On May 24, 1937, the Supreme Court decided in two separate but related cases that the Social Security Act of 1935 was constitutional. In Steward Machine Co. v. Davis and Helvering v. Davis, the Court upheld the Act as a proper use of the spending power.

The Court’s March 1937 decision in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish upholding Washington’s minimum wage statute has been most often connected to the “switch in time” whereby the Court’s majority began upholding New Deal legislation under threat of court-packing from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Shortly after that decision came out, Steward Machine Co. v. Davis and Helvering v. Davis saw the Court continue to uphold broad national power—this time, to tax employers to pay for benefits under the act and for Congress to use its spending power to push states to pass laws to fund unemployment compensation.

The Court’s March 1937 decision in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish upholding Washington’s minimum wage statute has been most often connected to the “switch in time” whereby the Court’s majority began upholding New Deal legislation under threat of court-packing from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Shortly after that decision came out, Steward Machine Co. v. Davis and Helvering v. Davis saw the Court continue to uphold broad national power—this time, to tax employers to pay for benefits under the act and for Congress to use its spending power to push states to pass laws to fund unemployment compensation.

In Steward, an Alabama corporation paid the tax required under the statute before filing a claim for refund with the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, claiming it could recover the payment because the statute was unconstitutional. It argued the tax was not an excise, it was not uniform throughout the United States, its exceptions were numerous and arbitrary in violation of the Fifth Amendment. Also, the corporation said the law’s purpose was regulatory and not for revenue, and constituted an unlawful invasion into the reserved powers of the states.

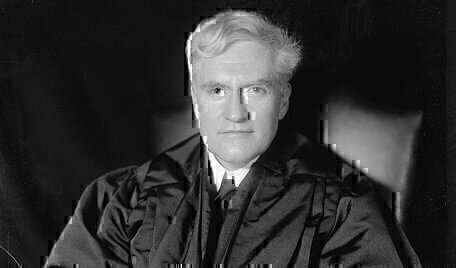

Justice Benjamin Cardozo wrote the Court’s majority opinion, determining that the power of Congress to tax was as extensive as the plenary power of states to tax. Congress could tax not only state-created corporations, but also the transmission of property by inheritance under state law. The Court decided the federal government, no different than states, could treat some businesses different from others for tax purposes and any considerations of policy and practical convenience would not be condemned by the Court as arbitrary. Finally, Cardozo declared the act did not violate the 10th Amendment because under the Act, the national government only induced states through the “spending clause” to pass laws regarding unemployment compensation. Congress did not improperly coerce states but acted during “a crisis so extreme, the use of the moneys of the nation to relieve the unemployed and their dependents is a use for any purpose narrower than the promotion of the general welfare.”

Helvering focused on Title II of the Social Security Act, which authorized grants of money for “Old Age Benefits” in order to assist states in the administration of their unemployment compensation laws. It was the product of a suit by a shareholder of the Edison Electric Illuminating Company, asking for the company to be enjoined from making payments under the law because the taxes on the employer and the employees were unconstitutional.

Again, Cardozo wrote the majority in a 7-2 decision, upholding the Social Security Act as a proper use of the spending power for the “general welfare”— and in this case, Justice George Sutherland did not dissent. Cardozo stated:

“Congress may spend money in aid of the ‘general welfare’ . . . There have been great statesmen in our history who have stood for other views (Madison, Story, Hamilton) . . . The line must still be drawn between one welfare and another, between particular and general. Where this shall be placed cannot be known through a formula in advance of the event ... The discretion belongs to Congress, unless the choice is clearly wrong, a display of arbitrary power, not an exercise of judgment.”

Cardozo made heavy use of the evidence presented by Congress in favor of the legislation. The President’s Committee on Economic Security had conducted an investigation and issued a report, finding that in 1930, 71 out of 224 factories had fixed maximum hiring age limits, with the majority under 46. The Court would not judge the wisdom of the scheme Congress had chosen to deal with a national crisis when states were unwilling or unable to act.

The Court, therefore, decided that the Old Age Benefits scheme of Title II and the Title VII tax on employees did not violate the 10th Amendment. Once again invoking the Great Depression, Cardozo noted that the “purge of nationwide calamity that began in 1929 has taught us many lessons. Not the least is the solidarity of interests that may once have seemed to be divided. Unemployment spreads from State to State, the hinterland now settled that, in pioneer days gave an avenue of escape.”

The Court, reflecting upon a crisis which fundamentally changed society, openly considered in both these cases how the Great Depression may well have also changed the Constitution and the power of Congress to spend to aid the general welfare of the American people. More recent cases have made clear the extent of Congress’s spending powers. In the 1987 case, South Dakota v. Dole, the Court decided that so long as Congress did not impose unconstitutional or coercive conditions and the spending promoted the “general welfare,” Congress could attach reasonable and unambiguous conditions to funding given to states as part of a national program. In the “Obamacare” case, NFIB v. Sebelius in 2012, Chief Justice John G. Roberts found that Congress may offer the states grants and require the states to comply with accompanying conditions, but there must be a genuine choice whether to accept the offer.

Nicholas Mosvick was a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.