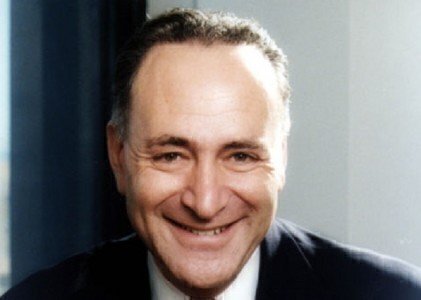

Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, looks at how Senator Chuck Shumer’s decision to oppose the Iran nuclear deal highlights our differences with the parliamentary system of government.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

“White House press secretary Josh Earnest…suggested lawmakers should question whether [New York Senator Charles] Shumer is fit to become the [Democratic] party’s leader in the Senate, saying members may want to ‘consider the voting record of those who want to lead the caucus.’ Close White House aides made similar arguments. ‘Senator Shumer siding with the GOP against Obama, [Hillary] Clinton and most Democrats will make it hard for him to lead the

Dems in ’16,’ Dan Pfeiffer, who served as Obama’s senior political adviser until leaving in February, wrote on Twitter. ‘The base won’t support a leader who thought Obamacare was a mistake and wants war with Iran,’ he wrote in another tweet.”

– Excerpt from a Washington Post story on August 8, reporting on the White House’s reaction to Senator Shumer’s announcement that he would vote against congressional approval of the new nuclear treaty between the U.S,, its allies and Iran.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

The generation of Founders who wrote the Constitution were not at all interested in imitating the English model of parliamentary government, with the powers to write the laws and to carry them out more or less united in one official body. Few ideas were more fundamental to the thinking of that generation than the need to separate the important powers a national government would exercise. Liberty itself depended upon such a separation, James Madison and others passionately believed.

In the American system that has evolved, the legislative program of the national government more often than not begins with what the president wants, and proceeds in Congress with the leaders aligned with the president’s political party working to enact it. Although the party leaders insist upon their independent authority, and the Constitution is supposed to guarantee that it exists, they are generally expected to act as the president’s legislative agents.

When – as is the case right now – the two houses of Congress have a majority in control whose leaders are from the other party, the president needs to count even more on his political allies on Capitol Hill; otherwise, he has to contend with two adversaries.

This relationship has to be a delicate balance, with the president respecting the need for his legislative allies to find their own ways to proceed (and sometimes the need not to proceed at all), given the political realities they face, and the allies respecting the need for the president to succeed at least with passage of the White House’s major policy initiatives.

By constitutional design, the president and members of Congress must answer to different political constituencies. That, too, is different from the situation with parliamentary government, where the governing party must first prevail in a nationwide election, and then chooses a prime minister to carry out the will of the electorate. Once a week, every Wednesday when Parliament is sitting, the prime minister must go before the House of Commons to defend the government’s ongoing program.

Because, in America, political accountability is very different, that can – and does -- complicate presidential-congressional relationships. This means that a president cannot casually assume legislative loyalty to the White House, and cannot make every piece of legislation a make-or-break test of that loyalty, and the White House’s allies in Congress cannot routinely pursue only their own agenda.

The obvious implication of this situation is that the White House must be very clear in choosing its most significant legislative priorities, and in calculating – in advance – how much it can give away in compromise if that should become necessary to achieving legislative success.

President Obama in coming weeks is facing a stern test of this very circumstance, as Congress debates whether to approve or disapprove of the proposed multi-nation deal to restrict the ability of Iran’s government to develop a nuclear arsenal. It is clear that Obama and his aides have decided that this is the most important foreign policy initiative that they will pursue in his remaining time in office. And they have made clear that they can make no concessions about potentially modifying the agreed-upon plan to make it more acceptable in Congress.

The deal is being offered on a take-it-or-leave-it basis only. And, given the fact that the Republican leaders of both houses oppose the Iran agreement, the President cannot afford significant defections from his Democratic allies.

It thus was to be expected that the White House would react very strongly when officials there learned that the Democratic senator who appears to be next in line to lead that party’s bloc of senators, when a new Congress assembles after next year’s elections, will oppose the Iran deal, and will work for its rejection. That senator is Charles Shumer of New York.

The public reaction so far from those who are close to President Obama was sufficiently strong as to suggest that they would like to see him punished for breaking ranks on this crucial question. If America had a parliamentary system, that kind of party discipline would have considerable chance of succeeding.

But is that something that an American president and his aides want to risk doing, and is it something they can actually bring about?

If they do intend to insert themselves directly into the Democratic caucus, to try to head off Shumer’s leadership candidacy, they risk alienating other Democrats with whom Shumer already has a following. The President, as a former senator himself, almost surely would hesitate before intruding personally or through his lieutenants into caucus consideration of its next leader.

The more limiting factor, though, is that the Iran deal will either succeed or fail in Congress this year, and the leadership issue among Senate Democrats will not reach a serious point until the latter part of next year, at the earliest. At that point, the President will be in his final weeks in office, and lame-duck status tends to diminish the political strength of the White House.

The reality is that the White House’s only realistic option at this point is not to directly threaten the New York senator’s leadership ambitions, but simply to go on waging a public relations effort to keep others in the caucus from following him into the opposition on the Iran pact.