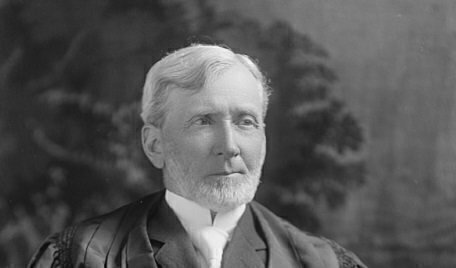

On this day in 1898, Joseph McKenna took his oath and joined the Supreme Court to fill the vacancy of Justice Stephen Field.

President William McKinley had nominated McKenna, his own Attorney General, on January 21, 1898. President Abraham Lincoln had appointed Field to the Court in 1863. Field served for 34 years on the Court before resigning.

President William McKinley had nominated McKenna, his own Attorney General, on January 21, 1898. President Abraham Lincoln had appointed Field to the Court in 1863. Field served for 34 years on the Court before resigning.

The Senate approved McKenna on January 21, 1898 by voice vote. He took his judicial oath on January 26, 1898.

McKenna was born in Philadelphia, but his family moved to California in the mid-1850s. He was admitted to the California bar in 1866 before being elected District Attorney for Solano County six months later at the tender age of 23. After being elected to the House of Representatives as a Republican, McKenna was appointed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals by President Benjamin Harrison in March 1892 until he was appointed Attorney General in January 1897.

McKenna was on the Supreme Court for nearly three decades, resigning in January 1925 after 27 years on the Court. As a result, McKenna’s time on the court corresponded with the period of the Court known as the “Lochner Era.” During this period, in several leading cases, the Court struck down state economic regulations as infringing upon “liberty of contract” under the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Scholars have generally understood McKenna to be a centrist without the same consistent legal philosophies of the two countervailing poles of the Court—the constitutional libertarianism of Justice Rufus Peckham and David Brewer and the minimalism of Justice Oliver Wendall Holmes. McKenna symbolized how the Court during this period usually upheld state labor regulations. As Charles Warren wrote in 1913, “The actual record of the Court thus shows how little chance a litigant has of inducing the Court to restrict the police power of a State, or to overthrow State laws under the ‘due process’ clause.”

He authored 614 majority opinions, and 146 dissenting opinions during his time on the bench. McKenna was not broadly an opponent of regulation, as wrote the unanimous opinion upholding the Pure Food and Drug Act in Hipolite Egg v. U.S. in 1911 and joined the opinion upholding the Mann Act banning “white slavery” or prostitution. However, McKenna also dissented in the 1908 case of Adair v. United States, the case which upheld the right of employers to forbid workers by contract from joining labor unions and struck down the federal law banning these “Yellow Dog” contracts while seven years later, upholding a similar state law in Coppage v. Kansas in 1915.

McKenna joined the Lochner majority, written by Justice Peckham, in 1905 striking down a New York state law limiting bakers to 10-hour work days as an unconstitutional infringement upon the “liberty of contract.” Thereafter, he helped limit the extent of liberty of contract based on gender, joining Brewer’s unanimous opinion in Muller v. Oregon in 1908 upholding ten-hour work days for women working in laundries in Oregon under the premise that women, by virtue of being the weaker gender, did not have the same claims to liberty of contract.

Brewer wrote that, “It is equally well settled that this liberty is not absolute and extending to all contracts, and that a state may, without conflicting with the provisions of the 14th Amendment, restrict in many respects the individual’s power of contract.” McKenna’s biographer, Matthew McDevitt, wrote that the difference between Lochner and Muller was the volume of statistical information presented to the Court showing the physical differences between men and women in the so-called “Brandeis Brief” of Louis Brandeis and his team in favor of the state’s maximum-hours law for women.

McKenna expanded Muller’s ruling in his opinions in the 1914 case of Riley v. Massachusetts, where he upheld a state law limiting the hours of women in factories, saying that, “[n]either the wisdom nor the legality of such means [as chosen by the legislature] can be judged by extreme instances of their operation” to pronounce such operation as arbitrary and unreasonable.” By 1917, in Bunting v. Oregon, McKenna wrote an opinion upholding a state law regulating the hours of all mill, factory, and manufacturing workers. McKenna believed the law regulated hours rather than fixed wages, as it did not explicitly attempt to set a minimum or maximum wage and he could point to the “Brandeis Brief” statistical account of how a ten-hour limit was reasonable.

Six years later in 1923, after the passage of the 19th Amendment giving women the right to vote, McKenna joined Justice George Sutherland’s opinion in Adkins v. Childrens’ Hospital, striking down a minimum wage act for women in the District of Columbia under Lochner. Sutherland’s opinion decided that Muller and Riley no longer applied:

“In view of the great -- not to say revolutionary -- changes which have taken place since that utterance, in the contractual, political and civil status of women, culminating in the Nineteenth Amendment, it is not unreasonable to say that these differences have now come almost, if not quite, to the vanishing point. In this aspect of the matter, while the physical differences must be recognized in appropriate cases, and legislation fixing hours or conditions of work may properly take them into account, we cannot accept the doctrine that women of mature age, sui juris, require or may be subjected to restrictions upon their liberty of contract which could not lawfully be imposed in the case of men under similar circumstances.”

In dissent, Chief Justice William Howard Taft wrote that he believed Bunting had already overruled Lochner. Fourteen years later, in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, the Court would overrule Lochner for good. By the time McKenna retired in January 1925, he had left a record and legacy which remains open to scholarly debate. Was McKenna a judicial moderate or did he represent the incoherency of the Lochner period?

Nicholas Mosvick is a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.