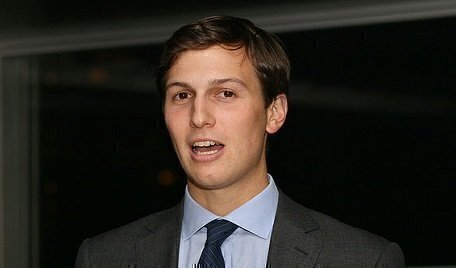

Several news sources reported on Monday that President-elect Donald Trump will name his son-in-law, Jared Kushner, as a senior White House advisor on Wednesday. The move could test an anti-nepotism law on the books since 1967.

The appointment had been expected since last weekend, when Kushner’s attorney issued a statement about a potential conflict if Kushner were to be named to an official executive branch position."Mr. Kushner is committed to complying with federal ethics laws and we have been consulting with the Office of Government Ethics regarding the steps he would take," said Jamie Gorelick, a partner at the law firm of WilmerHale,

"Mr. Kushner is committed to complying with federal ethics laws and we have been consulting with the Office of Government Ethics regarding the steps he would take," said Jamie Gorelick, a partner at the law firm of WilmerHale, in a statement. "Although plans are not finalized, Mr. Kushner would resign from his position at Kushner Companies and divest substantial assets in accordance with federal guidelines."

Axios’ Mike Allen was the first to report Kushner’s appointment and Allen said that Kushner is seeking job applicants for his staff. It’s unknown if Kushner would receive compensation from his White House position, which Trump plans to discuss at a Wednesday press conference.

One potential conflict is related to a 1967 statute called the Federal Anti-Nepotism Statute. The law, known as Section 3110, was passed as part of a Postal Service reform law, and it states that an executive agency official can’t appoint relatives, including sons, daughters and sons-in law, to “a civilian position in the agency in which he is serving or over which he exercises jurisdiction or control.”

There has been considerable debate about Kushner, or another Trump family member, serving in an official White House role and how that relates to the statute.

A similar controversy also took place in the 1990s when President Bill Clinton asked Hillary Clinton to lead a health-care task force that held closed-door meetings. In a 1993 lawsuit, a federal judge ruled that some of the Clinton task-force meetings needed to be held in public, but he also rejected the argument that the First Lady was a “government employee.”

In the years after that, several academics have argued that the Federal Anti-Nepotism Statute doesn’t really apply to the President, since the President has powers directly vested by the Constitution’s Appointments Clause. Article II, Section 2, provides that some officials need to be approved by the Senate, while other “inferior” officers may be appointed directly by the President.

In 2012, Gerard Magliocca from the Indiana University School of Law argued that Section 3110 clearly didn’t apply to the President. “First, as far as I can tell, this is the only statutory limit on the President’s authority to choose his political appointees. Separation-of-powers would suggest that Congress cannot intrude so bluntly into his discretion to choose close advisors,” Magliocca wrote on the blog Concurring Opinions.

Another argument is that the White House itself is not an agency of the Executive Branch, and that the Anti-Nepotism Statute doesn’t apply in this case. And there is some debate about the applicability of the law to Kushner if he doesn’t receive financial compensation.

A federal court appeal related to the Clinton case included language that discussed the White House as a government agency. “Although section 3110(a)(1)(A) defines agency as ‘an executive agency,’ we doubt that Congress intended to include the White House or the Executive Office of the President,” said Judge Laurence Silberman. “The anti-nepotism statute, moreover, may well bar appointment only to paid positions in government,” he added. However, there is disagreement about the nature of that language in that opinion, and if it was part of the controlling opinion.

Law professor Steve Vladeck from the University of Texas told CNN in November that while the statute could be challenged, the risk is that a court could rule that any action taken by the relative in an official role could be questioned.

"While it's true that the penalty for violation of the statute is just to withhold salary or other financial remuneration from the wrongfully appointed employee, there's also the possibility that any action taken by such a wrongfully appointed employee could be subject to legal challenge and potentially even be voidable," Vladeck said.

Two recent White House ethics counsels, Richard Painter and Norman Eisen, also believe an appointment such as Kushner’s would violate the Anti-Nepotism Statute.

Before 1967, there was a rather long history of presidential relatives serving in appointed and unofficial government positions. The most famous example was President John F. Kennedy’s nomination of his brother, Robert, to become Attorney General. Robert Kennedy was confirmed in a voice vote by the Senate in 1961 and he served until September 1964.

Other Presidents retained relatives at the White House in various roles, including James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, John Tyler, James Buchanan, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt and Dwight Eisenhower. Kennedy also appointed his brother-in-law, Sargent Shriver, as the first head of the Peace Corps.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.