An organization is suing President Donald Trump for conflicts of interest, in what could be the start of an interesting legal debate in court about an obscure constitutional provision.

Creative Commons: Bin im Garten

In recent weeks, the Foreign Emoluments Clause has received more publicity than it has since 2009, when there was a brief public debate about it when President Barack Obama was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

The clause in Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution says that, “no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or Foreign State.” An emolument is defined by Merriam-Webster as “the returns arising from office or employment usually in the form of compensation or perquisites.”

The Justice Department back in 2009 decided the clause didn’t apply to the Nobel Prize and President Obama since the Nobel Prize committee didn’t represent a King, Prince, or Foreign State, and that two prior Presidents, Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, were given the same award while in office.

In 2017, the Foreign Emoluments Clause discussion is different. In recent months, academics have been debating if the clause would apply to Donald Trump’s various domestic and foreign business interests, if he were elected President. Since Trump’s election, the debate has intensified.

On January 11, Trump and his legal adviser, Sheri Dillon, directly addressed the clause and the general topic of conflicts of interest at a press conference. “Just like with conflicts of interests, he wants to do more than what the Constitution requires,” Dillon said. “President-elect Trump has decided and we are announcing today that he is going to voluntarily donate all profits from foreign government payments made to his hotels to the United States Treasury.”

Dillon stressed that acts like foreign officials paying for hotel rooms were voluntary because “paying for a hotel room is not a gift or a present. … It is not an emolument.”

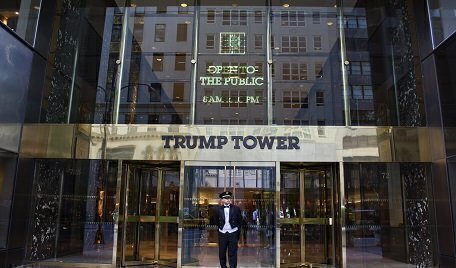

On Monday, the watchdog group Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics (or CREW) sued President Trump in federal court in New York. “The Foreign Emoluments Clause of the Constitution prohibits Trump from receiving anything of value from foreign governments, including foreign government-owned businesses, without the approval of Congress,” the group said in a statement.

In the 37-page complaint, which includes the participation of several law professors, CREW claims it has met the critical question of its standing to sue in federal court because “it has been forced to divert essential and limited resources—including time and money—from other important matters that it ordinarily would have been handling to the Foreign Emoluments Clause issues involving Defendant, which have consumed the attention of the public and the media.”

Constitution Daily’s Supreme Court correspondent, Lyle Denniston, who has covered the Court for 58 years and seen his share of cases, wrote last month about the Foreign Emoluments Clause’s rarity as a subject for the courts to consider.

“There is little history surrounding the Clause since it was inserted in the original Constitution in 1787, but what history there is suggests quite strongly that it would mainly be up to Congress to enforce its restriction on foreign largesse for an American president or other federal officials,” Denniston said.

The issue of standing to sue is one important factor, he said. “There is considerable debate about the availability of another potential enforcement mechanism – that is, can any private citizen or private business (say, a competitor) sue? That would have to be tested, to be sure.”

Another factor is the ability to prove that compensation was paid by a foreign entity with the expectation of receiving a benefit.

“If the payment were for goods or services of a normal kind, and the money was paid at usual market rates, what effect might that have on the business entity’s revenues, its profits, and the ongoing value of the business? Indeed, are profits for a business owned by a President even covered by the Emoluments Clause?” Denniston asked.

Recently, University of Iowa law professor Andy Grewal has raised a related point – that payments to Trump-owned businesses aren’t “office related” unless there is direct payment to him, under a historical definition of the term “emolument.”

“Under the principal definition of emolument, abbreviated here as ‘office-related payments,’ the term refers only to compensation for services performed, whether as an officer, employee, or independent contractor. Under this definition, ordinary business transactions between foreign governments and the Trump Organization do not violate the Foreign Emoluments Clause. Only transactions conducted at other than arm’s length, or transactions involving the provision of services by the President personally, establish potential violations,” Grewal argues.

In its complaint, CREW says that “the theory of the Foreign Emoluments Clause—grounded in English history and the Framers’ experience—is that a federal officeholder who receives something of value from a foreign power can be imperceptibly induced to compromise what the Constitution insists be his or her exclusive loyalty: the best interest of the United States of America. … the Framers concluded that the proper solution was to write a strict rule into the Constitution itself, thereby ensuring that shifting political imperatives and incentives never undo this vital safeguard of freedom.”

For now, the issue rests with the United States District Court For The Southern District Of New York. CREW has indicated it will seek separate actions in related cases.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.