In recent days, another debate over American citizenship has surfaced in the presidential election that centers on the eligibility of a foreign-born candidate for office.

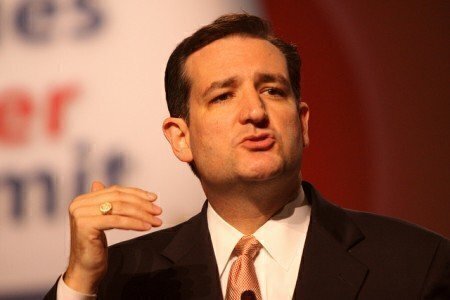

The most-recent controversy comes from GOP presidential candidate Donald Trump, who said on Sunday that rival Ted Cruz could face legal problems because Cruz was born in Canada to a father from Cuba and a mother who was a United States citizen.

“From Ted’s standpoint and from the party’s standpoint, he has to solve this problem, because the Democrats will sue him if he’s the nominee,” Trump said. “This matter has not been determined.” Cruz responded later that day on CNN. “The son of a U.S. citizen born abroad is a natural-born citizen,” Cruz replied.

Here is a basic explanation of how these citizenship concepts are related to the Constitution and to legal precedents.

The Constitution’s Natural Born Citizenship Clause states that “no person except a natural born Citizen, or a Citizen of the United States, at the time of the Adoption of this Constitution, shall be eligible to the Office of President.”

Sarah Helene Duggin from Catholic University, who is an expert on this topic, wrote at length for us about a potential Cruz candidacy back in October 2013, and she explained why many scholars believed Cruz was eligible.

Duggin said that the “consensus rests on firm foundations” based on the intent of the naturalization clause, as stated in a letter in 1787 from John Jay to George Washington; the language of the 1790 Naturalization Act; and the 14-year residency requirement in the Constitution’s Article II.

In the 1790 Naturalization Act, Duggin said the act provided that “children of citizens of the United States, that may be born beyond the sea, or out of the limits of the United States, shall be considered as natural-born citizens.”

But not everyone agrees with those arguments. Harvard’s Laurence Tribe, Cruz’s former professor, told the Guardian in a series of email exchanges that “there is no single, settled answer. And our Supreme Court has never addressed the issue.”

Tribe points out that two competing views of interpreting the Constitution could yield different results. The originalist view, he notes, might focus on concepts in place at the time of the Constitution’s ratification.

Tribe argues that an originalist might say “Cruz wouldn’t be eligible because the legal principles that prevailed in the 1780s and 90s required that someone be born on U.S. soil to be a ‘natural born’ citizen. … Even having two U.S. parents wouldn’t suffice for a genuine originalist. And having just an American mother, as Cruz did, would clearly have been insufficient at a time that made patrilineal descent decisive.”

Legislative attorney Jack Maskell, writing for the Congressional Research Service in 2011, explained how the gender of a parent was important historically in British common law, where the law of descent (known as jus sanguinis) indicated that "natural born" subjects were those born abroad of an English father.

Tribe also notes that a “living constitutionalist” judge who Cruz would dislike may find Cruz to “ironically be eligible because it no longer makes sense to be bound by so narrow and strict a definition.”

Cruz isn’t the first person to run for President born outside of the United States. In 2008, John McCain faced questions since he was born in the Panama Canal Zone. And Mitt Romney’s father, George Romney, was born in Mexico, and he faced questions during his 1968 presidential campaign.

Tribe also argues that the cases of Cruz and McCain are different. “[McCain’s] birth on a U.S. military base within a territory controlled by the US from 1903 to 1979 … under a treaty with Panama probably (although not certainly) qualified him as a natural born citizen, especially because both his parents were U.S. citizens at the time,” Tribe told the Guardian.

In his defense, Cruz has cited commentary from two legal authorities, Neal Katyal and Paul Clement, in a March 2015 Harvard Law Review article that said “there is no question that Senator Cruz has been a citizen from birth and is thus a ‘natural born Citizen’ within the meaning of the Constitution.”

“As Congress has recognized since the Founding, a person born abroad to a U.S. citizen parent is generally a U.S. citizen from birth with no need for naturalization. And the phrase 'natural born Citizen' in the Constitution encompasses all such citizens from birth,” Katyal and Clement argued. “Thus, an individual born to a U.S. citizen parent — whether in California or Canada or the Canal Zone — is a U.S. citizen from birth and is fully eligible to serve as President if the people so choose.”

Also, Maskell in his 2011 Congressional brief, found that “the weight of more recent federal cases, as well as the majority of scholarship on the subject, also indicates that the term ‘natural born citizen’ would most likely include, as well as native born citizens, those born abroad to U.S. citizen-parents, at least one of whom had previously resided in the United States, or those born abroad to one U.S. citizen parent who, prior to the birth, had met the requirements of federal law for physical presence in the country.”

To be sure, the debate over Natural Born Citizenship Clause will continue into the 2016 election cycle, and a definitive answer may not come until a lawsuit made its way to the Supreme Court (if the Court decided someone had standing to sue) or a constitutional amendment clarified the issue.