Editor's note: This blog post from our friends at the African American Museum in Philadelphia first ran on June 18, 2011. We changed some of the dates to make the museum's anniversary current with this week.

This weekend, the African American Museum in Philadelphia will celebrate its 39th anniversary. This is an important milestone for our institution, but the dates on which we commemorate– June 18th and 19th – have a poignant meaning that reaches back to much further than our own founding.

It was on these days in 1865 that the Union Army brought news of emancipation to African Americans in one of the farthest corners of the Confederate States, Galveston, Texas, effectively marking the death-knell of slavery in the United States.

Many of us were taught in school that the American Civil War was fought solely to end slavery in the United States. In truth, while this may have been the case for some sympathetic whites in the North, and was certainly the case for many African Americans, enslaved and free, who foresaw the implications of this conflict on their status within the nation, it wasn’t until the middle years of the war that ending slavery took on any real sense of urgency for the federal government and its troops.

In September 1862, watching his Union Army suffer heavy casualties in conflict, unsure of the outcome of the war, and coming to understand that the South was greatly benefiting from its enslaved labor force, Lincoln penned a warning to the rebel states: Lay down your arms by January 1, 1863, or federal forces will emancipate your slaves.

Enslaved Africans and African Americans had long been agents of their own freedom. Some were able to purchase their freedom and that of their families. Others simply stole away, using the complex network of the Underground Railroad to reach safety, or, during the Civil War, traveled to Union camps where they sought both shelter and ways to aid the Union cause. Others were lucky enough to be manumitted, through state actions or directly by the individuals who claimed ownership of them.

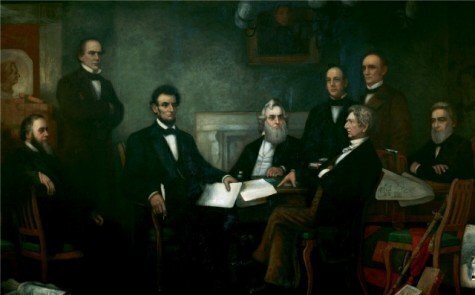

But prior to the ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865 – which banned slavery and involuntary servitude except as punishment for a crime – there was no greater enforceable demand for freedom than that given by the president when he followed through on his threat by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

But prior to the ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1865 – which banned slavery and involuntary servitude except as punishment for a crime – there was no greater enforceable demand for freedom than that given by the president when he followed through on his threat by issuing the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

The proclamation did not free all enslaved people. Rather, it freed slaves in only those areas of the country that Lincoln identified as being in rebellion. The status of those enslaved in slave-owning Union states - Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, Missouri - remained unchanged. Still, as Union troops pushed south and west, enforcing Lincoln’s edict as they traveled, they further weakened the institution of slavery in every corner of the country.

It took over two years for the news of emancipation to officially reach Galveston, Texas. When it arrived on June 19th, it was a time of celebration for the African Americans who had longed for this day to arrive, and who remembered those who had not lived to see it come. While there would be a world of change awaiting them, this day - remembered each year as Juneteenth - was and continues to be a day for celebrating the end of slavery, the beginning of a new chance at life, and the remembrance of all those who made it happen.