Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at how comments from Justice Anthony Kennedy could lead to a stream of new cases from prisoners testing the constitutionality of solitary confinement.

THE STATEMENT AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENT AT ISSUE:

“Of course, prison officials must have discretion to decide that in some instances temporary, solitary confinement is a useful or necessary means to impose discipline and to protect prison employees and other inmates. But research still confirms what this court suggested over a century ago: years on end of near-total isolation exacts a terrible price….In a case that presented the issue, the judiciary may be required, within its proper jurisdiction and authority, to determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and, if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.

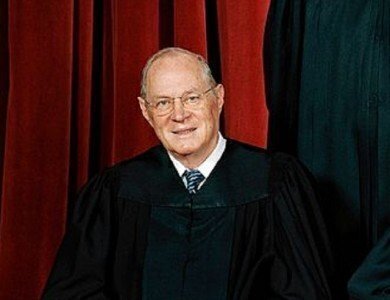

– Excerpts from an opinion by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, offering thoughts for himself in a criminal case the court decided on June 18, Davis v. Ayala. The case did not involve a challenge to solitary confinement, but Kennedy made his comments because he had learned from the case that the California death-row inmate, Hector Ayala, had been held in such segregation for most of his more than 25 years in prison.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

It is fact little known to many Americans, even if they have read or heard about Alexis de Tocqueville’s “Democracy in America,” that the French historian and political thinker did not come to America in 1831 to study its constitutional system or its political order: he actually came, in the first place, to study how Americans run their prisons.

He was especially fascinated by the then-new practice of operating prisons in more benign ways, with the aim not simply of punishing individuals for their crimes, but also attempting to rehabilitate them. The name “penitentiary,” in fact, was born of the Quaker idea, in establishing a Pennsylvania prison, that inmates should be given times of isolation to ponder how they had gone wrong, perhaps to become “penitent” and thereby become better human beings. That, at least, was one justification offered at the time for solitary confinement.

But as the 19th Century moved on, it became a reality, recognized both in America and in Europe, that solitary confinement was an especially debilitating and demeaning experience. As Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy noted (in the same opinion that is quoted above), “One hundred and twenty-five years ago, this court recognized that, even for prisoners sentenced to death, solitary confinement bears ‘a further terror and peculiar mark of infamy,’ ” quoting from the court’s 1890 decision in the case of In re Medley.

Kennedy also cited estimates that some 25,000 inmates in this country are currently serving their sentence “in whole or in substantial part in solitary confinement, regardless of their conduct in prison.”

It was that statistic, along with a host of other studies and commentaries mentioned by Kennedy, that had led him to suggest that the time had come for the courts to consider “the many issues solitary confinement presents.”

He did not spell out what those specific issues would be, but presumably he meant, among them, the question of whether it violates the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, or the Constitution’s guarantee of “due process,” to keep an inmate at least for years in the isolation of a small cell, with little human contact and almost no diverting activity.

One may expect, now that a member of the Supreme Court has highlighted the issue, and all but invited new test cases, that the courts will now begin to get a stream of new cases by prisoners testing the constitutionality of such confinement.

One case already working its way through lower courts is that of Albert Woodfox, who has spent more than 40 years in solitary confinement for his role in a murder of a prison guard in Louisiana in 1972. Recently, a federal judge in Baton Rouge barred a new trial of Woodfox for that crime, partly because of “the prejudice done to Mr. Woodfox by spending over forty years in solitary confinement.” That order has been temporarily put on hold while the state appeals, seeking a chance to try him for a third time after his two prior convictions have been overturned. But the point has been made: there may be a price to be paid, by prosecutors, in cases where lengthy solitary confinement has occurred.

If the estimates cited by Justice Kennedy are valid, there may be many such instances of prolonged stays in solitary, though perhaps that of Louisiana’s Woodfox may have set a record.

It does seem unlikely, though, that if such a test case does reach the Supreme Court, and gains review there, that the outcome will be a finding that solitary confinement, as such, is unconstitutional. The court has demonstrated repeatedly that it is prepared to leave to prison wardens and their staffs a very wide discretion to decide the details of prison management, including how to operate an internal disciplinary system.

But that tolerance, Kennedy has now suggested, may have constitutional limits. The court would have to depend upon experts in prison operation to aid it in crafting some standards for when prolonged segregation is too long, how to judge the validity of the initial decision to segregate a prisoner, how frequently should such confinement be reviewed to determine whether it continues to be necessary, and what kinds of alternative modes of punishment would meet the needs of the prison managers.

The court itself has no talent, and really no authority, to be a fact-finding institution itself on the question of prison reform, but it could surely expect – if it were to grant an inmate’s appeal on the issue – that experts and advocates in the field, on all sides, would come forth to file briefs to aid in the court’s inquiry.