Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at the Texas abortion case arguments, and the possibility of the case heading back to the lower-court system.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“The state, I think, is going to talk about the remaining clinics. Would it be (a) proper, and (b) helpful, for this Court to remand for further findings on clinic capacity?...Suppose there were evidence that there was a capacity and a capability to build these kinds of clinics [that would satisfy Texas law], would that be of importance?”

“Do you think the district court would have had discretion to say we’re going to stay this requirement for two-and-a-half, three years, to see if the capacity problem can be cured?”

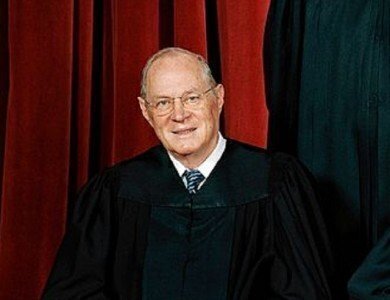

—Separate questions asked by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy during the Supreme Court’s hearing Wednesday on the constitutionality of a 2013 Texas law that imposed new restrictions on how abortion clinics were to be structured and operated. Kennedy appeared to be focusing mainly on what would happen to existing clinics in Texas if the court were to uphold those new restrictions, and, in particular, whether they could handle the demand for some 70,000 abortions a year in the state.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

In the Supreme Court’s rulings on abortion going back to Roe v. Wade 43 years ago, the Justices have never attempted to calculate how many abortion clinics were needed in a given state to serve women’s decisions to seek an end to their pregnancies. But they appear to have at least hinted that, if the number falls far short of the capacity needed to make sure that the right to an abortion remains secure in that state, that may result in a constitutional violation.

This is a kind of predictive numbers game that the court does not have the research staff to try to work out, but the Justices may be on the verge of launching such an inquiry in lower courts. The court was pondering that possibility on Wednesday, as it held its first significant abortion hearing in nine years. If it takes that step, suggested by Justice Anthony M. Kennedy (who appeared to be holding the key vote), the scope of abortion rights may not be clarified for a couple of more years. This constitutional right might thus be in a kind of limbo in the meantime.

The new case examined by the court, Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, does get into the question of the numbers of available clinics because one of the more recent tactics of state legislatures seeking to reduce the number of abortions in America has been to adopt strict clinic regulations that clinics contend they cannot afford to satisfy and still stay open. The legislatures have adopted such measures on the premise that they are necessary to protect women’s health, but the clinics and doctors have been challenging them on the premise that they are merely anti-abortion laws in a protective disguise.

In Texas, the legislature in 2013 adopted a requirement that any clinic performing abortions must upgrade its facilities to equal those of a surgical center. The clinics have argued that it could cost more than $2 million to upgrade in that way, and so the effect is to shut them down. The Texas law also includes a requirement that any doctor performing abortions must have the professional privilege of sending patients to a hospital within 30 miles of the clinic. That, too, was under review on Wednesday, but Justice Kennedy, in particular, seemed to be focusing mainly on the surgical requirement, as potentially the most demanding.

Several members of the court appeared to be troubled that the lower court proceedings in this case did not produce enough hard evidence of why clinics that have closed did so, and what the likely impact on others would be if the court were to uphold one or both of the 2013 restrictions.

This, for Kennedy, became a question of capacity should the number of clinics be significantly reduced because of the new law. In response to one of his questions about that, Kennedy was told by a federal government lawyer, U.S. Solicitor General Donald B. Verrilli, Jr. (on hand to support the clinics’ challenge), that the clinics that would be able to satisfy the law and thus stay open could only perform about 14,000 abortions a year, when the annual demand for abortions in Texas is somewhere around 70,000. “I really think this is the key,” Verrilli added, “because I do think this is the locus of the substantial obstacle [to Texas women’s abortion rights].”

Were the court to follow Kennedy’s suggestion that the data on prospective clinic closures be gathered with the case returning to lower courts, it would give this eight-member court (now without the late Justice Antonin Scalia) with a way to avoid splitting four-to-four on the constitutionality of the Texas law. The court does not like to divide evenly, especially on a major case, because that essentially accomplishes nothing. So, as the Justices begin discussing at a Friday morning closed-door conference what to do with the Texas case, the option of returning it for further development in lower court proceedings surely will come up.

It was more than obvious, throughout the hour-long hearing, that there are three Justices who very likely would vote to uphold the Texas law, and four who very likely would vote to strike it down. That, of course, would leave the controlling vote with the eighth Justice, Kennedy. He was the only one whose strong leanings were not clearly evident during the hearing, which ran for nearly a half-hour longer than had been scheduled.

The court will next meet in public next Monday morning, to announce action on pending cases. Although it may be too early for the Justices to have made up their minds about where to go with abortion law, it is not out of the question that there could be something to announce on Monday.

If the court is not able to compose a definitive ruling now on the Texas restrictions, the issue is surely likely to arise in cases from other states. Whether or not the court by then will have a full bench of nine Justices remains uncertain.