On Monday morning, a crowd – no one knows for sure how big it will be – will gather at a church in Phoenix to start a three-day, 38-mile hike to visit sites symbolic in the history of Arizona women. The distance of the event is itself a symbol: 38 is the number of states it will take to ratify the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The aim of the hike, a project of a coalition of liberal political action groups under the banner of “AZ Resist!”, is to put pressure on the state legislature to make Arizona the 38th ratifying state to satisfy Article V of the Constitution.

The aim of the hike, a project of a coalition of liberal political action groups under the banner of “AZ Resist!”, is to put pressure on the state legislature to make Arizona the 38th ratifying state to satisfy Article V of the Constitution.

After stops at the home of retired Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, the first woman named to the Court (and a former state legislator and judge), then at the office of the state’s first Arizona woman elected to the U.S. Senate -- the new Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, and other sites, the walk will end on Wednesday at the state capitol, where the state legislature will be in session until late April.

“AZ Resist!” recruited women to come out in support of sex equality in the Constitution, asserting that the only right women have, as women, under the basic document is the right to vote (assured when the 19th Amendment was added in 1920). “It’s far past time that women be added to the United States Constitution with equal rights,” the coalition said.

The Supreme Court actually has extended a measure of equality to women’s rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment and one clause under the Fifth Amendment, but that protection is not as sturdy as is the Constitution’s guarantee of equality based on race. ERA, though, very likely would put women under a legal shelter equal to what now exists for racial minorities.

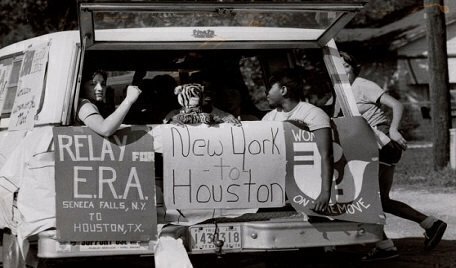

On ERA, “Just one more state!” has become a call to new activism among women’s rights activists. Based on ratifying votes in 37 states (some of which may be in doubt), activists are trying to press on to a successful conclusion a campaign that began more than 86 years ago, when the first proposed ERA was introduced in Congress, in December 1923.

Even if Arizona’s legislature were to vote to ratify, however, the path of the ERA toward actual addition to the Constitution is strewn with potential obstacles – political, legal, even constitutional. Resolving much controversy would be a historic task, and it is not even clear under Article V and from the lessons of constitutional history what part of government would have the last word.

The Supreme Court once took on the task of answering some of those questions in 1982, but backed off from deciding four test cases after a Justice Department lawyer had advised the Justices that the version of ERA that had been pending in the states since 1972 “has failed of adoption no matter what the resolution of the legal issues presented.” The Court, in ordering those cases dismissed, acted as if that version of ERA were officially dead.

Among some of the toughest issues surrounding ERA’s fate at this point in history, none is more important than this basic question: Is working for a 38th state to ratify the version of the ERA that earlier “failed of adoption” the best strategy, or should the advocates start all over with a fresh new version, as recently introduced in the new Congress?

Within that strategic choice lie other core questions:

First, if leaders of Congress who are sympathetic to ERA do attempt to make a fresh start, is there any realistic chance that it could get the minimum two-thirds vote of approval in both the House and in the Senate, even if the idea had great popularity and would stand a good chance of ratification in three-fourths of the states if it were sent to them by Congress?

Second, for those advocates moving on with the “just one more state” strategy, as in Arizona right now, can they be sure that their state legislature – or any other -- can legally add its ratification?

And that question has a number of other issues embedded in it: Since the back-to-back periods that Congress had set up for ratification by the states expired in 1982, is that version of ERA still alive, after all? Could Congress open a new ratification period (and what vote majorities would that require in both houses to do so)? If Congress did so, who would judge whether it was legal or constitutional?

Third, is it really true that 37 state legislatures have actually ratified that version of ERA? Counted among the total of 37 are Nevada (No. 36) and Illinois (No. 37), where the legislatures gave approval in 2017 and 2018 – years after the periods of ratification set up for the earlier ERA had expired. Who decides if those ratifications were valid?

