Critics of presidential candidates Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton have accused each candidate of having the ability to create a constitutional crisis. Such claims, however, are nothing new. As constitutional scholars Jack Balkin and Sanford Levinson point out, the Constitution was written against a backdrop of perceived crisis, and so not surprisingly, the “language of crisis,” has been repeated throughout discussions of American politics and American constitutionalism since the Founding. Yet the label “constitutional crisis” has no fixed meaning.

People often label periods when government institutions are in conflict as “constitutional crises.” But Balkin and Levinson criticize the “promiscuous” use of the term “crisis” to describe constitutional conflicts of every size. The branches of American government are usually in conflict on a daily basis. Yet this is arguably the very purpose of the checks-and-balances system that the Framers envisioned, and rather than representing a constitutional “failure,” such conflict represents how the system is working properly. “If we were to say that every such confrontation was a crisis, we would have to conclude that the American Constitution was designed to place the country in a state of perpetual crisis,” they write

For instance, certain “constitutional crises”—like the “Saturday Night Massacre,” when President Nixon fired Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox—may be mere political crises. Many characterize President Roosevelt’s “Court-packing plan” of 1937 as a constitutional crisis, but Balkin and Levinson dispute this: “Roosevelt simply accepted his defeat and did not attempt to install extra Justices without congressional approval.” Even the impeachment of a president can hardly be seen as a constitutional crisis since procedures for impeachment are written into the Constitution.

So what constitutes a true “constitutional crisis”? Balkin and Levinson define a constitutional crisis as a major instance in history that serves “as a significant turning point in the existing constitutional order,” in which the order may have threatened to break down but instead may have resulted in an altered “status quo.” The secret, they note, is not to think of constitutional crises in terms of constitutional disagreement, but in terms of constitutional design. NCC scholar-in-residence Michael Gerhardt, in Crisis and Constitutionalism, describes constitutional crises similarly, as instances where there is no adequate constitutional mechanism available to solve a particular problem—when the Constitution “is of no avail.”

The clearest example of a true constitutional crisis was the Civil War. Arthur Bestor, in The American Civil War as Constitutional Crisis, explains how the Civil War actually encompassed a series of the most severe constitutional crises the country has faced. The War and events leading up to it also provide examples of three different types of constitutional crises that Balkin and Levinson define.

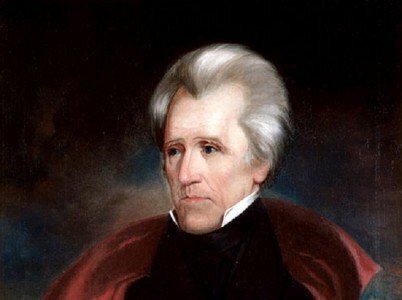

The first type of constitutional crisis results when “disagreements about the Constitution lead political actors to engage in extraordinary forms of protest”: people take to the streets, armies mobilize, and force is used or threatened. The Nullification Crisis under President Jackson was one such example. After Congress passed high protective tariffs on manufactured goods that favored the North, South Carolina declared the tariffs void in the Ordinance of Nullification, even threatening to leave the Union. President Jackson saw this move as treasonous and asked Congress for authorization to use military force against rebellious states. Congress passed both the Force Bill—which granted Jackson’s authorization—as well as a compromise tariff. In response to the compromise tariff, South Carolina rescinded the Ordinance. But the Crisis foreshadowed the eventual secession of the South. As Jackson wrote, “the tariff was only the pretext, and disunion and southern confederacy the real object. The next pretext will be the . . . slavery question.”

The next type of constitutional crisis is “when fidelity to constitutional forms leads to ruin or disaster.” This kind of crisis occurred when President Buchanan, Lincoln’s predecessor, sat by while the southern states seceded from the Union. Buchanan believed that the seceded states had violated the Constitution, but he also believed that “that the Constitution did not give the national government the power to prevent secession by using force”: Congress had the means to preserve the Union “by conciliation, but the sword was not placed in their hand to preserve it by force.” Yet following such formalism to its end would have destroyed the country and Constitution.

Conversely, President Lincoln recognized that the Constitution was intended to preserve a preexisting nation, and he believed that his constitutional duty to preserve the Union trumped all other obligations. But bending constitutional rules creates constitutional crises of a different sort. A third type of crisis thus emerges when political leaders believe that certain exigencies require violation of the Constitution. Some argue this happened when Lincoln unilaterally suspended the writ of habeas corpus, and ignored Chief Justice Taney’s ruling in Ex Parte Merryman that his suspension was unconstitutional by refusing to release the prisoner John Merryman. Others note that Lincoln believed that the Constitution granted the power to suspend the writ to both Congress and the executive, and Congress later sanctioned suspension anyway. But even if he had acted unconstitutionally, Lincoln thought it justified in order to preserve the Union; as he explained to Congress: “Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself to go to pieces, lest that one be violated?”

As Balkin summarizes, “if the goal of a constitution is to preserve political stability and make ordinary forms of democratic politics possible,” then “a constitutional crisis occurs when the constitutional system can no longer perform this function.” Such instances are rare episodes in which political leaders must recognize and address the inadequacy of the Constitution—which, by its nature as a determinate, written document, has limitations.

And how a president deals with a constitutional crisis can make or break both the country and his or her presidency. As Annette-Gordon Reed writes in her biography, Andrew Johnson, “Crisis widens presidential opportunities for bold and imaginative action. But it does not guarantee presidential greatness.” The inadequacies of Buchanan in the face of secession allowed Lincoln—who was more active and successful in meeting the challenge of crisis, and who is simultaneously ranked as one of our “best presidents”—to showcase “the difference that individuals make to history.”

Back to the 2016 election, and the portents of constitutional crisis: From Johnson to Nixon, Congress and the Supreme Court have been largely successful in checking executive power, as the legislative and judicial branches through checks-and-balances can step up to defend the Constitution. And of course, there’s always impeachment.

Therefore, while many commentators are concerned about whether the next president might create a constitutional crisis, they must also consider how well he or she might handle them.

Lana Ulrich is associate in-house counsel at the National Constitution Center.