Lyle Denniston, the National Constitution Center’s constitutional literacy adviser, examines the debate over conflicts of interest within the Supreme Court after a recent incident involving stock ownership and a Justice’s spouse.

THE STATEMENTS AT ISSUE:

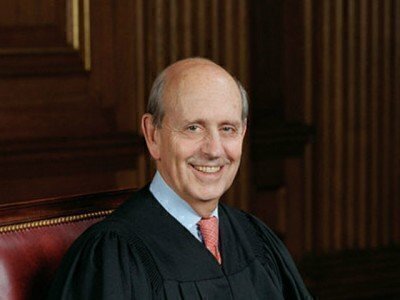

“Justice Stephen Breyer’s oversight [in hearing a case possibly affecting his wife’s stock ownership] shows that the Justices’ current system of self-checking for conflicts [of interest] isn’t working. The three who hold shares of publicly traded companies – Breyer, Samuel Alito and Chief Justice John Roberts – should instead place their securities in blind trusts for the duration of their tenure on the court – and should generally be more vigilant about potential conflicts.”

– Excerpt from a public statement on October 16 by Gabe Roth, executive director of Fix the Court, an advocacy organization that seeks more transparency and accountability in the Supreme Court’s work. He was reacting to Justice Breyer’s belated discovery that his wife owned shares in a company potentially affected by an energy policy case that the court heard on October 14. Soon afterward, that stock was sold.

“The case is the latest example of a recurring phenomenon: a Supreme Court fight proceeding under a cloud because of judicial stock holdings. Recusals and last-minute stock sales are fueling calls for the Justices to shift into investments less likely to pose a conflict of interest, while underscoring the complications that can arise in a system that gives the Justices broad discretion to decide when to step aside.”

– From a news story on October 15 by Greg Stohr of Bloomberg News about the Breyer incident. Stohr’s discovery of the stock ownership led the Justice’s chambers to decide that the stock had to be sold so that Breyer could continue to take part in deciding the energy case.

WE CHECKED THE CONSTITUTION, AND…

Even before the Constitution was drafted in 1787, it was a common practice among the state governments to permit judges to keep their seats on the bench only if they conducted themselves ethically. The Constitution picked up that standard in Article III creating a national court system, giving all federal judges lifetime tenure “during good behavior.”

In promoting ratification of the basic document, Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist Paper No. 78 of the need for judges “who unite the requisite integrity with the requisite knowledge.” He described the “good behavior” mandate as “certainly one of the most valuable of the modern improvements in the practice of government….It is the best expedient which can be devised in any government, to secure a steady, upright, and impartial administration of the laws.”

But how is the public, and how are judges, to know what satisfies a “good behavior” standard? Since 1924, there has been a code of ethics for federal judges, but even today it remains the reality that the Justices of the Supreme Court follow that code only voluntarily (and, despite a popular misconception, that code is actually more advisory than binding on judges on lower federal courts).

Within the Supreme Court, the Justices do not sit in judgment of each other’s ethical conduct. That is a choice left entirely to the individual members, although they sometimes do consult each other about that. Among themselves, though, they retain some doubt that Congress has the authority – without violating the Constitution’s separation-of-powers doctrine – to make an ethical code mandatory for the Supreme Court’s members.

Although within Congress, and among some outside observers, there are regular calls for Congress to compel the Justices to abide by an ethics code, those measures do not get passed, so the system of voluntary ethical restraint continues unaltered.

The process of self-restraint has had an interesting new test. On Wednesday of last week, the Supreme Court held a hearing on an important case on the power of the federal government to regulate the price at which electricity is sold. Justice Samuel A. Alito, Jr., was not on the bench; he had taken himself out of the case, presumably because he owned shares in a company that owned one of the companies directly involved in the case.

As matters would turn out, another Justice, Stephen Breyer, did take part in that hearing, apparently without realizing that his wife owned exactly the same company’s shares as Alito does. Like the others on the court, Breyer has a system of checking in advance whether he has reasons to avoid cases in which he or his wife has a financial interest. That check, this time, did not turn up the conflict that Justice Alito’s system did.

Informed of the conflict, the Breyers promptly arranged for that investment to be sold. At that point, the court would later disclose, the Justice decided for himself that it would not be an ethical violation for him to continue to take part in the energy case as the court moved toward deciding it. That, apparently, was the end of the matter – except, of course, for the public discussion it has stirred up.

The incident may have been unusual, because the very same company’s stock was the source of a conflict of interest, raising issues about whether the internal checking systems are routinely reliable.

But the incident was not at all unusual as a source of potential public dialogue about “good behavior,” and how that is enforced among federal judges. Not so long ago, for example, two Justices’ participation in the same-sex marriage cases was challenged because, before that ruling had been made, both of them had officiated personally at same-sex weddings. Aware of the controversy, the two went ahead and took part in the ruling.

One factor that helps the Justices decide such questions is that, unlike lower court judges, if a Supreme Court’s member steps aside, there can be no replacement. The Supreme Court has nine members, and only the specific nine sitting at any given time. They thus have long felt a “duty to sit,” and generally have decided against sitting when the conflict of interest reaches the point where it really is not debatable.

To some observers, perhaps, right and wrong in judicial behavior is -- or should be -- clear, definite and not a matter of individual choice. To others, ethics is in the eye of the beholder, and is a matter of personal conscience. The Constitution, it seems, does not choose up sides in this debate, mandating only “good behavior,” without further elaboration.