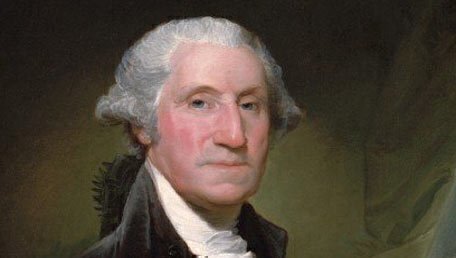

On September 19, 1796, a Philadelphia newspaper published one of the greatest documents in American history: George Washington’s Farewell Address.

Link: Read the entire Farewell Address

Link: Read the entire Farewell Address

Washington’s letter was significant in two ways: It signaled that Washington wasn’t running for a third term in office, and it served as a warning—and an inspiration—for future generations.

No less a critic than Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall said the address spoke to “precepts to which the American statesman can not too frequently recur.”

What makes the Farewell Address such a great speech? Here are five lessons we can learn from the first president about communicating.

1. Use great speechwriters

President Washington first considered a Farewell Address four years earlier, but the infighting between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson made Washington run for a second term, and he put the speech aside.

At the time, Washington asked James Madison to write a draft Farewell Address for his consideration. Then, in 1796, Washington asked his longtime aide, Hamilton, to do an extensive rewrite based on Washington’s concepts.

In the end, Washington stayed true to the points he felt were important, and he used elements of Madison and Hamilton’s work, too. But Washington wrote out the speech in his own handwriting, and he was its final editor.

The University of Virginia has an excellent online analysis of all the drafts.

2. Get right to the point

In the opening paragraph, Washington makes it clear by the end of the first sentence that he isn’t running for a third term of office. How often do you hear political speeches today where the major point is addressed immediately?

3. Make sure you thank everyone

In his second paragraph, Washington thanked the American people for the opportunity to serve—even though he was a near unanimous choice for president in two elections.

“I am influenced by no diminution of zeal for your future interest, no deficiency of grateful respect for your past kindness, but am supported by a full conviction that the step is compatible with both,” he says.

4. Unite your audience

After Washington thanked everyone and made sure they understood his decision was best for the country, he reminded the audience that they needed to remain united, despite their many differences. “The name of American, which belongs to you, in your national capacity must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations,” he says.

He also added a reminder about the then nine-year-old Constitution. “I shall carry it with me to my grave, as a strong incitement to unceasing vows that heaven may continue to you the choicest tokens of its beneficence; that your union and brotherly affection may be perpetual; that the free Constitution, which is the work of your hands, may be sacredly maintained; that its administration in every department may be stamped with wisdom and virtue,” he says.

5. Offer thoughtful advice

Most of the address is an extended policy statement about Washington’s eight years in office, as well some extended statements intended to make a point.

The two most famous statements in the Farewell Address are comments about political parties and foreign alliances. Washington didn’t like the idea of political parties (which he called “baneful”) and made that clear in a concluding statement in a passage about factions. “The common and continual mischiefs of the spirit of party are sufficient to make it the interest and duty of a wise people to discourage and restrain it,” he said.

The president also famously warned that the United States should stay “steer clear of permanent Alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Washington didn’t say that the young nation should be isolationist; in fact, he said that it should “observe good faith and justice towards all nations.”

But his advice was that any permanent alliance should be considered greatly. “I hold the maxim no less applicable to public than to private affairs, that honesty is always the best policy. I repeat it, therefore, let those engagements be observed in their genuine sense. But, in my opinion, it is unnecessary and would be unwise to extend them,” he added.

After the address was published in David C. Claypoole's American Daily Advertiser and then republished in countless newspapers and pamphlets, it appeared to be well received by the public However, it set off a frantic race to replace Washington between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson that helped to permanently create the political party system that Washington despised.

In later years, the Farewell Address letter gained new importance. In 1825, both Jefferson and Madison recommended the Farewell Address to the University of Virginia, as one of the best guides possible to the ideals of American government. During the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln recommended its public reading as a reminder.

And every year, a member of the U.S. Senate is asked to read the Farewell Address in public.

Scott Bomboy is the editor-in-chief of the National Constitution Center.