Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at how the Court’s Bank Markazi ruling may redefine how Congress can influence a court case. The wheels of justice sometimes turn slowly in the nation’s courts, but much of the time, the two sides must simply wait for the process to run its course toward a decision. In the federal courts, though, it may now be possible for a frustrated individual or organization with a lawsuit to turn to Congress with a plea for it to take sides in that specific case and decide – or at least strongly influence -- how it should come out.

The wheels of justice sometimes turn slowly in the nation’s courts, but much of the time, the two sides must simply wait for the process to run its course toward a decision. In the federal courts, though, it may now be possible for a frustrated individual or organization with a lawsuit to turn to Congress with a plea for it to take sides in that specific case and decide – or at least strongly influence -- how it should come out.

That is one of the potential results of a major Supreme Court decision on Wednesday, testing the constitutional doctrine of the separation of powers among the branches of the national government. The decision came in a case involving the congressionally imposed duty for the government of Iran to pay off hundreds of victims of Mideast terrorist acts that the Iranian regime has been found to have sponsored. Just how far that decision, in the case of Bank Markazi v. Peterson, goes beyond this particular controversy will depend upon how expansively courts interpret that ruling in future cases.

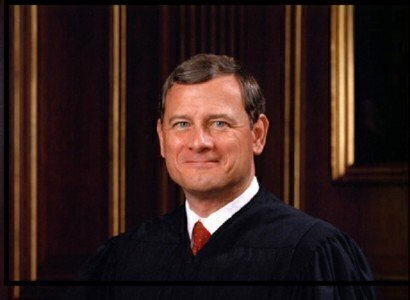

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., in a history-laden dissent, seemed to be cautioning lower courts to apply narrowly the principles of the ruling if anyone else succeeds in getting Congress to make a similar foray into shaping a pending court case.

Roberts warned that, as the majority had decided the case, it amounted to a significant shift of judicial power away from the courts and to Congress. The ruling, he said, could become “a blueprint for extensive expansion of the legislative power at the judiciary’s expense.” The Chief Justice recalled that the Founder, James Madison, had warned against “Congress’s tendency to extend the sphere of its activity and draw all power into its impetuous vortex.”

Whatever the future prospect is, that case could have produced a historical constitutional debate between Supreme Court Justices over how the Constitution does – or does not – insulate the federal courts created by Article III from efforts by Congress to shape how they decide specific pending cases. As the case turned out, however, only the dissenting Justices felt obliged to dig deeply into constitutional history to guide their analysis. The majority hardly answered that recitation of history as it upheld the federal law at issue, finding it to be a valid exercise of legislative authority hardly different in kind from other statutes that change existing law with the change then affecting ongoing court cases.

The Bank Markazi case was begun in a variety of lawsuits by some 1,300 individuals, victims (or their families) of terrorist bombings in Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. They had won billions of dollars’ worth of court rulings against the Iranian government, and had turned to the federal courts to try to collect. They discovered that the central bank of Iran, named Bank Markazi, had about $1.75 billion in assets in a New York City bank, so they went after that to satisfy at least part of what they were owed under the court judgments.

When that bogged down in the refusal of the Iranian government to recognize an obligation to pay, the lawyers for the victims turned to Congress in 2012. What emerged from their lobbying efforts was a law tailored very specifically to their case. Not only did it identify that case by specific citation of its court docket number; the 2012 law also specified that it was declaring the law only for that case, and could not be applied to any other case.

The law told the federal courts that, if they found that the assets in the New York bank did belong to Bank Markazi, and that no one else owned them, it would be obliged to award those assets to the victims and their survivors and families. Was that a legislative takeover of the court case, or was it merely a change within Congress’ power to alter existing law? That was the issue before the Supreme Court.

The decision emerged Wednesday, and the victims won, by a 6-to-2 vote.

From the perspective of the majority, speaking through an opinion by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the law was not, in fact, a law to govern just a single case but a stack of consolidated lawsuits filed by various combinations of the victims, and the law was little different from many laws that Congress passes that are narrow in scope and, sometimes, benefit only a single individual or organization and have an impact on existing court cases.

The Chief Justice, in a dissent joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, viewed the congressional initiative as an unprecedented intrusion into the business of the courts, targeting a specific case and leaving so little for the courts to decide to complete it that the law could only be understood as a mandated victory for the victims.

The very idea of an independent judiciary, created by the Constitution’s Article III, Roberts wrote, was to change away from a practice in the colonial governments of letting legislatures act like courts, with legal outcomes depending upon shifting political sentiments.

Roberts also relied heavily upon a Civil War-era precedent, the court’s 1872 ruling in United States v. Klein, which he said was the first ruling by the court to enforce the judicial independence that has been assured by Article III. That ruling, he said, affirmed “the bedrock rule of Article III that the judicial power is vested in the Judicial Branch alone.”

By contrast, the Ginsburg opinion for the majority suggested that the 1872 precedent was only a puzzling ruling, that actually did not stand as a sturdy guarantor of judicial independence, but was little more than an attempt to advise Congress not to require courts to take steps that would violate the Constitution. Whether it was the majority’s intent to belittle that often-cited precedent, the apparent effect was to do just that.

It also is not clear why the majority opinion did as little as it did to counter the historical arguments mounted by the dissent. But by keeping the focus only on its interpretation of the specific law that Congress had passed in 2012 on access to the Iranian government assets for the terrorism victims, Justice Ginsburg and her supporting colleagues may simply have been implying that this case did not provide the occasion for a broad inquiry into constitutional history. Even so, it would have been fascinating – and useful -- to have had a rebuttal to the Chief Justice’s recitation.