On Tuesday, President Barack Obama jested that he could win a third term in office, but that he was also glad he was constitutionally barred from running. While Obama spoke in a context about African leaders, the comments caused discussion back home about third-term Presidents in general.

In his speech in Ethiopia, President Obama was cheered when he said he couldn’t run for office and cheered again when he said he believed he could win a third term. The crowd then cheered when Obama said he was glad he couldn’t run.

In his speech in Ethiopia, President Obama was cheered when he said he couldn’t run for office and cheered again when he said he believed he could win a third term. The crowd then cheered when Obama said he was glad he couldn’t run.

Link: Video Of The Speech

“I love my work. But under our constitution I cannot run again,” Obama said to loud applause. “I actually think I'm a pretty good president. I think if I ran I could win. But I can't,” he said as the audience laughed and cheered.

“People like George Washington forged a lasting legacy not only because of what they did in office, but because they were willing to leave office and transfer power peacefully,” Obama said, as he implored African leaders to respect term limits in their constitutions. “Nobody should be president for life,” he added.

The Washington Post’s Philip Bump picked up on the comments and did a hypothetical story of Obama’s odds of getting the Democratic nomination and a general election win if he could run – in an alternative universe.

“Had there never been a Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and therefore no 22nd Amendment to the Constitution, the 2016 election cycle might look very different,” Bump wrote.

While Bump didn’t make any predictions about a fictional 2016 presidential race, he said that Obama would be in “pretty good shape” to be the Democratic nominee if popularity ratings were an indicator.

But he also pointed to another key indicator – a November 2014 Economist/You Gov poll that showed 19 percent of all Americans, and just 39 percent of Democrats, wanted Obama to run again if the 22nd Amendment didn’t exist.

For generations, Americans and politicians veered away from the concept of a third-term President. Washington had set an unofficial precedent in 1796 when he decided several months before the election not to seek a third term.

In 1799, a friend again urged Washington to come out of retirement to run for a third term. Washington made his thoughts quite clear, especially when it came to new phenomena of political parties.

“The line between Parties,” Washington said, had become “so clearly drawn” that politicians “regard neither truth nor decency; attacking every character, without respect to persons – Public or Private, – who happen to differ from themselves in Politics.”

Washington’s voluntary decision to decline a third term was also seen as a safeguard against the type of tyrannical power yielded by the British crown during the Colonial era.

Between 1796 and 1940, four two-term Presidents sought a third term to varying degrees. Ulysses S. Grant wanted a third term in 1880, but he lost the Republican Party nomination to James Garfield on the 36th ballot. Grover Cleveland lacked party support for a third term but was a rumored candidate. Woodrow Wilson hoped a deadlocked 1920 convention would turn to him for a third term.

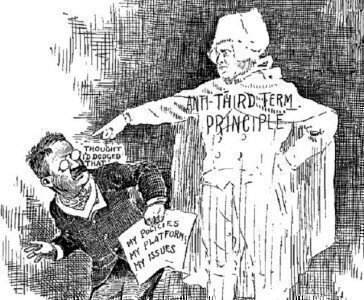

Even the popular Theodore Roosevelt couldn’t get by party objections to a third term. Roosevelt passed on running for a third consecutive term in 1908, fully aware of the Washington precedent. But after a fallout with President William Howard Taft, he sought a third nonconsecutive term in the 1912 presidential election. He lost the election but came in second ahead of Taft.

It was left to Franklin Roosevelt to break the third-term unwritten rule. In 1940, FDR decided to go against the George Washington precedent after World War II broke out in Europe and Nazi Germany overran France. The move caused some key Roosevelt supporters within the Democratic Party to leave his campaign. Roosevelt insisted that he was in the race to keep America out of war in Europe, and he easily defeated Wendell Willkie on Election Day.

After Franklin Roosevelt died in 1945, momentum built quickly for a presidential term-limits amendment. Congress passed it in 1947, and it was ratified by the states in 1951.

“No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice, and no person who has held the office of President, or acted as President, for more than two years of a term to which some other person was elected President shall be elected to the office of the President more than once,” the amendment read, in a clear reference to Roosevelt.

But even after the 22nd Amendment was ratified, two Presidents had aspirations of a third term within the amendment’s limitations. Harry Truman was President when the amendment was proposed and ratified, and its language allowed for Truman to run for office in 1952. But a loss in the New Hampshire primary led to Truman’s withdrawal from the race.

And in 1968, President Lyndon Johnson was eligible to run since he assumed the presidency in late 1963. Johnson also dropped from the presidential race after a disappointing showing in New Hampshire amid poor poll numbers.

So among the two-term Presidents who had third-term hopes, just FDR is among the seven possible candidates who won re-election, and a constitutional amendment soon followed his 1944 election, to a fourth term, to prevent another full three-term scenario.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.