On the 250th anniversary of the Stamp Act, Jonathan Mercantini from Kean University looks at the act fueled American passions about unjustly paying taxes.

That Americans were willing to resist tax increases through political action, lengthy essays, and popular protests should not be surprising to anyone following American politics today. While the authority to levy taxes by Congress and state legislatures has not been disputed since soon after the ratifications of the Constitution, the proper amount, rate, and collection of taxes remains perhaps the most hotly disputed aspect of public policy today. And although history is filled with objections to paying taxes, the uniquely American version of anti-tax protests was born out of the Stamp Act Crisis.

That Americans were willing to resist tax increases through political action, lengthy essays, and popular protests should not be surprising to anyone following American politics today. While the authority to levy taxes by Congress and state legislatures has not been disputed since soon after the ratifications of the Constitution, the proper amount, rate, and collection of taxes remains perhaps the most hotly disputed aspect of public policy today. And although history is filled with objections to paying taxes, the uniquely American version of anti-tax protests was born out of the Stamp Act Crisis.

On March 22, 1765, in the fifth year of his reign, King George III of Britain signed the Stamp Act. The law attracted little notice in London and elsewhere throughout the British Isles. It was a minor revenue measure, designed to raise money to pay for the defense of the North American colonies. King George and the members of Parliament had no inkling that they had given the colonies a strong push toward independence.

The Constitutional questions that emerged in the Stamp Act Crisis were fundamental to governing the colonies and the Empire. Parliament argued that it was the supreme authority in the British Empire and that its power to legislate, including the power to levy taxes, was unlimited. Colonial leaders argued the colonies were not and could not be represented in Parliament. Englishmen could not be taxed without their consent and therefore only the colonial legislatures possessed the power to levy internal taxes in the colonies. The rallying cry was “No Taxation without Representation.” This was not a demand on the part of the colonies to be represented in Parliament. What colonial leaders meant was their belief, long established, of being taxed by their own representatives in their colonial legislatures. Disagreement over these and related constitutional questions were never satisfactorily resolved. The result was the American Revolution.

Great Britain had secured control over much of North America with its victory over France and Spain in the Seven Years’ War (aka the French and Indian War). By electing to keep Canada as the spoils of war, while returning other, arguably more valuable, territories to France, the British government demonstrated that the future of the British Empire lay in North America.

Victory in the war had been momentous, but it had come with a hefty price tag. Britain found itself saddled with an enormous debt. It seemed only natural that Britons on the other side of the Atlantic, who enjoyed a rapidly growing economy and all the benefits of the protection and power of the mighty British Empire, should contribute to their own defense. Trade regulations passed the year before with little fanfare or opposition were designed to make sure that the Empire enjoyed the economic benefits of their colonies. The Stamp Act was another small step toward that goal.

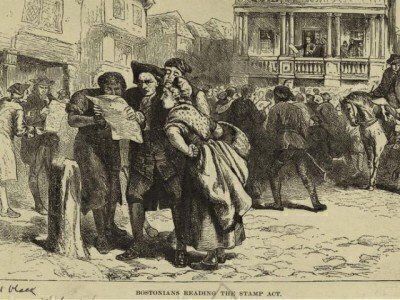

The response in the American colonies, however, was as strong as it was angry. Although they had been alerted to the possibility of a Stamp Tax the year before, the full spectrum of colonists from political leaders to artisans, women, and apprentices were outraged. The tax may have been a minor revenue measure to Parliament, but it represented a massive tax increase on the colonists. Akin to a sales tax today, many everyday items such as newspapers, cards, as well as legal documents, shipping manifests etc. would all be subject to the new tax

Colonial tax policies were quite progressive for the age, with land and property most commonly taxed, which meant that the wealthiest paid most of the taxes. The Stamp Act, however, requiring a tax be paid on many common items like newspapers, playing cards, marriage and apprenticeship papers, would impact much more of the population. The cost of many everyday goods would rise, affecting people of all social classes.

The larger fear was that the Stamp Act was only the first in a series of tax increases on the colonies. The monies to be raised by the Stamp Act were limited. It is always easier, of course, to raise taxes on populations that do not vote for you. This is why governments frequently turn to tax increases on hotel rooms, rental cars and the like. Those services are most often bought, and thus the taxes on them paid, by visitors to that location, not local residents, aka voters.

So, for example, the state of Florida does not have a state income tax because it is able to raise so much money on taxes paid by the tourists who flock to the state. The same pattern was possible in the colonies. Parliament would find it much easier, and less threatening to their political careers, to raise taxes on the colonists who had no way to vote them out of office. Whether or not this was the actual intent of Parliament, its actions gave greater credence to those colonists who feared a conspiracy to deprive them of their liberties had been launched.

The Stamp Act would be repealed the following year having never really taken effect in the colonies. Parliament would search for other ways to tax the colonists who would, in turn, devise boycotts and other means of resisting those efforts. Ultimately, the two sides could not agree on the proper balance of power between colonial and imperial authorities. The result was revolution, independence and a distinct culture of opposing taxes that persists to the present day.

Jonathan Mercantini is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of History at Kean University. He is currently working on a book tentatively titled The Stamp Act Crisis: Taxation, Authority and the American Revolution. He is on Twitter @jmercan