Phillis Wheatley was the first globally recognized African American female poet. She came to prominence during the American Revolutionary period and is understood today for her fervent commitment to abolitionism, as her international fame brought her into correspondence with leading abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic. Although often forgotten today, her poetry won the admiration of George Washington and Benjamin Franklin.

Wheatley was not the only notable African American period of the Revolutionary Period or the first. Jupiter Hammon was the first African American published in America in 1761 at the age of 50 and like Wheatley, he was a devout Christian who used the Bible and the language of liberty to criticize the institution of slavery. In 1778, Hammon wrote a poem for Wheatley, “An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, Ethiopian Poetess,” in which he presented Wheatley as arriving in America by divine providence.

Wheatley was not the only notable African American period of the Revolutionary Period or the first. Jupiter Hammon was the first African American published in America in 1761 at the age of 50 and like Wheatley, he was a devout Christian who used the Bible and the language of liberty to criticize the institution of slavery. In 1778, Hammon wrote a poem for Wheatley, “An Address to Miss Phillis Wheatley, Ethiopian Poetess,” in which he presented Wheatley as arriving in America by divine providence.

Wheatley was born in 1753 in Gambia. Around the age of seven or eight, she was forcibly kidnapped and brought across the Atlantic on the Phillis and was soon sold as a slave to John and Susanna Wheatley of Boston.

Wheatley’s intelligence was so apparent that the Wheatley family taught her to read and write while encouraging her to write poetry. As John Wheatley recalled later, Phillis quickly mastered the English language “to such a degree as to read any, the most difficult parts of the Sacred Writings, to the great astonishment of all who heard her.” By 1767, the 14-year-old Phillis had already published her first poem “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin.”

International fame came in 1770 with Wheatley’s elegy of the revivalist Baptist preacher George Whitefield. Whitefield was known for leading the “First Great Awakening,” the religious revival of the 1730s and 1740s which made salvation personal by focusing on emotional conversion and encouraging individual Bible reading.

In the elegy, the pious Wheatley discussed Whitefield’s care and concern for African-American slaves:

“Take him my dear Americans, he said/ Be your complaints on his kind bosom laid: Take him, ye Africans, he longs for you/ Impartial Saviour is his title due: Wash’d in the fountain of redeeming blood/You shall be sons, and kings, and priests to God.”

Americans and Europeans were impressed by both the power of Wheatley’s poetry and the inspiration of her personal biography. Yet, Wheatley’s success also brought skepticism among colonial printers who doubted whether a precocious enslaved woman could produce such vibrant poetry.

On October 8, 1772, a panel of 18 of the “most respectable characters in Boston” were assembled to verify the authorship of Wheatley’s poems—the majority of whom were slaveowners and included prominent independence leaders, religious scholars, poets, and infamous colonial governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchison. The panel was assembled by John Wheatley himself after Phillis Wheatley struggled to get a printer to publish her manuscript. No record was kept of the deliberations. Ultimately, the panel signed a letter publicly testifying to Wheatley’s authorship.

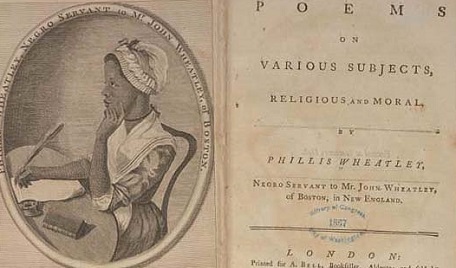

With the panel’s recognition of her authorship, Wheatley travelled to London in 1773 and with the help of Susan Wheatley’s English friends, she published her collected works of poetry, “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.” The Attestation of the panel was included in the preface and in advertisements as proof of authorship.

In one poem in the collection, she directly attacked slavery, asking:

“Wonder from whence my love of Freedom sprung; Whence flow these wishes for the common good/By feeling hearts alone best understood/I, young in life, by seeming cruel fate/ Was snatch’d from Afric’s fancy’d happy seat. . . Such, such my case. And can I then but pray/ Others may never feel tyrannic sway?”

Wheatley returned to America with the promise of Nathaniel Wheatley that he would grant her freedom, which he did one month after she returned.

In 1774, Phillis Wheatley continued to increase her public presence as an anti-slavery voice. Wheatley corresponded with key abolitionist figures: Reverend Samuel Hopkins, a theologian and leader of the emerging American abolitionist movement; British abolitionist leader Granville Sharp; and British merchant and philanthropist John Thorton, the sponsor of abolitionist preacher John Newton.

That year, in a published letter to her acquaintance Mohegan Indian Presbyterian minister Samson Occom, Wheatley wrote that:

“In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; It is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance; and by the Leave of our Modern Egyptians I will assert, that the same Principle lives in us.”

As Vincent Caretta writes, by “Modern Egyptian,” Wheatley meant to equate slave owners with the Pharaohs, the Old Testament villains, while presenting people of African descent as God’s chosen people to be saved by liberty and freedom.

During the Revolutionary War, Wheatley composed a poem for George Washington in which she wrote:

One century scarce perform’d its destined round/ When Gallic powers Columbia’s fury found; And so may you, whoever dares disgrace/ The land of freedom’s heaven-defended race!”

Wheatley composed the poem with hopes that Washington would apply the Revolution’s principles of equality and liberty to enslaved persons.

Washington wrote back on February 28, 1776, writing that he thought the “elegant Lines” of Wheatley’s poem were “striking proof of your poetical Talents." Washington suggested he would have published “this new instance of your genius” himself and invited Wheatley to visit his headquarters.

Wheatley’s work slowed down thereafter. She shared one of her last great poems on the Revolution in 1778, “On the Death of General Wooster,” in which she directly addressed the conflict between the Revolutionary ideals of freedom and the evils of slavery:

“With thine own hand conduct them and defend/ And bring the dreadful contest to an end/ Forever grateful let them live to thee/ And keep them ever Virtuous, brave, and free/ But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find/ Divine acceptance with th' Almighty mind/ While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace/ And hold in bondage Africa’s blameless race; Let virtue reign – And those accord our prayers/ Be victory our’s and generous freedom theirs.”

In 1778, Wheatley married John Peters, a free black lawyer and grocer. The now-Phillis Peters proposed to publish a second collection of poems in 1779. Wheatley failed to get enough subscribers despite putting out six advertisements for her new collection, ending her attempt to publish a second collection.

Between 1776 and 1784, she published just four poems and died in December 1784 at just 31. Yet, in her tragically shortened life, Wheatley’s poetry left an impression on both sides of the Atlantic as a global poet of the American Revolution and one of the first prominent African-American abolitionist voices.

Nicholas Mosvick is a Senior Fellow for Constitutional Content at the National Constitution Center.

Further Resources:

Vincent Carreta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (2011)

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers (2003)

Elizabeth Winkler, “How Phillis Wheatley Was Recovered Through History,” New Yorker, July 30, 2020, https://www.newyorker.com/books/under-review/how-phillis-wheatley-was-recovered-through-history