Note: Landmark Cases, a C-SPAN series on historic Supreme Court decisions—produced in cooperation with the National Constitution Center—continues on Monday, Oct. 26th at 9pm ET. This week’s show features Lochner v. New York.

In one of the most widely condemned cases in U.S. history, the Supreme Court determined that the right to freely contract is a fundamental right under the 14th Amendment.

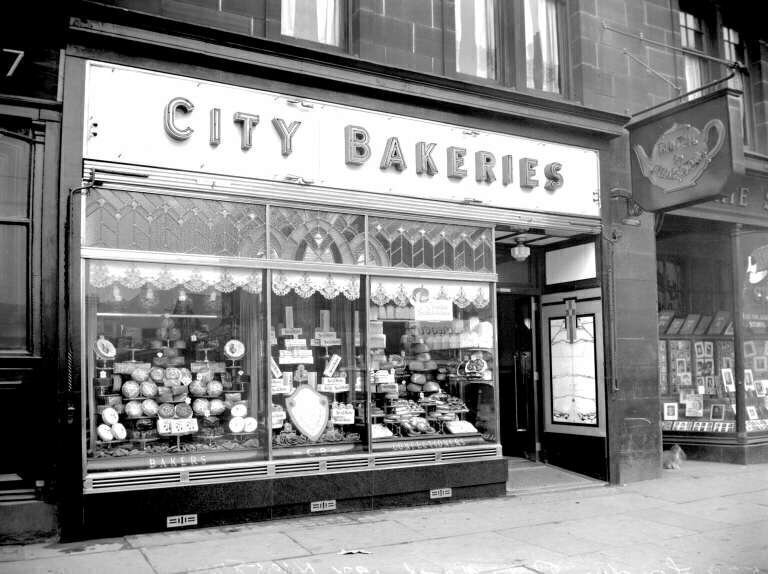

The story of the Court’s 1905 opinion in Lochner v. New York begins in 1895, when New York State passed the Bakeshop Act, one of the state’s earliest labor laws, in an effort to regulate sanitary and working conditions in New York bakeries. A section of the act stated that “no employee shall be required or permitted to work in a biscuit, bread, or cake bakery or confectionary establishment more than sixty hours in any one week, or more than ten hours in any one day.”

At the time, Joseph Lochner was a Bavarian immigrant who owned Lochner’s Home Bakery in Utica. In 1899, Lochner was charged with violating the Bakeshop Act, as he had allowed an employee to work for more than sixty hours in one week. For this, Lochner was fined the requisite $25. Two years later, in 1901, Lochner was charged and convicted for a second offense of the Bakeshop Act’s 60-hour provision, this time paying a $50 fine.

Lochner decided to appeal the Oneida County Court’s fine. His lawyer, William Mackie, argued that the regulations interfered with the right to earn a living. The Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court disagreed, and by a 3-2 vote, upheld Lochner’s conviction. Lochner and Mackie then brought their appeal to the New York Court of Appeals, but they lost in a 4-3 decision.

Upon his appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, Lochner changed attorneys. Henry Weismann, his new lawyer, was not the most likely candidate to argue the case. Prior to becoming an attorney, Weismann had been an instrumental part of passing the Bakeshop Act—he had been a lobbyist for the Journeyman Bakers Union, and was the editor of the The Baker’s Journal, the union’s newsletter. He led the successful fight for the 60-hour work week.

However, in 1897, Weismann left the union. He soon opened a bakery of his own while he was studying to become a lawyer. His experience as a bakery owner changed his view of the Bakeshop Act, and, as he wrote, he experienced “an intellectual revolution, saw where the law which I had succeeded in having passed was unjust to the employers.”

With his newfound convictions, Weismann argued on behalf of Lochner that the Bakeshop Act violated the Constitution’s protection of the “liberty of contract,” or an employer’s right to make a contract with his employee free from governmental interference. Weismann’s brief argued that it was wrong that “the treasured freedom of the individual … should be swept away under the guise of the police power of the State,” and that the law was a violation of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause.

The Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, agreed. In an opinion written by Justice Rufus Peckham, the Court held that the offending section of the Bakeshop Act was unconstitutional, as it did not constitute a legitimate exercise of state police powers. The Court declared that the law was an interference with the right of contract between employers and employees, and that “the general right to make a contract in relation to his business is part of the liberty of the individual protected by the Fourteenth Amendment of the Federal Constitution.” Therefore, the Court concluded, the right to contract one’s labor was a “liberty of the individual” protected by the Constitution.

In making their decision, the Court acknowledged that the states may legitimately regulate certain types of labor contracts through their police powers, but only in specific circumstances. The baking industry—unlike the mining industry, for example—was not one of those circumstances, as it was not an “unhealthy” trade. The Court said that, in order to approve of a state’s use of its police powers to regulate contracts, the question was whether the legislation was:

a fair, reasonable and appropriate exercise of the police power of the State, or is it an unreasonable, unnecessary and arbitrary interference with the right of the individual to his personal liberty or to enter into those contracts in relation to labor which may seem to him appropriate or necessary for the support of himself and his family?

Therefore, because the Court found that the baking industry was no more or less healthful than other common professions, and that the law was not related to the health of the employees, it was an invalid exercise of the state’s police powers.

The legacy of Lochner v. New York immediately took shape. Over the next 30 years, during what is now commonly referred to as the “Lochner era,” the Court struck down laws regulating labor conditions under Lochner’s conception of the 14th Amendment.

But in 1937, the Court changed course and began to allow some government regulation of the labor market, as was the case in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (although that ruling did not explicitly overturn Lochner). Today, as was stated in the 1955 case of Williamson v. Lee Optical of Oklahoma, “[t]he day is gone when this Court uses the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to strike down state laws, regulatory of business and industrial conditions, because they may be unwise, improvident, or out of harmony with a particular school of thought.”

While Lochner may now be viewed in a negative light, it did leave a significant legacy that impacts the court to this day. Lochner, though not the first case to do so, found that the due process rights of the 14th Amendment were not just “procedural,” but were also “substantive.” While “procedural” due process rights limit the means by which the state may deprive a person of their life, liberty, or property, “substantive” due process rights limit the types of activities and rights that the government may regulate by deeming them to be fundamental.

This line of thinking, which led the Court to protect the right to contract, also led to the protection of rights that many Americans hold dear today, including the right to privacy.

Joshua Waimberg is a legal fellow at the National Constitution Center.