In the space of about three hours on Monday, the intense, months-long battle over partisan gerrymandering in Pennsylvania elections this year for 18 members of the U.S. House of Representatives reached a pause, one that may well end it altogether.

A brief ruling by the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., and a 24-page decision by a federal trial court in Harrisburg, PA, rebuffed at least temporarily the efforts of Pennsylvania Republican leaders to keep the dominant role in elections for House members from the Keystone State. The GOP had repeatedly won 13 out of those 18 seats, leaving only five for Democrats – a pattern that had prevailed in every congressional election since 2011.

A brief ruling by the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., and a 24-page decision by a federal trial court in Harrisburg, PA, rebuffed at least temporarily the efforts of Pennsylvania Republican leaders to keep the dominant role in elections for House members from the Keystone State. The GOP had repeatedly won 13 out of those 18 seats, leaving only five for Democrats – a pattern that had prevailed in every congressional election since 2011.

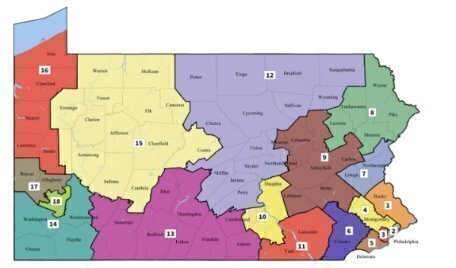

In place of the districting map that produced all of those GOP victories will be one that experts say will likely allow Democrats to win at least three more of the seats, and that might even result in a nine-to-nine split as a result of the general election on November 6, depending on turnout and intensity of Democratic campaigning. Even a modest gain of seats in Pennsylvania could be a significant factor in helping the Democrats regain control of the House of Representatives, if recent election results favorable to Democrats continue this fall.

The new map was made public on February 19 after being drawn up by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, by a 4-to-3 split vote. The court stepped in to craft its own version of House district lines after a ruling in January striking down the 2011 plan as a partisan gerrymander, which it found to be a violation of the Pennsylvania state constitution’s promise of “free and equal” elections. When district lines are drawn with the specific aim of giving one political party an advantage over the other and that actually happens, it dilutes the votes of members of the disfavored party, it said, and that is forbidden by the state constitution.

After the two court rulings on Monday afternoon, coming in a rapid succession that suggested they may well have been coordinated, at least to a degree, the electoral situation in Pennsylvania is now this: candidates will file their completed nominating petitions this week, with the deadline for seeking voter signatures occurring on Tuesday, and final rules will be set by state officials for holding a primary House election on May 15. The candidates chosen in the 18 districts will compete in the general election come November.

While that political situation appears settled, what also got settled on Monday – at least for the time being – was that a combined group of 12 judges on federal benches had avoided a major constitutional clash between the Pennsylvania Supreme Court and those 12 judges’ courts – the Supreme Court in Washington, and the trial court in Harrisburg.

The Supreme Court did not explain its one-sentence order, turning down a plea by the state’s two top GOP legislative leaders to block the use of the court-drawn map that replaces the 2011 map. And, since no dissents were recorded to that brief order, the appearance at least was that the nine Justices could have been unanimous even if one or more members of the Court would have preferred to vote for the GOP challenge. Justices do not always publicly reveal it when they dissent when such brief, procedural orders emerge.

In Harrisburg, the three judges on the U.S. District Court definitely were unanimous, and they ruled in a way that barred other GOP leaders in Pennsylvania – two state senators and eight current House members – from even trying to salvage their challenge to the state court’s version of the districting.

Is any legal option left open to the state’s Republican leadership to try, however unpromising it might be? They could file an appeal at the Supreme Court to protest the Harrisburg court’s decision, and they could go ahead with an earlier plan to file a formal appeal at the Supreme Court to challenge directly the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s actions. Neither of those alternatives appeared to have much chance of succeeding, partly because of the way the Supreme Court rebuffed the request to block the state court’s map.

Plus, the fact that state officials are moving along with actual preparations for the May 15 primary election for House candidates could mean that any later effort by the GOP almost certainly would lead to confusion and maybe even chaos in the campaign in the state.

About the only genuine mystery remaining as of Monday, in the wake of the two courts’ rulings, was why the Supreme Court had taken 13 days to decide what to do with the GOP legislative leaders’ challenge. This was those lawmakers’ second challenge in this dispute, and the earlier one had been denied swiftly by Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., who acted without even sharing the question with his eight colleagues. This time, Alito passed along the issue, sharing it with the other Justices. It would have taken five votes on the full Court to grant the delay.

Because the Supreme Court had remained totally silent this time, for almost two full weeks, it has appeared that the Justices either were having difficulty making up their minds, or were waiting for something to happen elsewhere. The brevity of the order that did emerge on Monday afternoon hinted strongly that the Justices had had no trouble making up their minds – or at least not enough trouble for them to bring it out into the open with a divided outcome.

The fact that less than three hours passed between the release of the ruling by the Harrisburg court and then the release of the Supreme Court’s order gave at least some support to speculation that the Justices had wanted the lower court to act first, so as not to influence how it judged the case pending in Harrisburg – especially since both cases in the two courts involved the very same questions under the federal Constitution’s Elections Clause.

The questions were: did that Clause bar the state Supreme Court from drawing its own map using criteria that it had just spelled out for the first time, and did that Clause require the state court to give the legislature sufficient time to come up on its own with a replacement map?

Curiously, perhaps, neither of the two court rulings Monday settled those questions. The court in Harrisburg ruled that the challengers simply had not proved that they had a right even to file their lawsuit in federal court, because the GOP leaders and House members could not show that they would be harmed by the use of the state court’s map. Without their having a right to sue, the federal court there had no jurisdiction to decide the Elections Clause questions, it said, even though it remarked that those questions were of real importance to the nation and to Pennsylvania.

In the Supreme Court’s order, the only actual action was to deny a request for a delay of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision and the use of its version of the map pending the filing later of a formal appeal. That request, though confined to the issue of a temporary delay, relied upon the claim that the state court had violated the Elections Clause in the two ways the GOP lawmakers had said, so the use of the state court map should be barred for the time being pending an appeal.

While one issue the Justices consider when they are faced with such a request for delay is whether there is a good chance that the later appeal would actually succeed, the fact that they chose to deny a delay suggested that there was no perceived chance of the appeal succeeding later. And that was at least an implied suggestion that the Elections Clause challenge was not a strong one.

The Pennsylvania congressional election saga has been unfolding since last June, when the 2011 districting plan was first challenged in state court. It has been examined in three separate cases in federal court, along with the review by state courts in that first lawsuit.

And the saga played out against a background of growing debate across the nation about partisan gerrymandering of elected bodies, including the House of Representatives and state legislatures. That controversy already was under review in the Supreme Court during the current term, in a case involving a claimed partisan gerrymander in the Wisconsin state legislature and a similar claim involving one House district in Maryland.

Given the intensity of the controversy in recent months, it is perhaps an irony that the Supreme Court has never spelled out what the constitutional rules for judging whether partisan gerrymandering has occurred. That is exactly the challenge the Justices face in the Wisconsin and Maryland cases. The Justices heard the Wisconsin case in October, but have not yet ruled; they will hold a hearing on March 28 in the Maryland case.

The issue of what the federal Constitution might require to make a partisan gerrymander invalid was not an issue in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court decision, since that ruling was based entirely on an interpretation of the state constitution.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011 and has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com.