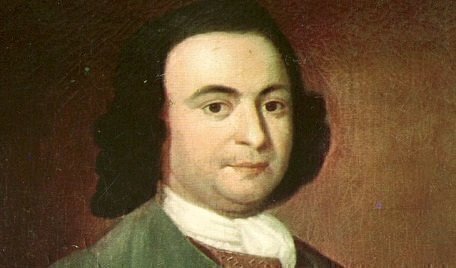

During the 1787 Constitutional Convention, two Georges commanded much attention at Philadelphia: George Washington and his Virginia neighbor, George Mason. In the end, Mason refused to sign the new Constitution, an act that led in part to the Bill of Rights becoming a reality.

Born on December 11, 1725, in Fairfax County, Virginia, Mason belonged to the planter class there and worked with Washington on land issues dating back to the Seven Years’ (or French and Indian) War. Mason also was among the colonists who protested the Stamp Act in 1765, and he had been the driving force behind Virginia’s Declaration of Rights in 1776.

Mason is credited with writing most of that document, which contains some familiar-sounding language. His opening passage soon inspired Thomas Jefferson to add similar language to his Declaration of Independence:

“That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety,” Mason wrote.

Also, other Declaration of Rights sections later became core concepts in a proposed Bill of Rights introduced by James Madison to the First Congress after the Constitution was ratified. For example, Mason wrote that, “That the freedom of the press is one of the great bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic governments,” and that “all men are equally entitled to the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.” Other passages said, “that excessive bail ought not to be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.”

Mason joined Virginia’s legislature, but he refused offers to serve in the Continental Congress, even from Washington. Mason preferred to remain in Virginia and didn’t like public life in general. In 1781, Mason retired from Virginia’s House of Delegates.

However, Mason didn’t turn down a chance to represent Virginia at the 1787 convention in Philadelphia, where he was among the most vocal and respected of delegates. Mason distrusted centralized government and believed a Bill of Rights was essential in order to prevent tyranny and protect states’ rights and individual rights. When it became apparent that the majority of delegates didn’t support a Bill of Rights in the proposed Constitution, Madison noted that Mason said, “that he would sooner chop off his right hand than put it to the Constitution as it now stands.” Mason also believed the proposed Constitution didn’t go far enough to oppose slavery, even though Mason owned slaves.

Mason left the convention without signing the Constitution that would be proposed to the states for ratification. In November 1787, his objections become public when they appeared in a Virginia newspaper.

“There is no Declaration of Rights, and the laws of the general government being paramount to the laws and constitution of the several States, the Declarations of Rights in the separate States are no security,” Mason wrote. “There is no declaration of any kind, for preserving the liberty of the press, or the trial by jury in civil causes; nor against the danger of standing armies in time of peace,” he also added to a long list of complaints.

Back in Virginia, he worked with Patrick Henry to try to defeat his state’s ratification of a document that lacked a Bill of Rights. While that effort failed, there was enough support for a Bill of Rights during the state ratification process in the new nation that Madison led the effort to introduce it in June 1791.

Mason supported much of the new Bill of Rights, which contained elements of his own work from 1776. He wrote to his friend Samuel Griffin that “I have received much Satisfaction from the Amendments to the federal Constitution, which have lately passed the House of Representatives; I hope they will also pass the Senate,” Mason said. Also, Mason wanted amendments that restrained the federal judiciary, modified federal election laws, and removed some executive powers from the Senate. If those changes were made, Mason said, “I could cheerfully put my Hand & Heart to the new Government.”

Suffering from health issues, Mason declined a United States Senate seat and retired again to his residence, Gunston Hall, where he died at the age of 66 in October 1792