Ten years ago in a public conversation, journalist Marvin Kalb asked the late Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia what he would do if he could change the U.S. Constitution. Scalia replied that he would make the Constitution easier to change.

Scalia told Kalb that based on his calculations (which some have questioned), less than 2 percent of the population could prevent an amendment to the Constitution. “It ought to be hard, but not that hard,” Scalia said.

Scalia told Kalb that based on his calculations (which some have questioned), less than 2 percent of the population could prevent an amendment to the Constitution. “It ought to be hard, but not that hard,” Scalia said.

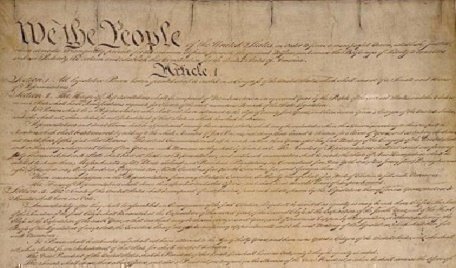

Perhaps in drafting Article V, which sets out the primary paths for amending the Constitution, the Framers intended the process to be difficult but had no idea how difficult it would be when their young nation grew to 50 states and more than 300 million people. What is certain, as the “Great Chief Justice” John Marshall once wrote, is that they wanted the Constitution to be an “enduring” document. They knew that for it to meet the challenges or crises of the future, the document would need amendments.

Article V states that an amendment must either be proposed by Congress with a two-thirds majority vote in both the House of Representatives and the Senate, or by a constitutional convention called for by two-thirds of state legislatures. A proposed amendment only becomes part of the Constitution when ratified by legislatures or conventions in three-fourths of the states (38 of 50 states).

The difficulty in reaching the finish line has not dissuaded proponents of amendments. Approximately 11,848 measures have been proposed to amend the Constitution from 1789 through Jan. 3, 2019, according to the most recent U.S. Senate’s records. The last ratified amendment was the 27th Amendment in 1992 (“No law varying the compensation for the services of the Senators and Representatives shall take effect, until an election of Representatives shall have intervened.”).

The late Justice John Paul Stevens even authored a book after he retired that detailed six amendments he believed should be approved and his reasons for them (“Six Amendments: How and Why We Should Change the Constitution”).

Still, only 27 amendments have been ratified out of 33 passed by Congress and sent to the states. And convention calls have fared even worse despite hundreds of calls by state legislatures on a variety of subjects. The latter failure was just fine with Scalia who also told Kalb, “I certainly would not want a constitutional convention. Whoa! Who knows what would come out of it?”

All of this, plus the close political divide in Congress, are why Republican House Speaker Mike Johnson could say confidently that President Joe Biden’s recent Supreme Court reform proposals—two of which would require constitutional amendments—were “dead on arrival” in the House.

Biden’s proposed amendments first would overturn the Supreme Court’s June decision holding that presidents and former presidents are largely immune from criminal prosecution for official acts during their time in office, and second, would impose 18-year term limits on justices.

Justice Stevens’ six amendment proposals would have overruled 5-4 decisions by the Supreme Court. But success in overturning Supreme Court constitutional decisions also has been rare. In his 2014 review of the justice’s book, law professor Geoffrey Stone noted that of the 27 amendments that did cross the finish line, only two overrode an interpretation of the Constitution by the Supreme Court.

Those two were: the 11th Amendment, adopted in 1798, overriding the decision in Chisolm v. Georgia (1793), which had held that a citizen of South Carolina could sue the State of Georgia, and the 16th Amendment, adopted in 1913, overriding the decision in Pollock v. Farmers Loan and Trust Co. (1895), which had held unconstitutional the federal income tax. The bottom line, Stone wrote: “On average, then, the nation has amended the Constitution in order to override Supreme Court interpretations of the Constitution roughly once every 112 years.”

The Biden proposals don’t seem to have much of a future based on history alone. But times do change. The coming election could change the landscape for proposed amendments. The immunity Supreme Court decision is quite unpopular, and there appears to be increasing support for Supreme Court term limits.

And perhaps someday there will even be an amendment to make changing the Constitution “hard, but not that hard.”

Marcia Coyle is a regular contributor to Constitution Daily and PBS NewsHour. She was the Chief Washington Correspondent for The National Law Journal, covering the Supreme Court for more than 30 years.