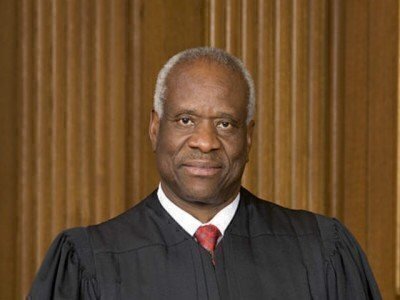

In nearly 28 years on the Supreme Court, Justice Clarence Thomas has been its most unwavering “originalist.” That means that he reads the Constitution as meaning today what he believes those who wrote it meant back then, no matter how conditions may have changed in America in the meantime.

That perception has made him the most willing Justice on the modern Court to cast aside precedents, however long they have remained on the books, as unfaithful to what he describes as the original constitutional meaning.

That perception has made him the most willing Justice on the modern Court to cast aside precedents, however long they have remained on the books, as unfaithful to what he describes as the original constitutional meaning.

It thus was no surprise when on Tuesday he singled out another precedent as a potential for overruling. This time, though, it was one of the sturdiest shields protecting freedom of expression in America: the Court’s 55-year-old decision in New York Times v. Sullivan.

That 1964 decision, an interpretation of the Free Press and Free Speech Clauses of the First Amendment, spelled out a constitutional formula that has made it all but impossible for public officials to win lawsuits claiming that their reputations were defamed (or libeled) by the press or other public communicators. In decisions three years and then ten years after that, the Court extended the limits on libel lawsuits to those filed by public figures, such as celebrities – major or minor.

In 1991, the 200th anniversary year of the First Amendment (and the other nine parts of the Bill of Rights), longtime Supreme Court journalist Anthony Lewis of The New York Times wrote a celebratory book about the Sullivan decision. It took its title, “Make No Law,” from the First Amendment itself.

Here is Lewis’s judgment about the decision’s historical significance: “Without New York Times v. Sulllivan, it is questionable whether the press could have done as much as it has to penetrate the power and secrecy of modern government, or to confront the public with the realities of policy issues.”

On Tuesday, Justice Thomas – in an opinion not joined by any of his colleagues – denounced that ruling and the Court’s later rulings that expanded its protection as “policy-driven decisions masquerading as constitutional law.”

He did not call explicitly for it to be overturned right away, but his ultimate desire for it to be discarded was unmistakable in the history lesson he told in the 14 pages of his opinion. Perhaps it was only a coincidence, but Thomas chose to take his stand in a case in which neither side had even discussed the Sullivan decision and a case that was itself extremely high in profile, thus drawing more attention to it.

It was the first “me-too” case to reach the Court – that is, a dispute growing out of the recent social and political movement of women who were victims of sexual assault to go public with their accusations against high-profile men. It involved claims that the accused man had retaliated by attempting to ruin the woman’s reputation, leading her to file a libel lawsuit – a lawsuit that ultimately failed the test that originated in the Sullivan decision.

The lower court decision appeared to be based on the finding that, if a person with some public celebrity of their own, inserts herself into the public controversy stirred up by the “me-too” movement, that is enough to limit her lawsuit by the Sullivan formula as it was extended to public figures in 1967 and 1974.

Enhancing the case’s visibility was the fact that it involved an accusation of rape against one of America’s best-known entertainment figures – actor, comedian and TV personality Bill Cosby – who has been convicted and imprisoned for one of more than two dozen incidents of claimed sexual assault.

And it involves a former actress and nightclub showgirl, Kathrine Mae McKee, part of whose public reputation was her long-time romantic relationship with Hollywood entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. She sued Cosby for libel after one of his associates allegedly published a letter that she said defamed her.

And, coincidentally, the failure of McKee to get her case before the Supreme Court could have implications for a defamation lawsuit now working its way through state court in New York against President Trump by a former contestant on his TV show “The Apprentice,” Summer Zervos. She claims that Trump’s denial of her claim of unwanted groping harmed her reputation.

Justice Thomas mentioned none of these enhancements of the case in urging the Court to find an appropriate case, sometime in the future, to reconsider the Sullivan decision and the later precedents that enlarged the First Amendment umbrella first spelled out in 1964.

Before that ruling, the Court had never confronted the question of how the First Amendment might limit the scope of the law of defamation. Up to that point, defamation law was merely a matter of state law. Justice Thomas, in one of his points Tuesday, argued that state governments could be trusted to enforce their libel laws in ways that would be sensitive to First Amendment values while protecting reputations of those who have some public prominence.

The basic formula laid down by the Court in 1964 is that a public official (and, in later decisions, other public figures) cannot win their claims of libel or defamation unless they prove that what was said about them was not only false but also was published or uttered while knowing it was false or without caring whether or not it was false.

Justice Thomas quoted the late Justice Byron R. White, a critic of that formula, as having said that it was an “almost impossible standard” to be met by public figures who sue for libel.

The separate Thomas opinion was not a dissent from the Court’s order refusing to hear the McKee appeal. He said he agreed with his colleagues that her case was only a dispute about the facts of her particular case, although her lawyers had attempted to frame the question they wanted the Court to answer as a plea for clarification of who qualifies as a public figure under the prior precedents.

It would have taken the votes of four Justices to grant review of that case, and that will be the minimum requirement if another case comes along that four Justices think would pose a solid test of the continuing effect of the Sullivan line of decisions.

It could be that some of the Court’s other conservative Justices might join Thomas in voting to hear some future appeal. It is perhaps doubtful that he could attract one of his conservative colleagues, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. In an appearance at a law school function earlier this month, the Chief Justice remarked: “I’m probably the most aggressive defender of the First Amendment on the Court now.”

Even without a new appeal to test how the current Justices feel about the 1964 precedent and its sequels, Justice Thomas’s views could begin to have an impact. It may encourage further debate in the legal academy about the future of New York Times v. Sullivan. And it could lead lawyers who practice in the field of libel to start looking for new cases that could become tests of whether Thomas has any allies in questioning that precedent.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.