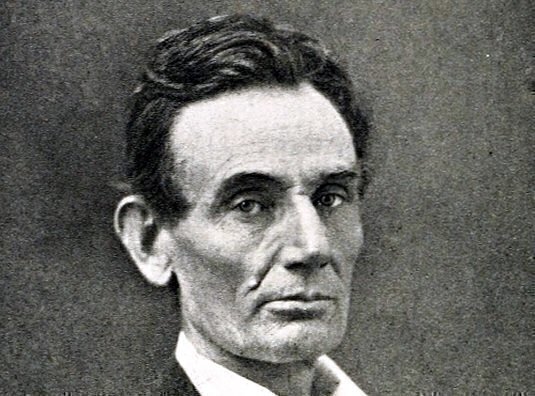

On May 18, 1860, former Congressman Abraham Lincoln upset the Republican front runner, William Seward, at the party’s second convention in Chicago, setting in motion the eventual regional split that became the Civil War.

At that time, the newly formed Republican Party was concentrated in the Northern and Midwestern states, and almost any of its nominees would have attracted a strong negative reaction from the Southern states.

At that time, the newly formed Republican Party was concentrated in the Northern and Midwestern states, and almost any of its nominees would have attracted a strong negative reaction from the Southern states.

Lincoln, however, was a moderate in the GOP and quickly built up a regional reputation after his 1858 debates with Democratic leader Stephen A. Douglas and a stirring speech at New York’s Cooper Union.

The New York Times, which supported Seward, had mute praise for Lincoln the day after his nomination: Lincoln “had a stump canvass [in 1858] with Mr. Douglas in which he was beaten. He is not very strong at the west, but is unassailable in his character.”

A rival newspaper, the New York Tribune, reported that the news wasn’t welcome in Washington, D.C., at the Senate, where Douglas and others had been led to believe Seward was the nominee. Douglas called Lincoln a “gifted” candidate, and the Douglas supporters understood that Lincoln would do much better in the Midwest than other GOP candidates – nullifying Douglas’ strength there.

In the days before the convention, Lincoln was seen as a leading candidate to be the vice president on a ticket with Seward. Lincoln came in second in vice presidential balloting at the 1856 Republican convention in Philadelphia, and it was widely understood that Seward had the most votes heading into the 1860 convention in Chicago.

Unfortunately for Seward, he didn’t have the majority of convention votes for a first ballot win and his limited strength in the North foreshadowed an 1860 presidential loss if he only took the states where he was strongest.

Seward had also offended many Southern states with his prior remarks about ending slavery. In 1858, Seward gave a well-publicized New York campaign speech where he called the regional fight over slavery an “irrepressible conflict” that could only lead to a condition where “the United States must and will … become either entirely a slave-holding nation or entirely a free-labor nation.” By May 1860, he lost support in other factions of the Republican Party when he moved to a more centrist position.

The Lincoln election team, led by future Supreme Court Justice David Davis, lobbied three states hard, Pennsylvania, New Jersey and Indiana, arguing that Lincoln was the best choice to win a national election against a divided Democratic Party.

As the convention opened in a large temporary structure called the Wigman, the Lincoln organizers outmaneuvered the Seward supporters in the hall, and in some cases, got their supporters into the 10,000 seat arena using counterfeit tickets. Davis also assured that Lincoln would be the second choice in states where he didn’t lead Seward, other than the two other candidates: Ohio’s Salmon Chase and Missouri’s Edward Bates.

On the first ballot, Seward led Lincoln by a 173 ½ to 102 margin, with Chase, Bates and Pennsylvania’s Simon Cameron controlling about 150 additional votes, with 233 votes needed for the nomination. But on the second ballot, Cameron and Pennsylvania swung its votes to Lincoln, virtually deadlocking the race between Seward and Lincoln.

As the third ballot started, Lincoln appeared to be just short of the nomination, and his campaigners convinced a handful of Ohio delegates to switch sides, assuring Lincoln’s win. (The Lincoln supporters used promises of patronage without the candidate’s apparent knowledge – Lincoln was back home in Springfield.)

Absent from the convention were representatives of nine southern states, while Virginia had a limited delegation in Chicago (which mostly supported Lincoln).

The New Orleans Picayune, in the Deep South, said that little was known about Lincoln, but it quoted part of his Lincoln’s 1858 Senate nomination speech to show “ an extract from one of his speeches in which the irrepressible conflict of Mr. Seward is avowed in terms hardily less emphatic.”

The quote was, “'A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved -- I do not expect the house to fall -- but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.”

In November 1860, Lincoln won the general election by almost sweeping all the electoral votes in the free states. Douglas took one state in the Midwest.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.