Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at the Justice Department’s stance on Puerto Rico’s sovereignty, which will get tested twice in the Supreme Court this year.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“In a legal brief filed before the United States Supreme Court on December 23, 2015, the United States Government abruptly reversed course, and took the position that the Constitution and laws of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico do not emanate from the people of Puerto Rico after all. The brief takes the position that, under the United States Constitution, Congress has no power to authorize the people of a territory to engage in an exercise of popular sovereignty by democratically enacting their own Constitution, which then serves as the ultimate source of their laws. Under this view, there can be no such thing as meaningful self-government by the people of Puerto Rico under the U.S. Constitution.”

“In a legal brief filed before the United States Supreme Court on December 23, 2015, the United States Government abruptly reversed course, and took the position that the Constitution and laws of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico do not emanate from the people of Puerto Rico after all. The brief takes the position that, under the United States Constitution, Congress has no power to authorize the people of a territory to engage in an exercise of popular sovereignty by democratically enacting their own Constitution, which then serves as the ultimate source of their laws. Under this view, there can be no such thing as meaningful self-government by the people of Puerto Rico under the U.S. Constitution.”

– Excerpt from a letter sent December 26 by the governor of Puerto Rico, Alejandro J. Garcia-Padilla, to the United Nations Secretary General, reporting legal developments in Washington over the constitutional status of Puerto Rico – an issue that is before the Justices in two cases during the current term of the court. The letter could lead to a legal duty for the U.S. government to defend its current view of that status to the international body, as well as before the Supreme Court. (Read Full Letter Here.)

“The General Assembly recognizes that, when choosing their constitutional and international status, the people of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico have effectively exercised their right to self-determination….In the framework of their Constitution and of the compact agreed upon with the United States of America, the people of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico have been invested with attributes of political sovereignty which clearly identify the status of self-government attained by the Puerto Rican people as that of an autonomous political entity.”

– Partial text of the UN General Assembly Resolution 748, adopted on November 27, 1953, in response to notice by the United States government that it would no longer file required reports with the UN Secretary General under Article 73 of the UN Charter. That provision requires countries to keep the UN informed on conditions in territories which they hold that are not self-governing. The U.S government withdrew from that obligation by a memo dated April 20, 1953, saying that the adoption of a new constitution gave Puerto Rico “the full measure of self-government.”

“The United States did not characterize Puerto Rico as a sovereign. Instead, it noted that Puerto Rico had become self-governing while having no independent and separate existence from the United States.”

– Excerpt from a footnote in the federal government’s new legal brief filed last week in the Supreme Court opposing recognition of sovereignty for Puerto Rico, commenting on the position it had taken in the 1953 message to the UN.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

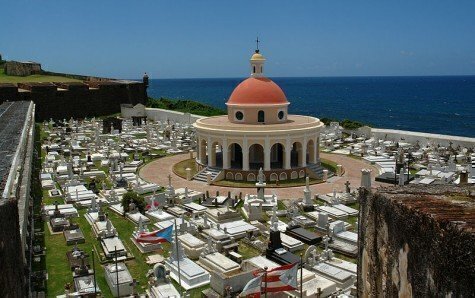

Puerto Rico has belonged to the United States since the American government won it as a prize of victory in the Spanish-American War in 1898. It has been a U.S. territory ever since, overseen and sometimes managed directly by Congress under the Territory Clause of Article IV of the Constitution.

Did that relationship change in 1950, when Congress gave the people of Puerto Rico the right to write and adopt their own constitution? Was that act of constituting a government of its own a sign that the islanders had acquired the genuine status of self-determination? Or did they remain in a dependent status, a little more self-governing than a traditional colony would have been, but something less than the sovereignty that U.S. states have always had?

Those are questions that have agitated the people of Puerto Rico in the six decades since their constitution went into effect in 1952, and it is clear that the islanders are not of one view about that, or about whether the time had come to seek statehood. The current government in power, however, is strongly in favor of establishing Puerto Rico as a sovereign entity, able to deal with the U.S. government with the same dignity and rank of a state even though it lacks actual statehood, but claiming that the 1952 constitution accomplished true autonomy.

Given how vital it is to have that constitutional question settled, it is remarkable that only now has it reached the Supreme Court and gained the Justices’ agreement to sort it out, at least in part. One case that the court will hear in January involved whether Puerto Rico prosecutors can charge individuals with the same crime for which they have already been convicted under charges filed in federal court. To be able, constitutionally, to stage its own independent prosecution for the same offense, Puerto Rico must be treated as a sovereign entity. Otherwise, the Double Jeopardy Clause prohibits sequential trials.

The other case, growing out of the island’s deepening crisis over its public debt, is asking the Justices to settle whether Puerto Rico can be treated less favorably than state governments when they seek to restructure their debt under federal bankruptcy law. (Congress debated doing something about the debt situation late in this year, but then decided to put off any action until March. By then, the Supreme Court will be fully engaged with the debt case pending there.)

Although each case at the court has a fairly narrow legal focus, both have led to a fundamental debate about just what constitutional status Puerto Rico is to have in 2016.

The Justice Department sent a real shock through the governing establishment of Puerto Rico last week when it inserted itself into the first case at the court, over criminal prosecution. Its brief made a blunt argument that the island is not now and never has enjoyed true sovereignty. Since then, the island’s governing leaders have been complaining publicly that this is not the position the federal government has had, and they are working energetically to prove that this is, indeed, a true switch that even negates what the government told the United Nations in mid-20th Century.

It is not clear what the United Nations might do in response to the governor’s letter, but his action has raised at least the prospect of some embarrassment for the U.S. government for seeming to have pulled Puerto Rico back into a semi-colonial status, just at a time when self-determination is again a global human rights issue.

The Supreme Court is probably in a better position, in a legal sense, to resolve the issue, but it is unclear how much it will feel free to second-guess the government’s official stance. It may look for a way to try to decide both cases narrowly, without resolving the sovereignty issue. But that might not be so easy, and the issue clearly is not going to go away.