It’s one of the Constitution’s most obscure sections, but for a third time this year President Donald Trump is facing a lawsuit based on the Emoluments Clause.

The clause in Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution says that, “no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or Foreign State.” An emolument is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the returns arising from office or employment usually in the form of compensation or perquisites.”

The clause in Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution says that, “no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or Foreign State.” An emolument is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the returns arising from office or employment usually in the form of compensation or perquisites.”

In January, the watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics (or CREW) sued President Trump in federal court in New York. Then a Washington, D.C. restaurant filed its own lawsuit. And on Monday, officials from the state of Maryland and the District of Columbia lodged their own legal actions against the President.

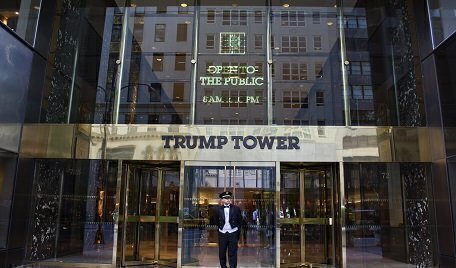

District of Columbia Attorney General Karl Racine and Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh want the Trump Organization to stop receiving payments from foreign government officials who stay at hotels and use other Trump facilities.

Link: Read The Lawsuit

“Fundamental to a President’s fidelity to [faithfully execute his oath of office] is the Constitution’s demand that the President ... disentangle his private finances from those of domestic and foreign powers," the lawsuit reads. "Never before has a President acted with such disregard for this constitutional prescription.” Frosh and Racine, if they succeed in a federal district court in Maryland, also want President Trump’s tax returns presented as evidence.

On Monday, administration spokesman Sean Spicer said the lawsuit was politically motivated. "It's not hard to conclude there are partisan motivations behind today's lawsuit," Spicer said. "The President's interests, as previously discussed, do not violate the Emoluments clause.”

Previously, the Trump Organization said it would donate payments from foreign officials to the Treasury Department, but it is unclear how those payments can be tracked. Last Friday, in a court filing about the CREW lawsuit, Trump’s lawyers made a detailed argument about market-rate payments to Trump business interests as falling outside of the Emoluments clause.

"Neither the text nor the history of the Clauses shows that they were intended to reach benefits arising from a President’s private business pursuits having nothing to do with his office or personal service to a foreign power," said the Justice Department brief.

In recent months, the Emoluments Clause has received more publicity than it has since 2009, when there was a brief public debate about it when President Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Justice Department back in 2009 decided the clause didn’t apply to the Nobel Prize and President Obama since the Nobel Prize committee didn’t represent a King, Prince, or Foreign State, and that two prior Presidents, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, were given the same award while in office.

Constitution Daily’s Supreme Court correspondent, Lyle Denniston, who has covered the Court for 58 years and seen his share of cases, wrote last December about the Emoluments Clause’s rarity as a subject for the courts to consider.

“There is little history surrounding the Clause since it was inserted in the original Constitution in 1787, but what history there is suggests quite strongly that it would mainly be up to Congress to enforce its restriction on foreign largesse for an American president or other federal officials,” Denniston said.

The issue of standing to sue is one important factor, he said. “There is considerable debate about the availability of another potential enforcement mechanism – that is, can any private citizen or private business (say, a competitor) sue? That would have to be tested, to be sure.”

The lawsuit by a state, however, could offer a different challenge. Maryland’s attorney general Frosh is arguing that his state has special standing to sue, based on “Maryland's sovereign interest in enforcing the terms on which it agreed to enter the Union.” Before the federal Constitution was ratified, Maryland’s state constitution had strict clauses barring emoluments. “As a state sovereign, Maryland retains its power to bring suit to enforce those prohibitions today,” Frosh said in his lawsuit.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.