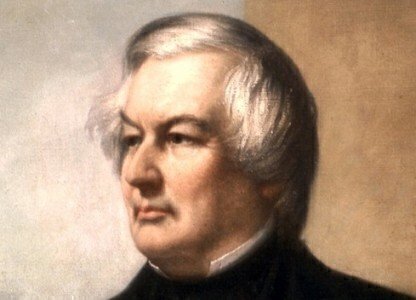

On the occasion of Millard Fillmore's birthday, Constitution Daily looks back at a forgotten President and his role in the crisis that led to the Civil War.

There isn’t that much written about Fillmore, who was relegated to the dust bin of history by his own political party in 1852 after serving less than three years as President. Fillmore ran a second time for the White House on the ticket for the Know Nothing Party in 1856, and then disappeared.

But Fillmore’s place in the national spotlight was brief and it came at a crucial time in the debate over slavery.

Born on January 7, 1800 in Summerhill, N.Y., Fillmore grew up in extreme poverty and lived for a time as a virtual slave when his family allowed him to work as an apprentice to a cloth dresser. Fillmore bought out his commitment to his employer, married his own schoolteacher, and worked his way up through the political system in New York’s Whig Party.

Moving to Buffalo, Fillmore was a protégé of the state Whig party leader, Thurlow Weed, and he served for eight years in the U.S. House of Representatives. Weed convinced Fillmore to resign to run for governor in New York state in 1844. Fillmore lost that election, but he soon won election to the powerful position of New York state comptroller in 1847.

Then, Weed then helped Fillmore get on the 1848 presidential ticket as vice president. Zachary Taylor, the Whig presidential candidate, was a slave owner and a popular figure after the Mexican-American War. Fillmore balanced the ticket as a known, anti-slavery Northerner.

When Taylor became President in 1849, Fillmore was relegated to his nominal constitutional duty as presiding officer of the Senate. President Taylor and Fillmore weren’t close and came from much-different backgrounds.

At the time, Congress was involved in a heated debate about the future of slavery in newly acquired territories and states, and it was Fillmore who presided over the debates in the Senate. President Taylor defied expectations and didn’t endorse the expansion of slavery. Taylor specifically wanted California admitted as a free state.

The efforts of political power broker Henry Clay were thwarted and the Union’s future was uncertain, with secession talk already in the air. Then, President Taylor suddenly died after attending a July 4 event in 1850. The unknown Northerner, Fillmore, became President.

It became clear very quickly that Fillmore believed his constitutional duty was to preserve the union through what became known as the Compromise of 1850. Fillmore worked with a rising Senator, Stephen Douglas, from the rival Democratic Party on a package of laws that admitted California as a free state but granted some important concessions to pro-slavery forces.

Fillmore was conflicted over parts of the Compromise, especially because of his personal experiences. But, as he told Daniel Webster in a letter, he felt it was his constitutional duty to enforce the law.

“God knows I detest slavery, but it is an existing evil, for which we are not responsible, and we must endure it and give it such protection as is guaranteed by the constitution, till we get rid of it without destroying the last hope of free government in the world,” Fillmore said.

The result was that Fillmore had greatly upset members of the Democrats and the Whigs with the Compromise. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act angered Northerners, who saw that President Fillmore would act to compel federal marshals to track down slaves that had escaped to the north.

Fillmore also sent government troops to the South to act against rumors of secession by South Carolina. Pro-slavery forces were also unhappy that slavery had been barred in California.

The Compromise of 1850 also dealt a fatal blow to the Whig Party, which had divided into an anti-slavery northern section and a pro-slavery southern section. At the 1852 Whig convention, Fillmore couldn’t gain support for the presidential nomination he sought at the last moment; General Winfield Scott became a candidate who stood little chance against the Democratic Party.

Fillmore’s last act on the national stage was his nomination as the presidential candidate of the American, or Know Nothing, Party in 1856. The party opposed immigration and Catholics, and Fillmore accepted its nomination without agreeing on its key principles. The remnants of the Whig Party also endorsed Fillmore.

While Fillmore came in third in the 1856 election, he gained 21 percent of the popular vote and 8 electoral votes, which contributed to the defeat of John Fremont, the nominee of the new Republican Party. James Buchanan took the critical election before the 1860s began.

Fillmore made occasional cameo appearances on the national political stage, but he spent the rest of his life as a prominent citizen of Buffalo, where he died in 1874. The New York Times obituary for Fillmore said that “the general policy of his administration was wise and liberal,” but that his enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law was problematic.

“His course in this matter was extremely unpopular with a large portion of the Northern people, and was the occasion of a very general indifference toward him ever after," the newspaper said.