Fourth, what difference does it make to the total of 37 that it includes five states that, after initially ratifying the earlier version of ERA, changed their minds later and withdrew their approvals? Those are Nebraska, which rescinded in 1973; Tennessee, in 1974; Idaho, in 1977; Kentucky, in 1978, and South Dakota, 1979. Does it make any difference that they did so while the designated ratification period was still open? And who decides whether they had a legal right to switch – that is, is ratification a one-way ratchet?

Fifth, does it make any difference now to the fate of the earlier version of ERA that one amendment to the Constitution – the 27th Amendment (putting a limit on when members of the House and Senate could raise their salaries) – was ratified after pending before the states without an approval deadline for a total of 203 years before it finally was ratified? (It was part of the list that James Madison wrote in his version of the original Bill of Rights; that list was sent to the states in 1789, but the congressional pay article did not gain ratification until 1992.)

Sixth, it is far from clear – primarily because the Supreme Court had taken various positions on it over the years – whether disputes over constitutional amendments are “political questions” to be answered by Congress, or judicial issues to be resolved by the courts, ultimately the Supreme Court, or shared between those two branches? (The Constitution provides no role in the amendment process for the third national government branch, the President.)

Finally, it is far from clear, if such disputes do go into the courts, who has the legal right to file a lawsuit to get those controversies resolved. In other words, who can satisfy the requirement of Article I that a disagreement can be taken to federal court only if it amounts to a genuine “case or controversy”?

With so many important questions hanging over today’s pro-ERA campaign, does that mean that the reinvigorated cause is doomed? Not necessarily. Most of those questions have remained abstract since the expiration of the ratification period 37 years ago – as illustrated by the Supreme Court stepping aside in 1982. But most of the questions would leap into reality, if Arizona or some other state were now to ratify, leading proponents to claim that there were now 38 and seek an official declaration of ratification.

Those pursuing the “just one more state” strategy obviously are assuming that none of the five rescissions counts, but that the two new ratifications in 2017 and 2018 do count. Congress or the courts would have to rule on those assumptions.

In Congress, the process would probably involve a request to pass a resolution declaring ERA as ratified. In the courts, the process would probably begin with a lawsuit in a federal trial court, seeking a “declaratory judgment” that ratification had been achieved.

That’s the legal side of ERA’s prospects now. The political world has no doubt undergone change, even radical change, since 1982, and that has actually changed the nature of the controversy over the attempt to revive ERA.

One of the most persistent arguments made before by opponents of ERA was that it would mean that women would be drafted into the military, and die in combat. Now, there is no role in the American military, in combat or otherwise, that remains closed to women. (Indeed, a federal judge recently ruled that the registration for the draft – which still exists as a potential way to raise troops – is an unconstitutional form of sex discrimination under existing legal principles.)

Another of the core challenges to ERA was that it would foster homosexual equality, even encouraging same-sex marriage. But equality for gays, lesbians and bisexual individuals has undergone its own constitutional and legal revolution, with enormous success even in the Supreme Court.

If those two arguments against ERA have lost force, another new cultural shift has added a religious dimension to the entire field of sex and gender discrimination, and that is giving rise to new arguments against the proposed amendment.

Advocacy groups promoting religious liberty have appeared in rising numbers, with big budgets and strong legal talent, and are moving on a variety of fronts to try to keep government from intruding into or shaping the moral debates and culture wars in society. Now, there are at least four Justices on the current Supreme Court who have shown strong sympathies for the threats they perceive to religious liberty.

On the other side of cultural conflict over sex equality, the “me-too” movement has newly energized women’s rights activists, as was so vividly on display in the huge march on Washington the day after President Trump’s inauguration in 2017. The new push for “just one more state” to ratify may well have borrowed some of that energy.

The idea of ERA, from its very origins in the early 1920s, drawing initial strength from the ratification of the 19th Amendment and its guarantee of equal voting rights for women and later gaining added strength from a widening women’s rights movement, has always been in the midst of or near to America’s cultural war zones.

In 2019, it can be assumed, the last chapter on the ERA has not yet been written. If one more state joins the cause, another chapter will open.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.