On this day in 2010, the Supreme Court announced its ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission—a groundbreaking decision that continues to resonate in American politics and constitutional law.

The case began in 2008, amidst the heat of open presidential primaries on both sides of the aisle. On the Democratic side, U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton of New York was locked in a titanic struggle with her young counterpart from Illinois, Barack Obama.

The case began in 2008, amidst the heat of open presidential primaries on both sides of the aisle. On the Democratic side, U.S. Senator Hillary Clinton of New York was locked in a titanic struggle with her young counterpart from Illinois, Barack Obama.

Citizens United—then a relatively unknown conservative group—created a film entitled Hillary: The Movie, in which the aspiring presidential contender was presented in a critical and negative light. Clinton, the film said, was “steeped in sleaze.”

Upon seeking distribution through DirecTV and promotion through television commercials, however, Citizens United ran head first into the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, otherwise known as the McCain-Feingold Act. That 2002 law banned “electioneering communications” within 30 days of a primary election.

Citizens United challenged the regulation in court as a violation of the First Amendment. It lost at the district and circuit levels, but its appeal to the Supreme Court would prove more successful.

“No sufficient governmental interest justified limits on the political speech of non-profit or for-profit corporations,” wrote Justice Anthony Kennedy for a 5-4 majority. “For these reasons, political speech must prevail against laws that would suppress it, whether by design or inadvertence. … There is simply no support for the view that the First Amendment, as originally understood, would permit the suppression of political speech by media corporations.”

Chief Justice John Roberts agreed. “The First Amendment protects more than just the individual on a soapbox and the lonely pamphleteer,” he wrote in a concurrence.

Writing for the dissenters, Justice John Paul Stevens objected to the Court’s designation of corporations as persons under the First Amendment. “Corporations have no consciences, no beliefs, no feelings, no thoughts, no desires,” he wrote. “Corporations help structure and facilitate the activities of human beings, to be sure, and their ‘personhood’ often serves as a useful legal fiction. But they are not themselves members of ‘We the People’ by whom and for whom our Constitution was established.”

The ruling, he continued, “enhances the role of corporations and unions—and the narrow interests they represent—vis-à-vis the role of political parties—and the broad coalitions they represent—in determining who will hold public office.”

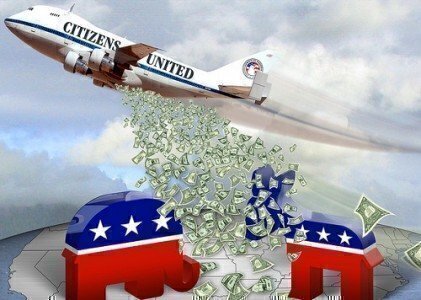

Since that day in 2010, much ink has been spilled over the ruling’s impact on American politics. Rightly or wrongly, “Citizens United” has become synonymous with the rising tide of money in political campaigns and a growing dissatisfaction with government. (It should be noted that Super PACs were not a direct outcome of the case.)

What is clear, though, is that the majority’s reasoning in Citizens United had an observable impact on later decisions. In McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission, the Court struck down limits on the total amount of money that can be donated to candidates or committees in one election cycle, drawing in part on free speech arguments in Citizens United.

And while the Supreme Court didn’t itself address the First Amendment in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby—a decision issued just two months after McCutcheon—lower courts cited Citizens United as support for corporate religious rights.

In the years ahead, the Court could very well revisit the famous case, probably with an eye to expanding its scope. The body politic may be done with Citizens United, but it’s not done with us.

Nicandro Iannacci is a web strategist at the National Constitution Center.