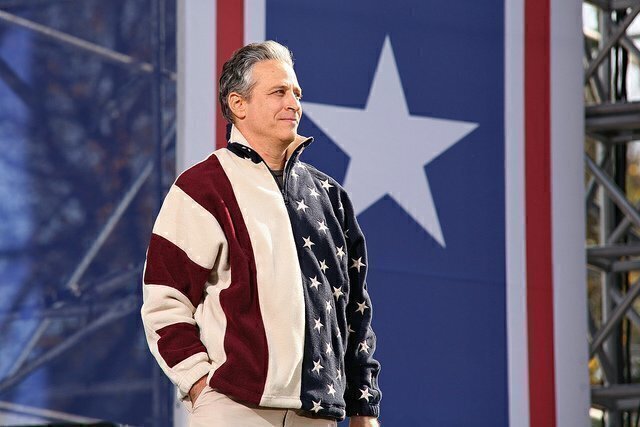

Over a career spanning three presidencies, Jon Stewart has brought biting political and social satire into the homes of millions. He feuded with Fox, bashed Bush, and embarrassed Obama. He championed the cause of veterans and asked Americans hard questions about their country. Whether it was punny titles, biting satire, or comedic relief, the Daily Show never failed to entertain. His departure is the end of an era.

However, Stewart’s work was just the latest act in a long history of American satire that stretches back to the colonial period. In fact, it was Philadelphia’s own Benjamin Franklin who introduced Americans to the wit and wisdom of Poor Richard. Franklin wrote the pamphlet, Rules by Which a Great Empire May Be Reduced to a Small One, belittling British colonial policy. The “Join or Die” cartoon was one of the earliest political editorial cartoons in America. Indeed, Franklin was so renowned for his wit that the other Founders refused to let him write the Declaration of Independence by himself for fear he would hide a joke in it.

Political satire endured in America through the antebellum period and beyond, with men like Ambrose Bierce ready to share a biting turn of phrase. “Bitter” Bierce was a 19th-century journalist who followed American armies in the Civil War. His views are embodied in his nickname and in quotes like, “War is God’s way of teaching Americans geography.” Bierce also wrote The Devil’s Dictionary, offering cynical definitions of everything from “conservative” to “youth.” He represents the cynicism and dark humor that took root during the Civil War in the face of untold horror on the front lines.

The Glided Age that followed was ripe for parody, with the phrase “Glided Age” itself a joke by Mark Twain. The era saw unprecedented political corruption, which spawned an abundance of political satire. New ideas and new social problems defined the period and proved to be fertile ground for American comedic expression.

One prominent master of the trade was Thomas Nast of Harper’s Weekly, who transformed the political cartoon from an elite political tool into a way to communicate with the illiterate and mold public perception. Nast’s exquisite artistic style turned Boss Tweed of Tammany Hall from a friendly politician providing for immigrants into a massive bully robbing the city and exploiting the poor. The cartoon campaign frightened Boss Tweed so much that he offered Nast $500,000 to “study in Europe.” Nast’s attacks cost Tammany Hall the 1871 elections and led to arrests of the Tweed ring, rendering Tweed a Caesar with a shattered sword.

Mark Twain’s own contributions can’t be underestimated; he is arguably the iconic dean of American literary satire. Twain used dark humor to illustrate the hypocrisy of the Antebellum South, mocking the racial and social restraints placed on society in works like Pudd’nhead Wilson. He toyed with his readers’ expectations and emotions in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, critiquing the society in which he grew up. He savaged his contemporaries, going after the nouveau riche and the post-war elites for their loose morals.

Twain also blended his politics and humor to spectacular effect in works like the War Prayer, mocking the imperialist ambitions sweeping the nation. To this day, his commentary remains a searing critique of American foreign policy. Still, it is probably his wit that will be most remembered by most Americans, with such gems as, “Suppose you were an idiot, and suppose you were a member of Congress; but I repeat myself.”

H.L. Mencken of The Baltimore Evening Sun added his own dose of cynicism to American media coverage in the 20th century. His reporting on the “Scopes Monkey Trial,” which he himself labelled as such, reveals his passion for fact and disdain for government.

The Sage of Baltimore’s cynical approach to the world made him an opponent of the Progressive movements sweeping the United States in the early 20th century. He mocked the stupidity of the common man, and attacked religious fundamentalism and religion in general. His caustic humor and satire owe much to Bierce and Twain. His distrust of government has made him a staple in American libertarian thought.

Nast paved the way for future political cartoonists to spotlight the darker side of American politics. He inspired men like Herbert Block, whose spectacular 90-year career included cartoons questioning everything from the Great Depression to the 2000 election. “Herblock” condemned atomic warfare with his character Mr. Atom; he pushed the United States to oppose fascism and fight against the Nazis’ march across Europe. Whatever the target, he used his pencil to promote the American values of equality and justice.

With the rise of television in the modern era, stand-up comedy has become a staple of American discourse. And there are few comedians more quintessentially American than George Carlin. For example, his famous bit “Seven Words You Can Never Say on Television” became the focal point of a Supreme Court case on indecency.

Carlin also explored the relationships between words in the English language, the idiosyncrasies of everyday life, and the injustices of the modern world. His targets spanned the political spectrum, condemned for their hypocrisy in everything from abortion to economics. And Carlin’s distrust of religion and government echoed the beliefs of Mencken decades earlier. His prolific career left an indelible stamp on American comedy and carried its traditions into the present day.

American satirists have come in many forms over the years, but they share a common theme: they believe that America can be better than it is now. They work to hold up a mirror to our world, reminding us of all the challenges we would rather forget. They contest the foundations of our society, and they push for a constant reexamination of our ideals. They lead us, inform us, and mock us, in that peculiarly American way.

Jon Stewart is yet another manifestation of American wit, putting into words and pictures our discontent with the world. He has, for sixteen years, held up that mirror. Now, he is putting it aside. But he has left us many heirs to tweak our noses and ask the hard questions. There will always be someone to raise up that mirror, to mock what is there in the name of something better.

Louis Gentilucci is an intern at the National Constitution Center.