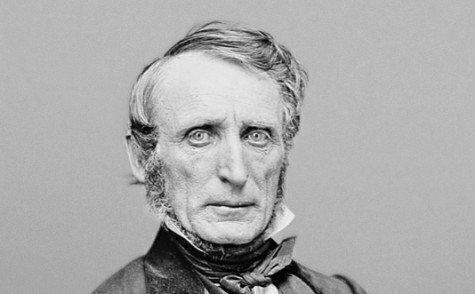

Although forgotten by most Americans, John Bingham is one of the most important figures in American constitutional history. Indeed, Justice Hugo Black called him the “Madison . . . of the Fourteenth Amendment.” And so he was.

Bingham’s professional credentials alone are astonishing. Prior to the Civil War, he was a leading antislavery voice in Congress. Following Lincoln’s assassination, he was a member of the team that prosecuted John Wilkes Booth’s co-conspirators. During Reconstruction, he was a leading Republican in the House and a key member of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. He also delivered the closing argument in President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial. And, following Bingham’s congressional career, President Ulysses S. Grant tapped him to be America’s minister to Japan, a position that he held for twelve years.

Bingham’s professional credentials alone are astonishing. Prior to the Civil War, he was a leading antislavery voice in Congress. Following Lincoln’s assassination, he was a member of the team that prosecuted John Wilkes Booth’s co-conspirators. During Reconstruction, he was a leading Republican in the House and a key member of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction. He also delivered the closing argument in President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial. And, following Bingham’s congressional career, President Ulysses S. Grant tapped him to be America’s minister to Japan, a position that he held for twelve years.

However, Bingham’s most lasting achievement was—appropriately enough for an entry in the National Constitution Center’s blog—constitutional. He was the main author of one of the most important pieces of text added to our Constitution after the Bill of Rights—Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Let’s begin with Bingham’s text:

No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

This language is so familiar that it’s easy enough to forget the constitutional revolution that Bingham and his fellow Second Founders wrought. For instance, we often forget that the 1787 Constitution was silent on the Declaration of Independence’s promise of equality. Not so today, and we have John Bingham to thank for that.

As ultimately ratified, the Equal Protection Clause uses sweeping, universal language, protecting all persons from discrimination. However, before settling on the universal text enshrined in our Constitution, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction had agreed on much narrower language, targeting the specific evil of racial discrimination. Since the proposed Fourteenth Amendment was drafted, in part, to address the evils of slavery and the future of the newly freed slaves, this move was fair enough. Nevertheless, Bingham convinced the Committee to scrap this agreed-upon language and broaden it.

Bingham’s new provision—the one that’s actually in the Constitution today—promised “equal protection of the laws” for all persons, not just African Americans. As Bingham explained, he sought “a simple, strong, plain declaration that equal laws and equal and exact justice shall hereafter be secured within every State of the Union,” guaranteeing “equal protection” for “any person, no matter whence he comes, or how poor, how weak, how simple—no matter how friendless.” Through the Equal Protection Clause, Bingham achieved just that.

In addition, we often forget that the 1787 Constitution didn’t protect Americans from state abuses of key Bill of Rights protections like free speech. And, indeed, many Southern states did violate core free speech rights throughout the antebellum period, banning abolitionist speech, with at least one state punishing such advocacy with death. In short, before Bingham, the Bill of Rights applied only to the federal government. Not so today, and, again, we have John Bingham and Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment to thank for that.

In the debates over the Fourteenth Amendment, Bingham stated this purpose directly, “The proposition pending before the House is simply a proposition to arm the Congress . . . with the power to enforce the bill of rights as it stands in the Constitution today.” He also explained, focusing on the specific evils he sought to eradicate, “Hereafter the American people cannot have peace, if, as in the past, States are permitted to take away the freedom of speech, and to condemn men, as felons, to the penitentiary for teaching their fellow men that there is a hereafter, and a reward for those who learn to do well.”

In the end, Bingham’s language was meant to provide new protections that would address the abuses of the former rebels and set important constitutional baselines for generation to come. In short, Bingham envisioned a federal Constitution that would protect the fundamental freedoms and equality of all Americans—a vision that “We the People” ratified when we added the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1868.

Over time, the impact of Bingham’s language has been monumental. Professor Gerard Magliocca explains this well in his recent (must-read) biography of Bingham: Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment “is the language that the Supreme Court used to desegregate the public schools, end discrimination against women, establish equal voting rights, and find the right to sexual privacy. [It] is also the text that extends most of the Bill of Rights to the actions of state governments.” And, of course, there are countless other blockbuster Fourteenth Amendment rulings—really, “John Bingham” rulings—that span the ideological spectrum, from the guarantee of marriage equality nationwide in Obergefell v. Hodges to the protection of individual gun rights in McDonald v. City of Chicago. It’s little wonder that the Fourteenth Amendment is a key part of a period that many scholars rightly describe as our Nation’s “Second Founding.”

Sadly, despite his constitutional achievements, John Bingham is largely forgotten today. That’s, in part, why my organization (Constitutional Accountability Center) is partnering with the National Constitution Center to organize a multi-year celebration of the 150th anniversaries of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments—our Nation’s Second Founding. This cross-ideological initiative is committed to bringing together scholars, thought leaders, and citizens from diverse philosophical and legal perspectives to commemorate and debate the meaning of the Second Founding, the original understanding of the Second Founding Amendments, and their contemporary significance. A key goal of this celebration is to introduce the American people to some of constitutional history’s forgotten heroes—heroes like John Bingham.

Professor Akhil Amar once observed, “Many of us are guilty of a kind of curiously selective ancestor worship—one that gives too much credit to James Madison and not enough to John Bingham.” Even as Madison is often labeled the “Father of the Constitution” and recognized as the primary author of the Bill of Rights, most Americans ignore the Second Founder who most worked to realize the universal promise of Madison’s Bill and Jefferson’s Declaration. With the Fourteenth Amendment set to turn 150, the time has come to change that.

Tom Donnelly is a Senior Fellow For Constitutional Studies at the National Constitution Center. When this article was first published in January 2016, Donnelly was counsel at Constitutional Accountability Center. For additional information on Bingham and his constitutional achievements, please see:

Gerard N. Magliocca, American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Akhil Reed Amar, The Bill of Rights: Creation and Reconstruction.

Michael Kent Curtis, No State Shall Abridge: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights.

Richard L. Aynes, The Continuing Importance of Congressman John A. Bingham and the Fourteenth Amendment, 36 Akron L. Rev. 589 (2003).

Richard L. Aynes, On Misreading John Bingham and the Fourteenth Amendment, 103 Yale L.J. 57 (1993).

Michael Kent Curtis, John A. Bingham and the Story of American Liberty: The Lost Cause Meets the “Lost Clause,” 36 Akron L. Rev. 617 (2003).