Lyle Denniston, Constitution Daily's Supreme Court correspondent, looks at the unique role of the Federal Bureau of Investigation's director and the President's ability to remove the director if warranted.

For much of the 108-year history of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, it had only one director – J. Edgar Hoover, who led the agency for a few days short of 48 years. He was as near to a truly independent official in the federal government’s Executive Branch as the Constitution allows. He had his own special relationship with Congress, and ran the Bureau much as he wished.

His successors have not been as powerful, nor as independent. Indeed, one director in the Bureau’s history – former federal judge William S. Sessions – was fired for ethical reasons by President Bill Clinton in the summer of 1993, a little more than halfway through a 10-year appointment. The President’s public explanation was that there had been a loss of confidence in Sessions’ leadership. Then-Attorney General Janet Reno recommended the dismissal.

It is sometimes assumed that the President can oust an FBI director only “for cause” – that is, for some misconduct in office. But, as a Congressional Research Service study of the director’s office pointed out two years ago, “there are no statutory conditions on the President’s authority to remove the FBI director.”

The constitutional reality is that, if a government official is clearly placed within the Executive Branch, that official serves at the pleasure of the President, and can be fired “at will.” That history has had a recent illustration: earlier this month, the federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., struck down part of a law by which Congress created a single director to lead the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau – a law that specified that the director could be removed by the President only “for cause.”

The appeals court simply deleted that phrase from the law, thus making the agency’s head subject to being fired by the President for any reason, or no reason at all. (The government has not yet indicated whether it will challenge that ruling in further appeals, perhaps to the Supreme Court.)

That is very much in line with what the Supreme Court has ruled over the years, to preserve the power of the President to be fully in charge of the Executive Branch. Since 1968, a federal law has provided that the head of the FBI will have a 10-year term in office. But the situation legally is that the chance to serve a full term depends upon retaining the confidence of the President.

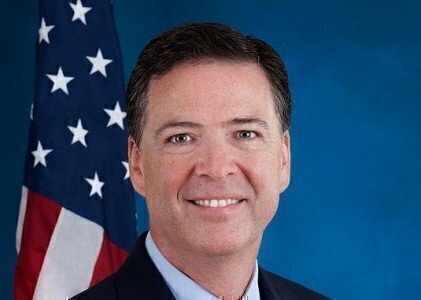

This constitutional issue has arisen anew in the wake of the controversy over FBI Director James B. Comey’s decision last Friday to notify Congress that the FBI was examining a new batch of e-mails that might be linked to the official investigation into Hillary Clinton’s use of a private e-mail server while Secretary of State.

Comey, named to the post by President Obama just over three years ago, has publicly defended his action by saying he had promised to keep Congress up to date on the status of the investigation. While the director’s action has stirred up a major public relations battle over its impact on the presidential election campaign, the White House has so far not joined in that controversy.

On Sunday, the Senate’s leader of the Democratic minority, Sen. Harry Reid of Nevada, released a letter he had written to Comey. The letter said flatly that Reid’s office “has determined that these actions may violate the Hatch Act, which bars FBI officials from using their official authority to influence an election.” Accusing the director of “partisan actions,” the letter said that “you may have broken the law.”

On Saturday, Richard W. Painter, a law professor at the University of Minnesota who served as President George W. Bush’s White House ethics lawyer for two and a half years, filed formal complaints against Comey with two government agencies that investigate political activity or potential misconduct by government employees. Explaining his action in an opinion piece published on Sunday on the website of The New York Times, Painter wrote: “I never thought that the FBI could be dragged into a political circus surrounding one of its investigations. Until this week.”

In Comey’s earlier public statements about the e-mail investigation, he said he had not cleared those statements with anyone else in the Justice Department (of which the FBI is a part) or anyone elsewhere in the government. News stories since Friday have said that some of Comey’s aides did share his plan to write to Congress about the newly-discovered e-mails with Department officials, some of whom reportedly argued against it, but there apparently was no order not to go forward with it.

The FBI has a very positive image with much of the American public, and that has always supported its authority. Even though a director is subject to being dismissed at the President’s choice, it has always been apparent that there are political risks in doing so. When the FBI director was fired in 1993, President Clinton felt obliged to order a full investigation of complaints and waited for a recommendation from Attorney General Reno.

Director Sessions’ dismissal did draw protests from some members of Congress, but the lawmakers took no action to block the appointment of a successor after the firing.

Under the 1968 law that for the first time required Senate approval of a new FBI director’s appointment by the President, any director is restricted to serving only a single term of 10 years, unless Congress passes specific new legislation to keep the director on the job. That has happened only once under the 1968 law, in 2011, when Congress passed a law to allow Robert S. Mueller a second term specifically limited to two years.

Aside from being subject to removal by a President, the FBI director, like all “civil officers of the United States,” can be ousted from office if charged with “high crimes and misdemeanors” by the House of Representatives and removed by a two-thirds vote of the Senate.

The Constitution does not define what “high crimes and misdemeanors” can lead to impeachment, but it has become clear from historical practice that this depends entirely on what the House believes would qualify.

Legendary journalist Lyle Denniston is Constitution Daily’s Supreme Court correspondent. Denniston has written for us as a contributor since June 2011 and he has covered the Supreme Court since 1958. His work also appears on lyldenlawnews.com.