December 2nd is a landmark day in Senate history, marking that chamber’s historic censure of Joseph McCarthy for his conduct during public hearings.

A censure is a public rebuke of a member by the Senate as a body and not the expulsion of a Senator. But a censure vote can have a powerful effect on a Senator’s public image and his or her ability to participate in Senate decisions.

The constitutional precedent for the censure motion comes from Article 1, Section 5, Clause 2, which says that “each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its Members for disorderly behavior, and, with the Concurrence of two thirds, expel a Member.”

However, there is nothing in the Constitution about Congress having the ability to pass a censure motion against a member of another branch of the government. And the word “censure” doesn’t appear in the Constitution.

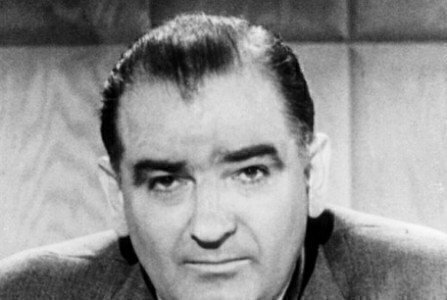

In McCarthy’s case, his political power had gone mostly unchallenged since 1950, when he made a Lincoln Day speech in West Virginia, claiming that Communists had infiltrated the State Department.

“I have in my hand 57 cases of individuals who would appear to be either card-carrying members or certainly loyal to the Communist Party, but who nevertheless are still helping to shape our foreign policy,” McCarthy reportedly said. (There is some dispute about the actual number of alleged Communists he cited in the live speech.)

McCarthy’s controversial remarks found welcoming ears in those early Cold War years. Republican leaders appointed McCarthy as chairman of the Senate Committee on Government Operations in 1953, which included the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

Later that year, McCarthy pressed for hearings on Communist infiltration into the U.S. Army. But in 1954, the Senate Subcommittee on Investigations held its own hearings about accusations exchanged between McCarthy and the Army. The hearings were watched on TV by more than 20 million Americans.

In a dramatic moment, Army counsel Joseph Welch lashed out at McCarthy after the senator refused to produce a list of Communists and instead attacked a young attorney on Welch’s staff who wasn’t at the hearing.

“Senator; you’ve done enough. Have you no sense of decency, sir? At long last, have you left no sense of decency?” Welch said to an ovation from the Senate gallery.

By the summer of 1954, the Senate decided to take action against McCarthy. On July 30, 1954, Ralph Flanders, a Republican, introduced a censure motion that his conduct as chairman of the Senate’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations was “contrary to senatorial traditions.”

McCarthy verbally abused some of his colleagues during hearings that started in August. The Senate then reconvened in a lame-duck session after the November election to consider two charges. And McCarthy again attacked committee members who leveled the challenges. But Republican Arthur Watkins of Utah, who led the selected committee, spoke about how McCarthy violated the Senate’s dignity.

On December 2, 1954, the Senate voted on a motion said that McCarthy “acted contrary to senatorial ethics and tended to bring the Senate into dishonor and disrepute, to obstruct the constitutional processes of the Senate, and to impair its dignity; and such conduct is hereby condemned.” The motion passed by a 67-22 vote.

The effective punishment came against McCarthy in a separate motion, where he lost a key committee chairmanship.

But after December 2nd, McCarthy faded away as a major player in national politics. He died in 1957, by all accounts deeply affected by his rapid fall from power.