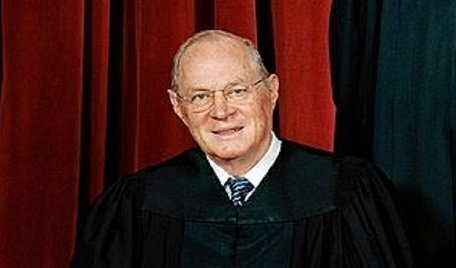

Lyle Denniston looks at a case about environmental rights filed by teenagers that could lead to one of Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s last significant acts on the Court before his retirement next week.

Just days before retiring, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy is facing a question that has been quite familiar in his 30-year career on the Supreme Court: Is it time to recognize a new and fundamental constitutional right? That is the ultimate issue as he ponders an Oregon case that is all about America’s environmental future.

Just days before retiring, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy is facing a question that has been quite familiar in his 30-year career on the Supreme Court: Is it time to recognize a new and fundamental constitutional right? That is the ultimate issue as he ponders an Oregon case that is all about America’s environmental future.

The Trump Administration has taken to Justice Kennedy its attempt to shut down a lawsuit in which U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken of Eugene, Ore., established a novel constitutional guarantee: “a right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life.” She drew strong inspiration for that decision from Kennedy’s opinion three years ago recognizing for the first time a right to same-sex marriage.

During his years on the Court, Kennedy gained a reputation for interpreting the Constitution’s broadly worded guarantees to include new rights or to significantly safeguard existing rights: for gays and lesbians, for women seeking abortions, for minority youths seeking college entry, for teenagers who commit crimes, as examples.

The Justice embraced an expanding perception of the Constitution’s promise of “liberty,” arguing that what it protected changed and grew over time. In fact, Judge Aiken in her opinion in the Oregon case quoted this guidance from Kennedy’s same-sex marriage ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges: “The identification and protection of fundamental rights is an enduring part of the judicial duty to interpret the Constitution. … History and tradition guide and discipline this inquiry but do not set its outer boundaries.”

Aiken noted that Kennedy also had written in that decision that the Constitution allows future generations to protect “the right of all persons to enjoy liberty as we learn its meaning.”

The Trump Administration has been trying – as the Obama Administration before it did – to end the case in Judge Aiken’s trial court. President Trump’s lawyers have mounted a multi-pronged challenge to nearly every facet of that case – whether the judge has any authority to decide it, whether she has any power to order government officials to give testimony, whether the challengers have any rights to demand legal materials from the government, and whether the judge’s plan to begin a five-week trial on October 29 should be blocked.

This case, the Trump legal team told Kennedy, “is an attempt to redirect environmental and energy policies through the courts rather than through the political process, by asserting a new and unsupported fundamental right to certain climate conditions.” This, the filing contended, would upset the division of government power specified in the Constitution itself.

The Oregon case is one of several filed in recent years by teenagers, seeking to hold the government responsible for harms to the environment that will make the planet uninhabitable for them as they grow up. Their objective is to get a court order that would force the government to come up with a nationwide plan to reduce “greenhouse gas” emissions from carbon dioxide, produced by burning coal and oil, to meet special goals.

The Supreme Court refused to hear one of those lawsuits in December 2014, but the legal advocacy groups pursuing the claims have continued energetically to test their theory in court. The case before Judge Aiken, filed by 21 teenagers and a group named Earth Guardians, will reach its third anniversary in August. Besides the teenagers who joined in the lawsuit, the challengers also include a legal guardian representing children who will be born in the future.

The Trump Administration took its plea to Justice Kennedy after the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit refused to intervene and declined to rule on the government request to dismiss the case without any further pre-trial legal maneuvering.

Kennedy handles emergency pleas from the geographic area of the Ninth Circuit, which includes Oregon. Although Kennedy has scheduled his retirement to become effective a week from Tuesday, he continues to have the full power of a Justice to act on a plea like the government’s. He can resolve it alone or share it with his eight colleagues – the more common practice these days. (If Kennedy has not done his part by July 31, the dispute will simply be passed to another Justice. A replacement for Kennedy is not likely to be approved by the Senate until this fall, at the earliest.)

At this point, the Trump Administration’s opening plea to the Justice was to put all of the proceedings before Judge Aiken on hold until after she rules on two government motions to end the case. (The judge held a hearing on those motions last Wednesday and has promised “a formal written opinion,” without saying when that would be released.)

In both of its filings with Kennedy, the Administration has also made the quite unusual suggestion that the Court treat those filings as a request for full review leading to a decision to stop the case entirely. Its second filing came on Friday in a letter to alert the Justice to the Ninth Circuit Court’s latest ruling refusing to interrupt Judge Aiken’s proceedings.

It would take the votes of four Justices to grant full review, and five to decide the case if that review is granted.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011 and has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com.