The Supreme Court agreed on Friday to decide, on a speeded-up schedule, a dispute over the Trump Administration’s decision to add to the 2020 census a question about the citizenship of everyone in America. The ruling that emerges, however, will not be directly on the legality of asking that question but could have a bearing on that controversy.

The specific issue that is now before the Justices, in the appeal by the Administration, is whether state and local governments that are challenging the addition of that question may require Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross to testify, under oath, about why he pressed for that. Ross’ department includes the Census Bureau, so he is the key official in deciding how to conduct the once-a-decade census.

The specific issue that is now before the Justices, in the appeal by the Administration, is whether state and local governments that are challenging the addition of that question may require Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross to testify, under oath, about why he pressed for that. Ross’ department includes the Census Bureau, so he is the key official in deciding how to conduct the once-a-decade census.

A secondary issue is what kind of evidence a federal trial judge may consider when deciding whether asking the question is illegal or unconstitutional. The judge this week just concluded a trial on the overall dispute over asking that question, but has not yet ruled and has not yet even decided what evidence he will take into account.

One of the claims of those challenging the question’s addition is that Ross decided to do so because of a bias against non-citizens living in the U.S., based on ethnic or racial identity, in violation of the Constitution. The other claim is that Ross acted in an arbitrary manner, in violation of federal law.

The Justices put the Administration’s appeal on an expedited basis, with all written legal briefs due by February 4 and with a hearing set for February 19. A final decision in the case at an early point is needed, government lawyers argued, to allow the Census Bureau to make its final plans for taking the census in 2020.

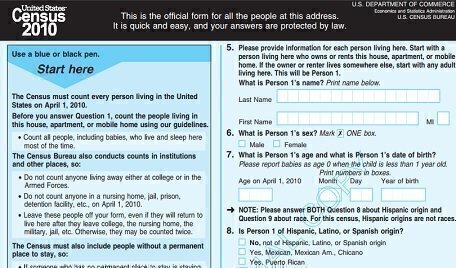

The Constitution requires that everyone living in the country must be counted in the census, whether or not they are citizens and whether or not they are living in the country illegally as undocumented immigrants.

The final count that results is a vital number because it determines the population that is used to divide up the seats in the U.S. House of Representatives, in state legislatures and some local governing bodies. The state totals also are a key to where billions of dollars in federal spending are made.

The state and local governments contesting the use of the citizenship question have argued – with support from some of the Census Bureau’s own experts – that the presence of this inquiry on the census questionnaire will result in serious under-counting of the immigrant population, legal or illegal, because households where immigrants are living will not want to risk disclosure that could lead to deportation. An undercount will seriously skew the resulting distribution of population, the challengers argue.

Commerce Secretary Ross has testified before Congress that he decided to ask the citizenship question at the request of the Justice Department, on the premise that the results are needed by that Department in enforcing the federal Voting Rights Act. But the challengers have produced evidence that Ross, at the instigation of the White House, actually pressed the Justice Department to ask the question as a way to diminish the count of immigrants.

The trial judge in New York City, U.S. District Judge Jesse M. Furman ruled that Ross had acted in “bad faith” in giving his official reasons for adding the citizenship query, and the judge then ordered Ross to submit to four hours of questioning, under oath, about his actions.

The Supreme Court last month temporarily blocked the questioning of Ross, but allowed the trial before Judge Furman to go ahead and allowed the challengers to question under oath other government officials, including a Justice Department official. The official from Justice said when questioned that the Department actually did not need the data that the citizenship question would produce for any enforcement of the voting rights law.

As the case now will unfold before the Supreme Court, the Justices will be deciding these specific issues:

First, does Commerce Secretary Ross have to submit to questioning under oath, or does Judge Furman have to accept Ross’s own statements about why he acted to add the question? Second, what is the legal standard for deciding when a high government official may be required to give testimony under oath about the reasons for taking official action? Third, must Judge Furman, in deciding the ultimate question of the legality or constitutionality of the citizenship question, have to base that ruling solely on the documents that the Commerce Department produced about its process for developing that option, or may the judge also take into account what government officials said when questioned about Ross’s actions?

The judge has said that, as he approaches a decision on the validity of asking the citizenship question, he would proceed on two levels: first, making a decision based on the Commerce documents alone, and, second, on the results of the questioning of officials. If it turns out that the Supreme Court were to rule against the use of that second level of evidence, the judge would ignore it in his decision.

In urging the Justices not to hear the case, the state and local governments challenging Ross’s decision argued that the case involves only the routine mode of judicial review of government action, and does not even reach the ultimate question of whether it would be illegal or unconstitutional to include the question on census forms.

Judge Furman finished hearing witnesses and taking evidence this week, and presumably was ready to begin making his decision. It is unclear whether he will have to halt that process to await the outcome of the Supreme Court’s review. But, as of now, there does not appear to be any order from the Supreme Court that would require him to stand aside to await the Justices’ decision.