Convinced that it must act quickly to settle the issue, the Supreme Court agreed on Friday to decide the legality of adding a question about citizenship to the 2020 census.

The Court, opting to bypass the normal route of the case through a federal appeals court, will hold a hearing on the case in the current term’s final week of scheduled argument sessions in April.

The Court, opting to bypass the normal route of the case through a federal appeals court, will hold a hearing on the case in the current term’s final week of scheduled argument sessions in April.

The outcome of the dispute will have a direct impact on how many seats some larger states will have in the U.S. House of Representatives, how election districts are shaped at every level of government over the next ten years, and how some $700 billion in federal money is distributed.

A federal judge ruled in January that it would violate several federal laws to add a citizenship question to the census questionnaire that will go to every household next year. Although the case does not directly involve a constitutional dispute, it has implications for the requirement in the Constitution that everyone living in America – citizen or not, in the country legally or not – must be counted.

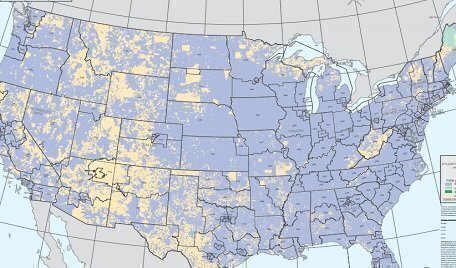

Opponents of the Trump Administration plan to add the citizenship question contend that it will make the final census count wrong, because the question will discourage responses to the questionnaire by households where non-citizens and undocumented immigrants are living. Those households, the challengers argue, may simply refuse to fill out the document for fear that it may expose some of those individuals to the risk of deportation.

The Administration’s main argument is that inclusion of the question on the census form is the best way to gather specific data for use by the Justice Department as it handles cases on voting rights cases that depend upon population data.

The Justice Department at one point did support that claim, but backed off of it later. Despite that shift in stance, the Administration has argued in its Supreme Court filings that Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross – who supervises the census – genuinely believed that the information was necessary for voting rights cases, and his belief should be sufficient.

When the case went to trial in a federal court in New York City, there was evidence that White House officials had urged Secretary Ross to include the citizenship inquiry. That led the challengers to contend that Ross acted out of a purpose to discriminate against Hispanics as a result of ethnic bias. That was a constitutional claim, but it was rejected by the trial judge who ruled against inclusion of the citizenship question, and that claim apparently does not remain at issue before the Supreme Court.

In appealing the case to the Supreme Court, the Administration raised two legal issues. The Justices’ order granting review said nothing about what was being accepted, so presumably it plans to answer both.

The first, and clearly most important issue, was whether the Commerce Secretary acted illegally in deciding to ask every household in America about the citizenship of every occupant. (The census formerly included such a question, but that was last done in the 1950 census – almost three-quarters of a century ago.

The second issue is a technical one about the power of federal trial judges to decide a case challenging a government action based only on the evidence that the government agency supplied to justify its action, or if it may demand further data or information to test the real reasons or motives officials may have had for their decision.

The challengers wanted to question Commerce Secretary Ross, in person and under oath, to test whether he was actually motivated by ethnic bias in posing the citizenship question. In an earlier order by the Supreme Court while the case was still going through the trial court, the Justices barred that plan without saying whether it was proper. That issue is no longer in the case, because the trial is over and the challengers have dropped the idea.

While that second question is significantly less important than the first, an answer to it by the Justices may have an important influence on how much high government officials could be insulated from being directly questioned about their actions when those actions are targeted in a lawsuit, especially in a case where there is a claim of unconstitutional discrimination.

The Court’s order granting review did not specify a date in April when the case would be argued, other than to say it would come during the week of April 22. The Court already has filled all of the morning slots for hearings in that week of the April sitting, but it could add an afternoon session or add another day. The Court silently turned aside the suggestion that it might want to schedule a special sitting in May, just for the census case.

Everyone involved in the case as it developed in the Supreme Court had agreed that, if the Justices were going to decide the dispute, it should do so on an expedited basis, without waiting for review first by a federal appeals court, because the Census Bureau has said it needs to finalize the content of the census questionnaire by the end of June.

That questionnaire goes to every household, and the occupants have a legal obligation to fill it out. However, a key issue in the case is what impact on the voluntary response rate can be expected from inclusion of a question that may be unsettling to some households or individuals.

The Trump Administration insists that, since there is a legal duty to fill out the questionnaire, any problem of an under-count is not the fault of the questions asked but of the individual who fails to respond.

The census, taken every ten years, is one of the oldest acts of the American government. The very first census was taken in 1790, one year after the new government established by the Constitution had actually begun operating. Of course, the method of taking the census has grown much more sophisticated in modern times.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.