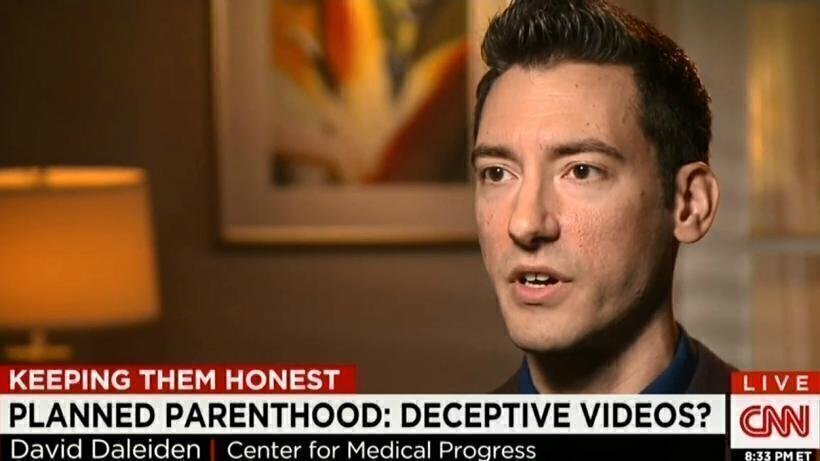

Last year, the Center for Medical Progress released a number of videos that appeared to show Planned Parenthood officials discussing the illegal sale of fetal tissue. Planned Parenthood, a national reproductive health services provider that also offers abortion services, flatly rejected the allegations made by the Center, and asserted that the videos were doctored to misrepresent what had taken place.

Last year, the Center for Medical Progress released a number of videos that appeared to show Planned Parenthood officials discussing the illegal sale of fetal tissue. Planned Parenthood, a national reproductive health services provider that also offers abortion services, flatly rejected the allegations made by the Center, and asserted that the videos were doctored to misrepresent what had taken place.

As the dispute garnered national attention, multiple investigations across several states were initiated. Then, in late January, a grand jury in Texas announced two surprising indictments. No wrongdoing was found on the part of Planned Parenthood, but the jury indicted two officials from the Center for Medical Progress on charges of tampering with a governmental record and attempting to purchase human organs.

In response to these charges, officials from the Center released a statement defending its members, which in part said that the organization “uses the same undercover techniques that investigative journalists have used for decades in exercising our First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and of the press, and follows all applicable laws.”

While this case stirs more public debate about abortion and the role of government in funding of healthcare providers like Planned Parenthood, it also raises questions about the extent of First Amendment protections for journalists who go to great lengths to get a big story.

Speaking to WNYC’s On the Media, Jane Kirtley, professor of media ethics and law at the University of Minnesota, explained that it is not clear that the First Amendment allows journalists to engage in illicit activities in the process of their reporting. The Supreme Court has only affirmed the right of newspapers and other media outlets to publish documents that were given to them by a third party who obtained them illegally.

In New York Times v. United States (1971), for example, the Court held that the First Amendment protected the newspaper’s right to publish the Pentagon Papers, writing that, if a newspaper “lawfully obtains truthful information about a matter of public significance … then state officials may not constitutionally punish publication of the information, absent a need … of the highest order.”

But the Court did not extend that protection to the individual who broke the law to initially obtain that information. In fact, Daniel Ellsberg, who leaked the Pentagon Papers to the New York Times after illegally obtaining them, was charged with six counts of espionage, six for theft, and one for conspiracy. Although his prosecution ultimately ended in a mistrial due to government misconduct, it was clear that the Supreme Court did not understand the First Amendment to excuse illegal activity, even it furthered some journalistic interest or end.

More recently, the Court ruled in Bartnicki v. Vopper (2001) that the publication of illegally obtained content was protected by the First Amendment, but again did not grant the same protection from prosecution to the individuals who obtained the content.

The application of this principle was also in the national spotlight in 2013, when the former NSA contractor Edward Snowden was charged with two crimes under the Espionage Act for copying classified information. No similar charges were filed against The Guardian, which first published his revelations.

But what if the journalists themselves carry out the illegal activity? In 1999, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit faced a case invoking this very question.

The case originated when ABC reporters applied for jobs at the Food Lion grocery chain after they received tips indicating food safety violations in Food Lion stores. After the story ran, the Food Lion sued ABC and its reporters for “fraud, breach of the duty of loyalty, trespass, and unfair trade practices,” and sought millions in compensatory and punitive damages.

The Fourth Circuit determined that the ABC journalists did break the law as they chased this story, and wrote that even though the publication of the story was in the public interest, the press “has no special immunity from the application of general laws.” Generally applicable laws, like those against trespassing, do not run afoul of the First Amendment even if their “enforcement against the press has incidental effect on its ability to gather and report the news.”

Other attempts at recognition that the First Amendment grants special privileges to journalists have failed. In 1971, for example, the Supreme Court ruled that requiring reporters to disclose confidential information about sources to grand juries served a compelling state interest and passed First Amendment scrutiny.

Along with the Texas indictments, the Center for Medical Progress might be subject to other criminal prosecutions and liability payments to Planned Parenthood. In a complaint to a federal court in California, Planned Parenthood argues that Center officials violated federal laws while procuring their secret videos, and is seeking civil and punitive damages.

While the public can have a robust debate about the balance between the interests of law enforcement and investigative journalism, courts generally do not appear receptive to the argument put forth by the Center for Medical Progress. Even if it is later determined that Planned Parenthood indeed engaged in criminal wrongdoing, current First Amendment jurisprudence dictates that two wrongs don’t make a right.

Jonathan Stahl is an intern at the National Constitution Center. He is also a senior at the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in politics, philosophy and economics.