An array of historical facts looms in the background of the revived movement to choose the American President by a different method. That history will come into new focus, it now appears, because abolishing the Electoral College is rapidly becoming a prominent issue in the already-begun presidential campaign of 2020.

Completely replacing that method could be done with a constitutional amendment, but history, as well as contemporary politics, may be stacked against that option.

Completely replacing that method could be done with a constitutional amendment, but history, as well as contemporary politics, may be stacked against that option.

It is a fact that the idea of reforming or replacing the Electoral College has been talked about in America since 1797, only eight years after the newly created U.S. government took office. But an amendment to change the College was last put in the Constitution in 1804, after the nation was nearly torn apart by the election of 1800 that eventually put Thomas Jefferson in the White House. (That was the 12th Amendment, requiring that the College electors vote for President and Vice President separately.)

A second cautionary note from history is that proposed amendments to reform or replace the Electoral College outnumber all other constitutional changes ever proposed, throughout the whole of American history, and yet not once since 1804 has any succeeded.

Turning from history to modern politics, the talk of doing away with the Electoral College always gets a temporary boost in popularity after a President is elected with a majority in the College, beating out a candidate who won more popular votes nationwide. That happened after George W. Bush’s victory in 2000, and it is happening now in the wake of Donald J. Trump’s victory in 2016.

Such a discussion gets muddled by suggestions of the illegitimacy of the outcome. The Supreme Court gets blamed for supposedly skewing the 2000 election, and any number of factors – including possible foreign government intervention – cloud the 2016 result.

With American political sentiments as deeply polarized as they now are, it seems more than doubtful that the two main parties could agree to summon a two-thirds vote of approval in each of the two houses of Congress and then a three-fourths vote in state legislatures to ratify an Electoral College amendment.

Moreover, there appears to be nothing close to a consensus among political analysts about which major political party would get the benefit from adopting the most widely suggested alternative: a direct vote of the people, with the candidate getting the most votes nationwide winning the presidency.

Democrats probably would harvest strong vote totals in the states on the coasts and some major cities while Republicans would probably do the same in the South and some parts of the Midwest and the mountain states. There is always a debate about how campaigns would be run if presidential candidates have to seek votes in all states, rather than concentrating on just a handful of so-called “battleground states.”

One of the fundamental grievances with the Electoral College is that states with small populations have exaggerated power in the College because every state, under the Constitution, is guaranteed two U.S. Senators, regardless of state population, and each Senate seat represents a vote in the College. However, there is no way to amend the Constitution to take away the equality of Senate seats among the states because the Constitution itself forbids a change of that provision for any state unless it consents – and that won’t ever occur.

But if a constitutional amendment to bring about a direct popular vote seems out of reach, could it be achieved some other way?

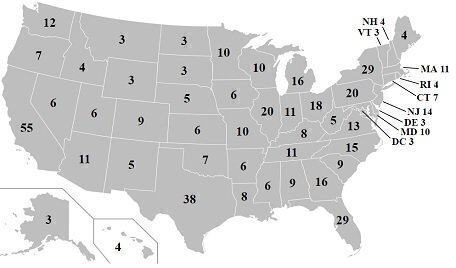

There appears to be gathering momentum for what is called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact – an idea that would not require a constitutional amendment although it would leave the Electoral College in place. The plan, which has now been embraced in 14 states and the city of Washington, D.C., would commit those states to cast all of their Electoral College votes for the presidential candidate who had won the most popular votes nationwide. The plan would go into effect only when enough states had signed on to add up to at least 270 votes (the minimum needed to win in the Electoral College). How each such state’s voters had cast their ballots would not displace the national winner as the recipient of that state’s electoral votes.

As of now, the signing states plus Washington, D.C., together have 70 percent of that minimum of 270. This movement began in 2006, but seems lately to be gaining new popularity, as three of the 14 states have just joined the list recently; those three states have 17 votes in the College, pushing the total of all the signing states to 189. Where the remaining signing states are to be found, though, is unclear at this point.

There is yet another possible way to keep the Electoral College but alter the way its votes are counted. That alternative is to turn to the courts, but – so far – three lawsuits have ended in three defeats in federal trial courts.

A key feature of the Electoral College as it has long existed is that most states, using the power the Constitution gives them to choose, have adopted laws that give all their electoral votes to the candidate who receives the most votes in each state. (Now, 48 states – all but Maine and Nebraska – plus Washington, D.C., use this winner-take-all approach; those two states award their votes according to who wins the most votes in congressional districts.)

The theory of the court challenges to the winner-take-all system is that it violates three provisions of the Constitution and a section of the federal Voting Rights Act.

A claim under the 14th Amendment is that winner-take-all unequally favors the winner of a bare plurality of the popular vote, giving that candidate all of the state’s electoral states – something like a “one-person, one-vote” theory. A claim under the First Amendment is that this approach burdens the voting rights of those who cast their ballot as a statement of who should be President. A claim under the Voting Rights Act is that winner-take-all is illegal because it allows white voters to control the outcome, thus impairing the rights of minority voters.

In February, a federal judge in San Antonio dismissed all of those challenges to the state of Texas’s winner-take-all system. The judge relied on what he called controlling precedents from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit (its rulings are binding in Texas), rejecting a challenge to Alabama’s winner-take-all approach, and from the U.S. Supreme Court, rejecting a challenge to that approach in Virginia. Similar defeats came earlier in federal trial courts in California and Massachusetts.

Now, all three of those cases have moved on to federal appeals courts, so the issues they raise remain live controversies. The issue could return to the Supreme Court; the Court’s prior ruling in the Virginia case, Williams v. Virginia State Board of Elections, in 1969, was what is called a summary decision – issued without full briefing and a hearing. Such a ruling is not as strong a precedent as a full-dress decision after briefing and argument.

Lyle Denniston has been writing about the Supreme Court since 1958. His work has appeared here since mid-2011.