Senate Democrats opposed to several of Donald Trump’s cabinet-level nominees might be powerless to stop the nominations due to filibuster rule changes. But a closer look shows these moves were seldom used in past nomination fights.

The debate has begun in Washington, even among high-level Senate Republicans about Trump nominees Rex Tillerson and Jeff Sessions. But the rejection of either nominee as Secretary of State or Attorney General would be highly unusual given the Senate’s long-standing tradition of deferring to a President in selecting cabinet choices.

The debate has begun in Washington, even among high-level Senate Republicans about Trump nominees Rex Tillerson and Jeff Sessions. But the rejection of either nominee as Secretary of State or Attorney General would be highly unusual given the Senate’s long-standing tradition of deferring to a President in selecting cabinet choices.

And the filibuster, or lack of it, doesn’t seem to be a factor.

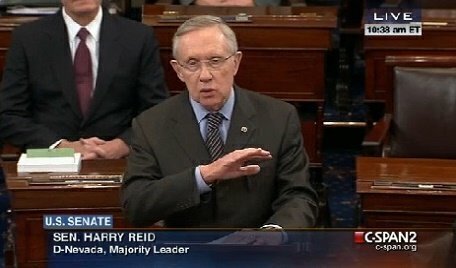

In November 2013, then Senate majority leader Harry Reid led the Democrats’ effort to kill the filibuster for cabinet-level and lower court nominees by making a rules change called the nuclear option. Prior to Reid’s move, a potential cabinet nominee needed 60 votes on the Senate floor to invoke cloture, a procedure that ended a filibuster and allowed a nomination to get a full vote on the Senate floor.

The Republicans in the Senate had used the filibuster to stall many of President Barack Obama’s judicial nominations. “The Founding Fathers never had any place in the Constitution about filibusters or extended debate,” Reid told reporters at the time. “This country operated fairly well for 140 years without filibuster protection.”

Republican Senate leader Mitch McConnell opposed the move and said it could hurt the Democrats in the future. “I say to my friends on the other side of the aisle, you’ll regret this. And you may regret it a lot sooner than you think,” he said in November 2013.

Next month, a new Senate will probably consist of 52 Republicans and 48 Democrats (and independents who caucus with the Democrats). Under the old math, Senate Republicans would need eight more votes to get to 60 votes to end a filibustered cabinet nomination. Now, they just need 51 votes.

That said, the use of filibuster and cloture procedures for cabinet nominations was rare even during the modern filibuster era, which began in 1967. According to a 2013 research report from the Congressional Research Service, cloture attempts were only made on seven occasions for cabinet-level nominees between 1967 and 2012.

Six of the nominees weren’t impeded by the cloture attempts and were easily confirmed: C. William Verity as Secretary of Commerce; Michael O. Leavitt as Administrator, Environmental Protection Agency; Stephen L. Johnson as Administrator, Environmental Protection Agency; Robert J. Portman as U.S. Trade Representative; Dirk Kempthorne as Secretary of the Interior; and Hilda Solis as Secretary of Labor.

Only John Bolton’s nomination as U.S. Representative to the United Nations was blocked by a failure cloture vote in 2005. President George W. Bush then appointed Bolton to the position using his recess appointment powers.

In general, Congress has been deferential to cabinet appointments made by a President for most of its history. According to Senate records, there have been more than 500 cabinet nominations considered by the Senate since 1789. Only nine cabinet nominations have been rejected by a Senate vote and another 13 nominations have been withdrawn.

The first high-profile cabinet rejection by the Senate was in 1834, when President Andrew Jackson lost a fight to get Attorney General Roger Taney named as treasury secretary, in the bitter fight over the Second Bank of the United States. The Senate rejected Taney’s nomination by a 18-28 vote, but a determined Jackson was able to get Taney appointed as the Supreme Court’s chief justice in 1835 when his Democratic

The last high-profile nomination rejection was in 1989 when the Senate, for the only time, voted down a former Senator as a cabinet member. President George H.W. Bush had nominated John Tower as defense secretary. Tower lost the vote along party lines in the Democrat-controlled Senate. Dick Cheney was later approved in Tower’s place.

Scott Bomboy is the editor in chief of the National Constitution Center.