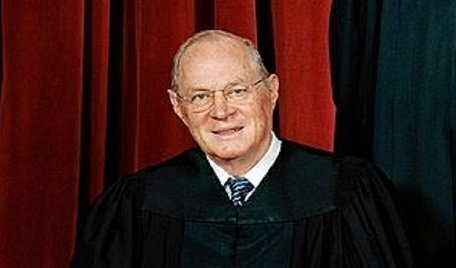

Over the years, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy has become the Supreme Court’s most energetic defender of gay rights, one of its true devotees to free speech, and a sympathetic defender of religious believers. Now, a lengthy hearing before the Justices on Tuesday showed, he has to find a way to reconcile all three.

After 88 minutes of hearing, in the high-profile civil rights case of Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, it seemed that he is likely to hold the deciding vote on a deeply fractured outcome. And, if that happens, he could well assign the case to himself to write the final decision. It won’t be easy, he himself demonstrated.

After 88 minutes of hearing, in the high-profile civil rights case of Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission, it seemed that he is likely to hold the deciding vote on a deeply fractured outcome. And, if that happens, he could well assign the case to himself to write the final decision. It won’t be easy, he himself demonstrated.

The case, on the facts, is about a Lakewood, Colo., retail bakery operator, Jack Phillips, who has refused to create a special cake for a gay couple’s wedding reception, because his religious beliefs are opposed to such marriages and he believes his custom cakes convey a message of approval to a wedding ritual. He has been ordered by state agencies to end that practice, finding it to be a form of illegal discrimination based on sexual orientation; state public accommodations law includes protection in such situations.

The case, on the law, is one of the most important legal sequels to the Supreme Court’s 2015 decision creating a constitutional right for same-sex marriage, and is a very important follow-up to its 2014 decision that a religiously devout business owner does not have to obey a federal law mandating access to birth-control methods for the company’s female workers.

When decided, it may well set a major precedent on when religious objections to such marriages can justify a business refusal to sell goods or services to such couples. Does a right to marry carry full protection for the customs and opportunities associated with marriage? If a baker can refuse equal service, what other business may do so? More generally, when must anti-discrimination law yield to private religious beliefs?

From Tuesday’s argument, it was easy to conclude why Justice Kennedy may hold the “swing vote.” Here’s why:

Among the Court’s more liberal members, Justice Sonia Sotomayor suggested that cakes were for eating not for expressing messages, Justices Elena Kagan and Ruth Bader Ginsburg wondered skeptically why bakers’ creations were more expressive than, say, hair stylists’ or tailors’, and Justice Stephen G. Breyer worried that, if the Court did not draw clear lines, anti-discrimination laws of all kinds would be seriously threatened. (Recall, too, that those four had dissented when the Court protected religious business owners from complying with a birth-control mandate.)

Probably safe, then, to count those four as likely to cast votes for the Colorado civil rights law and its enforcement against Masterpiece Bakeshop.

Might Kennedy add his vote to that bloc? He might: he expressed worry that a ruling in favor of the baker would lead bakers across the country to boycott same-sex marriages, and so those couples would be almost everywhere denied access to a commercial product – a wedding cake. In other words, he appeared to be concerned that a ruling against the Colorado law would be taken as a wider invitation to discriminate against gays. He talked sympathetically of the feelings of ostracism of gay people.

Among the Court’s more conservative members, their reactions were somewhat more opaque than were those of Justices on the other side of the ideological divide. Howevcr, Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., was quite aggressive in questioning lawyers for the state civil rights commission and for the gay couple involved in the case, and he several times implied that he was concerned about a precedent putting religious believers in jeopardy in commercial context, and he suggested that he detected hostility in the work of the Colorado agency. The newest Justice, Neil M. Gorsuch, made clear he, like Alito, was concerned about a slippery slope for business people with strong religious values. Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., dwelled on a hypothetical about how to protect a Christian legal service firm from having to take on gay rights causes. Justice Clarence Thomas, as usual, said nothing, but his strong sentiments in favor of religious freedom are well known. He, along with the Chief Justice and Alito, were in the majority in the birth-control mandate ruling. (Kennedy, too, was in that majority, but with separate views of his own.)

Probably reasonably safe, then, to count the four conservatives as sufficiently sympathetic to Jack Phillips’ plight that they could comfortably vote to protect him and similar devout merchants.

Kennedy, as it turned out in the latter half of Tuesday’s hearing, might very well join the conservative bloc. He was deeply troubled, he made quite clear, about what he detected as anti-religious comments made by one member of the Colorado agency. And he suggested that tolerance and accommodation were strong community values, leading him to wonder if gay couples turned away by one bakery might simply seek out another for their cakes.

The nine Justices have several months of hard deliberations ahead of them before settling on a decision in this case. But Kennedy might well be able, in the end, to lead a majority in a very narrow decision against the Colorado commission, but not necessarily in favor of Jack Phillips and other religiously-oriented businesses. He could craft a ruling, for example, that would return the case to state courts in Colorado, to examine whether the civil rights commission’s record was flawed in cases involving enforcement against religious persons or entities.

If, however, the large issues have to be decided in order to resolve the Masterpiece Cakeshop case, Kennedy – or another author of a majority opinion – will have to decide what commercial activity is a form of expressive speech, and – if it is a form of speech — just when it can be curbed when it works against a protected category of people. The flood of hypothetical questions put forth on Tuesday will surely complicate the search for such a principle, and especially one that actually would be workable.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011 and has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com.