President-elect Donald Trump's recent comments about prosecuting flag-burning protesters has started yet another debate about the issue. But in the end, the only Justice left on the Supreme Court from the 1980s could have the final say on the matter.

Since Election Night, there has been a renewed interest in the constitutional subject after several anti-Trump protesters burned flags in public to protest his win over Hillary Clinton. On Tuesday, Trump added fuel to the debate with a provoking message on Twitter: “Nobody should be allowed to burn the American flag - if they do, there must be consequences - perhaps loss of citizenship or year in jail!”

Flag burning, as we’ve discussed in detail on this blog and at the National Constitution, is a legal debate that goes back decades, and in the minds of the Supreme Court, has been settled since 1990.

Special Podcast: Should we abolish the Electoral College?

In our Interactive Constitution project, scholars Geoffrey R. Stone and Eugene Volokh explained back in September 2015 the basic concept of symbolic speech in the First Amendment, which reads that Congress can’t make laws that “abridging the freedom of speech or of the press.”

“The Supreme Court has interpreted ‘speech’ and ‘press’ broadly as covering not only talking, writing, and printing, but also broadcasting, using the Internet, and other forms of expression. The freedom of speech also applies to symbolic expression, such as displaying flags, burning flags, wearing armbands, burning crosses, and the like,” said Stone and Volokh.

“The Supreme Court has held that restrictions on speech because of its content—that is, when the government targets the speaker’s message—generally violate the First Amendment. Laws that prohibit people from criticizing a war, opposing abortion, or advocating high taxes are examples of unconstitutional content-based restrictions. Such laws are thought to be especially problematic because they distort public debate and contradict a basic principle of self-governance: that the government cannot be trusted to decide what ideas or information ‘the people’ should be allowed to hear.”

Stone and Volokh also noted that hasn’t always been the case. “Courts have not always been this protective of free expression. In the nineteenth century, for example, courts allowed punishment of blasphemy, and during and shortly after World War I the Supreme Court held that speech tending to promote crime—such as speech condemning the military draft or praising anarchism—could be punished.” But since the 1920s, “the Supreme Court began to read the First Amendment more broadly, and this trend accelerated in the 1960s,” they concluded.

Two landmark Supreme Court decisions ruled on the burning of American flags at protests. In 1989, the Court first established flag burning as a protected First Amendment act in Texas v. Johnson. Back in 1984, Gregory Lee Johnson burned a flag at the Republican National Convention in Dallas in a protest about presidential candidates Ronald Reagan and Walter Mondale. Officials there arrested Johnson and convicted him of breaking a state law; he was sentenced to one year in prison and ordered to pay a $2,000 fine.

In June 1989, a deeply divided Court voted 5-4 in favor of Johnson, and against the state of Texas. Johnson’s actions, the majority argued, were symbolic speech political in nature and could be expressed even if it upset those who disagreed with him.

The Court’s Johnson decision only applied to the law in the state of Texas. In response, Congress passed a national anti-flag burning law called the Flag Protection Act of 1989 sponsored by a House member from Texas. The final bill approved by the Senate in October 1989 made “it unlawful to maintain a U.S. flag on the floor or ground or to physically defile such flag.” The bill, however, asked for an expedited Supreme Court review to consider “constitutional issues arising under this Act.”

There were flag-burning protests the day the federal law went into effect in late October 1989. Arrests were made at protests in Seattle and Washington, D.C., but federal judges dismissed the charges based on the Johnson decision. Government lawyers appealed directly to the Supreme Court, and the same Justices who heard the Johnson case considered United States v. Eichman in May 1990 – with the same outcome.

In the majority were Justices William Brennan (who wrote both majority decisions), Anthony Kennedy, Thurgood Marshall, Harry Blackmun and Antonin Scalia. The dissenters were Chief Justice William Rehnquist, John Paul Stevens, Byron White and Sandra Day O’Connor.

The decisions remain controversial to the present day, and Congress in 2006 attempted to pass a joint resolution to propose an amendment to the Constitution to prohibit flag desecration, which failed by just one vote in the Senate.

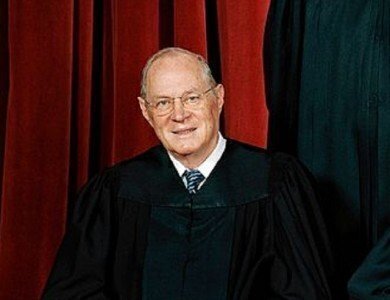

For the incoming President Trump, the only likely option short of a constitutional amendment would be a change of heart at the Supreme Court. But even with a new member joining the Court next year, there are four members of its liberal bloc still in place, as is Justice Anthony Kennedy, the only member of the 1989/1990 Rehnquist court on the current bench.

It was Kennedy who wrote the concurring opinion for the majority in the Johnson decision, where he agreed with the other four Justices (including Scalia) that Johnson’s “acts were speech, in both the technical and the fundamental meaning of the Constitution."

“The hard fact is that sometimes we must make decisions we do not like. We make them because they are right, right in the sense that the law and the Constitution, as we see them, compel the result,” Kennedy wrote in 1989.

“I do not believe the Constitution gives us the right to rule as the dissenting Members of the Court urge, however painful this judgment is to announce. Though symbols often are what we ourselves make of them, the flag is constant in expressing beliefs Americans share, beliefs in law and peace and that freedom which sustains the human spirit,” Kennedy added. “It is poignant but fundamental that the flag protects those who hold it in contempt.”

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.