In a ruling almost certain to be swiftly challenged in the Supreme Court, a federal trial judge in New York City on Tuesday barred the Trump Administration from asking everyone during the 2020 census about their citizenship.

The ruling, if it withstands an appeal, would be crucial to states that have large populations of non-citizens and Hispanics. Those are the groups that the judge found would likely be under-counted if citizenship were made a question on the census form that goes to every American household.

The ruling, if it withstands an appeal, would be crucial to states that have large populations of non-citizens and Hispanics. Those are the groups that the judge found would likely be under-counted if citizenship were made a question on the census form that goes to every American household.

U.S. District Judge Jesse M. Furman ruled that Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross, who is the overseer of the Census Bureau, and his aides had engaged in “egregious” violations of federal law in deciding to add the citizenship inquiry. The judge turned aside a separate constitutional challenge, finding that those opposed to the citizenship question had not offered enough evidence to support the claim that racial bias was the real reason for Ross's action.

The Supreme Court is already scheduled to hold a hearing on this dispute on February 19, but that is currently scheduled to be on an issue that may now have disappeared because of the way Judge Furman went about deciding the citizenship issue. Thus, the Administration is likely to urge the Supreme Court to convert its review to the specific question of its authority to question the nation’s people about citizenship.

The issue now before the Justices is whether it was illegal for those challenging Ross to seek the chance to question him in person to probe his “mental processes” in taking the action. The Court planned to focus on that specifically as such questioning would be demanded of a “high-ranking Executive Branch official.”

The challengers would have used Ross’s answers to help prove that he was biased against Hispanics. Last October, the Supreme Court had temporarily barred such questioning while it reviewed the Administration’s objections to the questioning of the Cabinet officer.

That issue, however, appears not to be in the case any longer. Judge Furman explicitly based his decision solely on the evidence that the Administration itself had submitted in court in defending the plan to add the citizenship question. Thus, Ross’s personal testimony appears to be beside the point now.

The next move in the case thus is up to the Trump Administration. There is not enough time for an appeal to go through the normal court of appeals route, because the Census Bureau has said it needs to have the census questionnaire finalized by June of this year. Thus, the only option open to government lawyers would appear to ask the Justices to take on directly, bypassing the appeals court level, the question of its power to ask about citizenship.

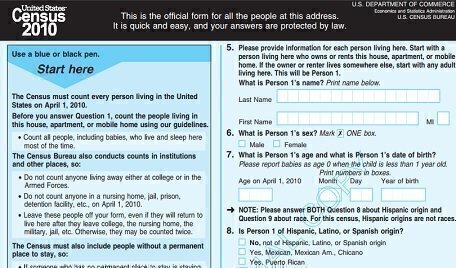

The census of the nation’s population is required by the Constitution, to occur every 10 years, and it is to count every person living in the country at the time of the count – whether or not they are citizens and whether or not they are in America illegally.

The actual count is used for two main purposes: first, to divide up the 435 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives according to each state’s population (although every state, however small its population, is guaranteed at least one House seat), and, second, the figures are the basis for allocating billions of dollars of federal funds to the states to pay for federal programs.

Judge Furman concluded that if the census form asked everyone to state their citizenship, the actual effect would be that “hundreds of thousands – if not millions – of people will go uncounted. The result will not only be a decrease in the quality of census data…but likely a net differential undercount…[of] people living in households containing noncitizens and Hispanics.”

Those challenging a citizenship question argued that non-citizens and Hispanics will not fill out the census form at all, because of fear that they or relatives would risk being deported.

The problem of under-counting, the judge decided, could not be cured by follow-up inquiries by census-takers. The Census Bureau’s own data from past countings, the judge said, showed that however extensive follow-up efforts might be, they do not overcome the decline in self-responses.

In ruling against Commerce Secretary Ross, Judge Furman said that his “most blatant” illegal act was ignoring and violating a specific federal law that data the Bureau seeks about the characteristics of the population must be obtained by means other than asking direct questions on the census form.

In addition, the ruling found that Ross had “ignored” or “cherry-picked” the evidence of the impact that would result from the addition of a question about citizenship. And, the opinion added, Ross had committed “a veritable smorgasbord of classic, clear-cut violations” of the federal law that governs how federal government agencies are to perform their duties.

Finally, the judge brusquely rejected the main reason that Ross and his aides had given as the rationale for adding the citizenship issue – that is, that it would gather data that the Justice Department needed to enforce federal voting rights laws. That, according to the judge, was a mere “pretext” that concealed the “true basis” of the decision.

The challengers had contended that the “true basis” of Ross’s action was his alleged bias against Hispanics, buttressed by claims that White House aides had pressed the Commerce Secretary to add the question in order to suppress the count of non-citizens and Hispanics. (When the challengers’ lawyers were allowed to question a Justice Department official who was in charge of voting rights law enforcement, that officials said the citizenship question was not needed for that purpose.)

While the judge said that Ross had acted out of that “pretext,” the opinion added that the judge could not find on the basis of evidence supplied by the government that Ross acted out of intentional racial prejudice.

The best evidence of the official’s real reason, the judge declared, would have been the direct, personal questioning of Ross under oath, but the Supreme Court had temporarily forbidden that while the trial went on.

Judge Furman completed the trial without any direct questioning of Ross, and then, on Monday, decided the key question without going beyond any evidence submitted by the Administration in the case.

The judge noted that his 277-page opinion was “long,” but remarked that there were many major issues affecting the census and added, wryly, that if he had had more time to prepare it, it would have been shorter.

Judge Furman was sharply critical of the tactics of Administration lawyers throughout the case. They had tried “no fewer than fourteen times” to halt the case altogether, and had also pursued multiple challenges to the way the case was being handled by the judge.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.