After the events of January 6, 2021, the Constitution’s 25th Amendment was back in the news, in the wake of Wednesday’s violence at the U.S. Capitol and allegations that President Trump played a role in it. Here is a brief overview of how the amendment works, in a situation where a president is unable to perform his duties.

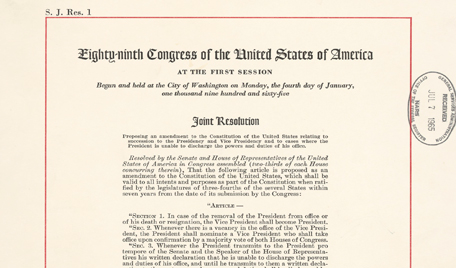

In short, the 25th Amendment details the procedure that governs questions of presidential (and vice-presidential) succession and disability. After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Congress passed the 25th Amendment in July 1965 after a considerable public debate in the House and Senate. Three-quarter of the states ratified the amendment in February 1967.

In short, the 25th Amendment details the procedure that governs questions of presidential (and vice-presidential) succession and disability. After the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, Congress passed the 25th Amendment in July 1965 after a considerable public debate in the House and Senate. Three-quarter of the states ratified the amendment in February 1967.

Concerns about who acts as president if a president’s health is in danger were raised during the Eisenhower administration after the president suffered a serious heart attack. Also, the Constitution as first written and ratified did not deal clearly with who succeeds the president when the office becomes vacant, or who acts as president when the chief executive is unable to perform the job for various reasons.

The 25th Amendment’s first two sections expand on Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution. They make it clear the vice president becomes president “in case of the removal of the President from office or of his death or resignation.” They also include important features that allow the president and Congress to nominate and approved a new vice president when that office became vacant, and to establish a line of succession if the president and vice president are not in office and those offices are vacant.

The 25th Amendment’s third and fourth sections deal with scenarios where a president may suffer from or be judged to have an “inability” or a “disability.” Scares about the president’s physical health go back to the first president, George Washington, who fought pneumonia in 1790. Woodrow Wilson and Grover Cleveland had serious health problems while in office. James Garfield was incapacitated for months after he was shot by an assassin and later died in office. Franklin Pierce, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Dwight D. Eisenhower also struggled with health issues.

Link: Read The Full Text

The 25th Amendment’s Section 3 deals with the president’s voluntary transfer of power and allows the president to notify Congress that he has designated the vice president to act as president until the president is able to resume work. This has happened briefly in three instances after 1967 when Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush told Congress the vice president would be acting as president while they were under general anesthesia for medical procedures.

Section 4 is the most controversial part of the 25th Amendment: It permits the vice president and either the Cabinet or a body approved “by law” formed by Congress, to jointly agree that “the President is unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office.” In theory, this clause was designed to deal with a situation where an incapacitated president could not tell Congress that the vice president needed to act on his behalf. It has never been invoked yet.

The most recent guidance from the Congressional Research Service identifies the amendment’s potential use. The report from 2018 includes concepts discussed during the congressional debates about the 25th Amendment in the 1960s.

The CRS says a majority of current or acting heads of 15 cabinet positions would need to agree with the vice president to invoke the 25th Amendment. The other potential actor, a disability review panel, would need to be established by a statute that is signed by the president, or if vetoed, approved by two-thirds of the House and Senate. That panel is not currently established.

Senator Birch Bayh, who played a critical role in championing the 25th Amendment, explained in February 1965 that Section 4 was designed to deal with “an impairment of the President’s faculties, meaning that he is unable either to make or communicate his decisions as to his own competency to execute the powers and duties of his office.”

Another 25th Amendment author, Rep. Richard Poff, identified two examples in April 1965 where Section 4 could be invoked. “One is the case where the President by reason of some physical ailment or sudden accident is unconscious or paralyzed and therefore unable to make or to communicate the decision to relinquish the powers of his Office. The other is the case when the President, by reason of mental debility, is unable or unwilling to make any rational decision, including particularly the decision to stand aside.”

Regardless of the reason to invoke the 25th Amendment, Congress set a high bar to allow its use. Once the vice president and either the Cabinet or a body approved by Congress agree to invoke the amendment, the vice president is allowed immediately to “assume the powers and duties of the office as Acting President.” The president can notify Congress that “no inability exists” and he “shall resume the powers and duties of his office” unless the vice president and the Cabinet or body formed by Congress jointly object.

If not in session, Congress is required to convene within 48 hours once the 25th Amendment is invoked. When in session, Congress has 21 days to settle the question if the president notifies Congress in writing that no inability exists. The vice president and the Cabinet or disability body have four days to file an objection to the president’s declaration within that 21-day time frame. If no objection is filed, the president resumes his duties. If the president’s declaration is contested, two-thirds of the House and Senate must agree to allow the vice president to act as president until the president is considered able to serve, and the president can file another declaration about his ability to serve after Congress votes on the question.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.