The current case involving Mahmoud Khalil, a Columbia University student facing expulsion from the United States for his participation in public pro-Palestine protests, may center on a law from the McCarthy era, and how courts interpret it.

On March 8, 2025, federal immigration officers detained Khalil at his university-owned apartment in New York. Agents reportedly told Khalil that his legal permanent resident status had been revoked by the State Department. On March 10, a federal judge ordered a temporary pause to Khalil’s deportation process, with a hearing set for March 12.

On March 8, 2025, federal immigration officers detained Khalil at his university-owned apartment in New York. Agents reportedly told Khalil that his legal permanent resident status had been revoked by the State Department. On March 10, a federal judge ordered a temporary pause to Khalil’s deportation process, with a hearing set for March 12.

In a public statement posted on X, Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin said, “Khalil led activities aligned to Hamas, a designated terrorist organization. ICE and the Department of State are committed to enforcing President Trump’s executive orders and to protecting U.S. national security.”

President Donald Trump also claimed on his social media channel Truth Social that many protestors “are not students, they are paid agitators. We will find, apprehend, and deport these terrorist sympathizers from our country – never to return again. If you support terrorism, including the slaughtering of innocent men, women, and children, your presence is contrary to our national and foreign policy interests, and you are not welcome here.”

Khalil’s attorney, Amy Greer, in a statement said that Khalil “was chosen as an example to stifle entirely lawful dissent in violation of the First Amendment.”

Immigration and Naturalization Law

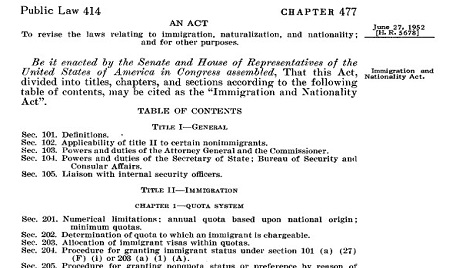

In a notice to appear document published by The Washington Post on Wednesday, the government argues it has the power to revoke Khalil’s legal permanent resident status under the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 (or INA). Also known as the McCarran-Walter Act, the INA combined various immigration laws and provisions into one act and barred immigrants to the United States who advocated “the economic, international, and governmental doctrines of world communism.” President Harry Truman vetoed the McCarran-Walter Act, but Congress overrode the veto. The act has been amended many times since then, including a significant revision in 1965.

The federal government has the authority to decide who becomes a citizen or resides in the United States. Congress set the first basic immigration requirement in 1790, which required a two-year residency in the United States for those who sought citizenship.

Congress and the executive branch work together on matters of immigration policy and enforcement. Although there is no explicit mention of immigration policy in the Constitution, a series of Supreme Court decisions has established that the political branches of the federal government—Congress and the president—share responsibility for immigration. In many cases, Congress passes immigration laws enforced by the executive branch; in other cases, the executive branch has prosecutorial discretion to implement immigration policies.

Several provisions from the INA may likely come into play in the Khalil case. One section of the law says that “An alien whose presence or activities in the United States the Secretary of State has reasonable ground to believe would have potentially serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States is deportable.” In the notice to appear document, Secretary of State Marco Rubio determined that Khalil’s presence or activities in the United States “would have serious adverse foreign policy consequences for the United States.”

The INA also has an exemption that prohibits an alien’s removal “because of the alien’s past, current, or expected beliefs, statements, or associations, if such beliefs, statements, or associations would be lawful within the United States.” But the law allows the government to proceed with a deportation if the Secretary of State “personally determines that the alien’s admission would compromise a compelling United States foreign policy interest.” This part of the INA was not cited in the notice to appear document.

The First Amendment in Play

Critics of Khalil’s potential deportation have argued that the State Department lacks the authority to deport Khalil under the First Amendment’s Free Speech Clause and Assembly and Petition Clause.

The First Amendment states that, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE), in a letter to the State Department and other agencies, has said “the federal government must not use immigration enforcement to punish and filter out ideas disfavored by the administration.” It also questioned if Khalil’s due process rights were violated.

The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University, in a statement, believed that “arresting and threatening to deport students because of their participation in political protest is the kind of action one ordinarily associates with the world’s most repressive regimes.”

Legal scholar Steve Vladeck wrote about several possible scenarios as the Khalil deportation case unfolds, once the government makes its case in federal court. One factor is whether the federal court case is heard in New York, or in Louisiana (where Khalil was sent after his detainment). The other factors are related to how strong the executive branch’s case is under the powers granted to it by the INA, weighed against First Amendment considerations.

On March 12, Khalili’s lawyers appeared in court, and they will be permitted to speak with Khalil, who is at a detention center in Louisiana. The government has asked for Khalili’s case to be heard in Louisiana or New Jersey.

The outcome of the case may make clear how much the Immigration Act of 1952 will come into play in deciding the constitutionality of Khalil’s deportation and other similar actions taken by the State Department and Homeland Security.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.