It’s a sad day for some historically minded Philadelphians: It's the anniversary of the congressional act that moved the nation’s capital from their city to Washington, D.C.

The Residence Act of July 16, 1790, put the nation's capital in current-day Washington as part of a plan to appease pro-slavery states who feared a northern capital as being too sympathetic to abolitionists.

The Residence Act of July 16, 1790, put the nation's capital in current-day Washington as part of a plan to appease pro-slavery states who feared a northern capital as being too sympathetic to abolitionists.

The City of Brotherly Love became the ex-capital for several reasons: the machinations of Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson; the compromise over slavery; a concern about public health; and a grudge against the Pennsylvania state government were all factors in the move.

The problems started with some rowdy actions in 1783 by Continental soldiers. Until then, Philadelphia had been the new nation's hub. Important decisions were made there, and it was equally accessible from the North and the South.

The Continental Congress was meeting in Philadelphia in June 1783 at what we now call Independence Hall, operating under the Articles of Confederation. However, there were problems afoot. The federal government had issues paying the soldiers who fought in the war against the British for their service.

The Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 was a crisis that forced the Congress to focus on its safety and pitted the federal government (in its weakened form) against the state of Pennsylvania.

Unpaid federal troops from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, marched to Philadelphia to meet with their brothers-in-arms. A group of about 400 soldiers then proceeded to Congress, blocked the doors to the building, and demanded their money. They also controlled some weapons storage areas.

Congress sent out one of its youngest, quick-talking delegates to negotiate with the troops: Alexander Hamilton, a former soldier. Hamilton convinced the soldiers to free Congress so the lawmakers could meet quickly and reach a deal about repaying the troops.

Hamilton did meet with a small committee that night, and they sent a secret note to Pennsylvania’s state government asking for its state militia for protection from the federal troops. Representatives from Congress met with John Dickinson, the head of Pennsylvania’s government; Dickinson discussed the matter with the militia, and he told Congress Pennsylvania wouldn’t use the state’s troops to protect the federal lawmakers.

On the same day, Congress sneaked away from Philadelphia to Princeton, New Jersey. It traveled to various cities over the following years, including Trenton, New Jersey; Annapolis, Maryland; and New York City.

Delegates agreed to return to Philadelphia in 1787 to draw up the current U.S. Constitution, while the Congress of the Confederation was still seated in New York City. Part of the new Constitution addressed the concerns caused by the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783.

Article I, Section 8 gave Congress the power to create a federal district to “become the Seat of the Government of the United States, and to exercise like Authority over all Places purchased by the Consent of the Legislature of the State in which the Same shall be, for the Erection of Forts, Magazines, Arsenals, dock-Yards, and other needful buildings."

When Congress met in 1789, two locations were proposed for the capital: one near Lancaster and another in Germantown, an area just outside Philadelphia.

However, Hamilton became part of a grand bargain to move the capital to an undeveloped area that encompassed parts of Virginia and Maryland, receiving some help from Thomas Jefferson along the way.

A deal had been reached between Hamilton, James Madison, and Jefferson a month earlier, where Hamilton agreed with the idea that the capital would be moved to the South. In exchange, Hamilton got a commitment to reorganize the federal government’s finances by getting the southern states to indirectly pay off the war debts of the northern states.

The Residence Act put the capital in current-day Washington. Hamilton’s Assumption Bill passed 10 days later after Congressional members from the Potomac region switched their votes.

But a twist in the deal was negotiated by Robert Morris: Until the new capital was built on the Potomac, the capital would be in Philadelphia for 10 years, giving the Pennsylvanians a chance to convince Congress that life was better there than in an undeveloped region of the Potomac.

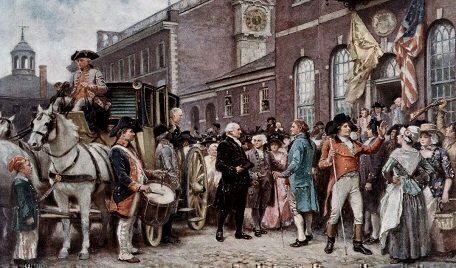

During the following decade, Philadelphians lobbied hard for the capital to stay in Pennsylvania. They offered President Washington an elaborate mansion as an incentive to stay. Instead, he and his successor, John Adams, lived in a more modest house in Philadelphia near Congress.

Also, a yellow fever epidemic hit Philadelphia in 1793, raising doubts about the safety of the area. And native Virginians like Washington, Madison, and Jefferson were actively planning for a capital near their home.

So on May 15, 1800, Congress ended its business in Philadelphia and started the move to the new Federal District. President Adams also left Philadelphia in April and moved into the White House in November.

Philadelphia ceased to officially be the nation’s capital on June 11, 1800.