Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at the debate at the Supreme Court over qualifications placed on drugs used in lethal-injection executions.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“[Until the death penalty is ruled unconstitutional], is it appropriate for the judiciary to countenance what amounts to a guerilla war against the death penalty, which consists of efforts to make it impossible for the states to obtain drugs that could be used to carry out capital punishment with little, if any, pain? And so the states are reduced to using drugs which give rise to disputes about whether, in fact, every possibility of pain is eliminated.”

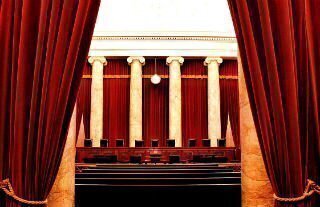

– Comment by Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., during a Supreme Court hearing on Wednesday on the constitutionality of the lethal-drug execution method that the state of Oklahoma now uses. The court is reviewing that issue in the case of Glossip v. Gross, involving three death-row inmates.

“The states have gone through two different [execution] drugs, and those drugs have been rendered unavailable by the abolitionist movement putting pressure on the companies that manufacture them so that the states cannot obtain those two other drugs….The reason this third drug is not 100 percent sure is because the abolitionists have rendered it impossible to get the 100 percent sure drugs, and you think we should not view that as relevant to the decision that you’re putting before us?”

– Comment by Justice Antonin Scalia, at the Glossip hearing Wednesday, to the lawyer for the three Oklahoma inmates.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

The Constitution is not a self-defining document, and every word of it needs interpretation and explanation from time to time. Since the 1879 decision in Wilkerson v. Utah, the Supreme Court has issued more than 40 major rulings interpreting the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment. Over the past few years, the controversy over the Eighth Amendment has focused closely on the use of lethal drugs to carry out death sentences.

Since a significant ruling seven years ago (Baze v. Rees), outlining some basic legal principles on the use of that method of execution, the Supreme Court has remained largely on the sidelines as several such executions went seriously awry, and states scrambled to find ways to avoid such spectacles and yet to continue to carry out executions of convicted murderers. A seriously complicating factor for the states was that the manufacturers of the drugs that supposedly worked most humanely in the process stopped making them available for executions.

Lawyers for death-row inmates have repeatedly asked the Supreme Court to give them a right to know just what procedures the states would use in execution chambers, so that they could test the constitutionality of those methods under the Eighth Amendment ban on “cruel and unusual punishment.” The court refused repeatedly even to consider those pleas, and refused regularly to stop executions even when inmates claimed that states had not adequately dealt with the problem of botched lethal-drug executions.

Because the Supreme Court almost never explains its refusal to take on an issue, even one of important constitutional dimensions, it has been a puzzle how the capital punishment regime could go on without a new examination by the Justices, especially in the wake of the flawed executions.

Now, quite suddenly, the Supreme Court has been drawn into the center of this ongoing Eighth Amendment controversy. It takes only four votes among the nine Justices to grant review of a case, and it seems likely that the four more liberal Justices, who have grown increasingly skeptical about lethal execution protocols, forced the issue before the court by voting to grant review of the appeal of three Oklahoma death-row inmates. (Those four Justices dissented earlier, when the court majority allowed one of the Oklahoma inmates to be put to death, even as the appeal by the four of them remained pending. That action, too, had gone unexplained.)

When that case (Glossip v. Gross) showed up on the court’s docket for review, it was unclear how broadly or narrowly the case might be decided once the court had agreed to take it on. What emerged most prominently, when the Justices held a one-hour hearing on that case on Wednesday, was the apparent frustration of the court’s most conservative members about the stalling of the capital punishment regime in the states – a stalling that those Justices suggested should be blamed upon the opponents of the death penalty.

Unable to get the Supreme Court or state legislatures to strike down or abolish capital punishment, the abolitionists, according to the conservative Justices, have tried to accomplish the same thing practically by making it next to impossible for states to adopt a workable and humane method of execution by lethal drugs.

Those complaints tended to dominate the hearing on the Oklahoma case on Wednesday, raising the prospect that at least some members of the court are looking for a way to insulate the states’ choices about execution methods, so that capital punishment again becomes practically available to them. Although the lawyer for the three Oklahoma inmates repeatedly reminded the court that what was before them was a question directly under the Eighth Amendment about whether the Oklahoma method did amount to “cruel and unusual punishment,” it appeared that some of the Justices were persuaded that it was a case about supervising how the lower courts react to the abolitionist movement’s tactics in frustrating states from carrying out executions.

Justice Alito, in particular, suggested that the judiciary, merely by hearing challenges to lethal-execution methods, were giving a forum to the abolitionists that they could continue to use to delay or block further executions. It would, of course, be an extreme measure, if the court were to move to shut down Eighth Amendment challenges in the lower courts. But, short of that, the court conceivably could require the lower appeals courts to avoid second-guessing what the trial court judges do when they turn aside challenges to execution methods.