Amendment, John Bingham.

Chase asked the Senate sergeant at arms to call for the President to face the trial bar. “In a loud voice, and amid the stillness of the whole chamber, he called three times, ‘Andrew Johnson, Andrew Johnson, Andrew Johnson!’ There were hundreds among that intelligent audience, who bent forward and eagerly strained their eyes, expecting the President to appear in response to that stentorian behest,” the New York Times said.

Instead, President Johnson’s chief critic in the House, Benjamin Butler, strolled onto the Senate floor at an inopportune moment to the public gallery’s amusement. But soon after, the President’s formidable legal team appeared, including Henry Stanbery (who had resigned the day before as Attorney General) and former Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Curtis. On the advice of his attorneys, President Johnson would not be appearing at the trial.

Once other members of the House were seated, the trial’s first motion was made. Stanbery asked for a 40-day delay so Johnson’s legal team could prepare a proper defense. Bingham immediately objected, leading to former Supreme Court Justice Curtis to remark that “it was contrary to custom in all other cases to compel an accused person to open his case when he pleads to the indictments.”

Three hours later, the matter was decided by a Senate vote. “The Chief Justice, in his calm and polished manner, and in his blandest Supreme Court tones, announced that the motion was overruled,” the Times reported, with arguments set to start on March 23, 1868.

In the end, the trial would last into late May. The first vote on the impeachment articles on May 16 failed by one vote, when Senator Edmund Ross of Kansas cast the deciding tally; he had been expected to vote against Johnson, up until the night before the roll call. A second attempt failed on May 26.