On November 25, 1841, 35 former slaves returned home to West Africa, after a Supreme Court hearing, won by a former United States president, secured their freedom. Former President John Quincy Adams helped convince a southern-dominated court in March 1841 to release the enslaved people in the Amistad case.

Adams and a prominent attorney, Roger Baldwin, agreed to represent the enslaved Africans in a complicated court case that was closely watched nationally. In 1839, Portuguese slave traders in West Africa captured about 500 people and transported them to Havana in Spanish-ruled Cuba. Spanish law prohibited such an act, but the law was mostly ignored in Cuba. Two planters in Havana purchased a group of the West Africans at auction, and using fake documents, planned to transport them to plantations within Cuba.

Adams and a prominent attorney, Roger Baldwin, agreed to represent the enslaved Africans in a complicated court case that was closely watched nationally. In 1839, Portuguese slave traders in West Africa captured about 500 people and transported them to Havana in Spanish-ruled Cuba. Spanish law prohibited such an act, but the law was mostly ignored in Cuba. Two planters in Havana purchased a group of the West Africans at auction, and using fake documents, planned to transport them to plantations within Cuba.

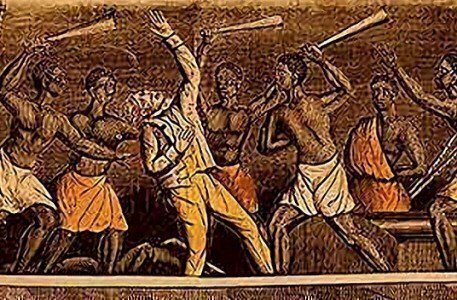

However, the slaves revolted while on the schooner Amistad, killing its captain and cook, and directing the planters to sail the ship to Africa. Instead, the planters steered the ship north, where it wound up at Long Island Sound. The U.S. Navy spotted the vessel and took its occupants into custody.

The American courts were soon confronted with multiple problems, such as the property rights of the planters, the salvage rights for the ship, and if the Africans should be charged with murder – or given their freedom. The U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Connecticut first decided that it didn’t have jurisdiction over an alleged crime committed in international waters. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Smith Thompson, serving as the Circuit Judge, issued that decision.

At a District Court trial in 1840, Baldwin argued that the Africans had been taken illegally by the slave traders. Spain demanded the Africans and the ship returned to that nation under its treaty terms with the United States. President Martin Van Buren had expected the court to rule for the Spanish government in the case. However, Judge Andrew Judson said that the Africans weren’t slaves under Spanish law, and they should be sent to the Van Buren administration to be returned to their homes in Africa under the provisions of federal laws prohibiting the African slave trade in the United States. The Navy crew also was awarded salvage rights for capturing the ship.

The case then quickly made its way to the Supreme Court in Washington. The Van Buren administration believed that the Africans should be sent back to Cuba to honor treaty commitments with Spain. Baldwin argued the earlier court decision was proper, and that the Africans were not slaves under Spanish law. Baldwin also pressed that the Van Buren administration couldn’t represent the claims of a foreign government.

Former President and Secretary of State Adams, then serving in the House of Representatives, agreed to help the Africans plead their case to the Court.

Link: Read Adams' Argument

Pointing to a copy of the Declaration of Independence in the courtroom, Adams said, “I know of no other law that reaches the case of my clients, but the law of Nature and of Nature's God on which our fathers placed our own national existence. The circumstances are so peculiar, that no code or treaty has provided for such a case. That law, in its application to my clients, I trust will be the law on which the case will be decided by this Court.”

He then called out the Van Buren administration. “One of the grievous charges brought against George III was, that he had made laws for sending men beyond seas for trial. That was one of the most odious of those acts of tyranny which occasioned the American revolution. The whole of the reasoning is not applicable to this case, but I submit to your Honors that, if the President has the power to do it in the case of Africans, and send them beyond seas for trial, he could do it by the same authority in the case of American citizens. By a simple order to the marshal of the district, he could just as well seize forty citizens of the United States, on the demand of a foreign minister, and send them beyond seas for trial before a foreign court.”

After a lengthy argument, Adams concluded by reviewing the Court’s honorable tradition since he first appeared before it decades earlier. Days later, in a 7-1 decision, the Court ruled in favor of the captives of the Amistad. Justice Joseph Story wrote the majority decision.

“Upon the merits of the case, then, there does not seem to us to be any ground for doubt, that these negroes ought to be deemed free; and that the Spanish treaty interposes no obstacle to the just assertion of their rights,” Story wrote. While Story called Adams’s remarks “interesting,” he relied more on Baldwin’s statements in his legal reasoning. But Adams’s nine hours of arguments, at the age of 73, clearly had their effect.

The Court ordered the 35 surviving Africans to be freed immediately, and not put under federal custody for eventual transportation back to Africa. Abolitionists raised funds for the freed Amistad captives to be returned to Sierra Leone. On November 25, 1841, the captives set sail on the ship Gentleman for Africa, arriving there in January 1842. Spain continued to ask for compensation until 1860, when Abraham Lincoln became president.